The Norse runes of the Younger Futhark are a mysterious as they are ancient. The fascinating symbols have captured the imagination of scholars, mystics, and poets for centuries and continue to enthrall people today. They came into use around the beginning of the Viking Age and was in use throughout that time.

Why should these symbols continue to hold such power? Is it true that they carry with them some inherent magic? What do the literary sources and contemporary scholars have to say?

If you love Norse runes and want answers to all these questions, read on.

Origins of the runes

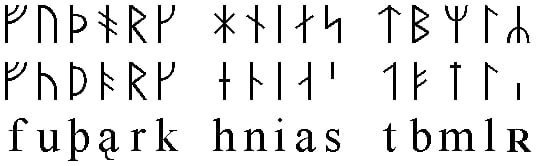

There are two main versions of Norse runes; the Elder Futhark and the Younger Futhark. Early Germanic tribes used the Elder Futhark system from around the beginning of the Common Era. This continued until about the 8th century. The Younger Futhark, also known as Scandinavian runes, date from about the 9th century.

There are two main ways to approach the subject of Norse runes. One is via traditional lore, the other through modern archaeology. They are not, however, mutually exclusive. Viking thought was not as linear as some historians and even many pagans would like it to be.

The accepted historical account, agreed upon by modern scholars is that the runes derive from the Greek alphabet. Observed similarities between several of the characters make this abundantly clear.

The Younger Futhark Norse runes

Widespread use of the Younger Futhark begins in approximately the 9th century. Its adoption is loosely contemporaneous with the Viking age. The alphabet found its final form after a transition period of approximately 200 years in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Germanic Elder Futhark as we have seen has a total of 24 characters and derives from the Greek alphabet. The Younger Futhark is reduced to 16 characters even though at the time Norse was developing more phonemes in the spoken language.

This smaller version of the ancient alphabet is further subdivided into Danish and Swedish/Norwegian versions known respectively as the long-branch and short-twig runes. The final incarnation of the alphabet happens in the 10th century when vertical strokes are all but abandoned in the ‘staveless’ version.

Why the Norse community chose to drop 8 characters from their alphabet during a time of increasing linguistic complexity is something of a mystery. The resulting alphabet left its users with fewer letters to represent more sounds.

The change didn’t happen overnight. There is an overlapping period between approximately 650 to 800 CE when we find inscriptions in both Futhark alphabets side by side. This may indicate parallel use across generations or conflicting views among older traditionalists and younger progressives.

Name and Symbol of the Younger Futhark Runes

Both Futhark alphabets get their name from the first six letters listed in each. These are as follows:

ᚠᚢᚦᚬᚱᚴ pronounced fé úr Thurs As reið and kaun. Together these spell ‘Futhark’.

When comparing the Younger futhark with the Elder futhark, most of the runes stayed unchanged. Only a handful of the runes actually changed as the as the Scandinavian, or Norse runes (Younger futhark) evolved from the Elder futhark. On the way they went from 24 runes to only 16, of which were new.

Evolution from Elder to younger futhark

From the first aett in the Elder futhark, the a rune changed its appearance and went from being associated with the a sound, to an Old Norse ą. Furthermore, the old g and w runes disappeared.

In what was the second aett in the Elder futhark, the h, and s runes are new and the æ and p runes disappeared. The old j rune was also lost, but in its place came the new *nauðr rune which now represents the a sound in the Norse runes. The same happened to the old z rune which diseappears. In its place, but moved to the end of the 16 Norse runes is the new *yr rune, representing r.

The theird aett in the Elder futhark possibly went through the largest change, losing four of its original eight runes. The e, ŋ, o and d runes are lost, while the t, b and l runes remains the same. The only “update” being the m rune changing in appearance.

| Rune | Name | Meaning / Association |

| ᚠ | fé | cattle, money, wealth |

| ᚢ | úr | iron, rain, slag |

| ᚦ | Thurs | name for a male jötunn |

| ᚬ (new) | As/Oss | god |

| ᚱ | reið | ride |

| ᚴ | kaun | ulcer |

| ᚼ (new) | hagall | hail |

| ᚾ/ᚿ | nauðr | need |

| ᛁ | ísa/íss | ice |

| ᛅ/ᛆ (new) | ár | year, plenty |

| ᛋ/ᛌ (new) | sól | Sun |

| ᛏ/ᛐ | Týr | the god Tyr |

| ᛒ | björk | birch |

| ᛘ | maðr | man, human |

| ᛚ | lögr | sea |

| ᛦ (new) | yr | yew |

It is easy to see from this how modern enthusiasts of Norse culture might assign specific magical qualities to each symbol. The characters themselves have an attractive angularity possibly due to their primary use as stone carvings.

The Futhark Runes: a magical alphabet?

The very first letter, ᚠ fé or ‘wealth’ might be a nice symbol to carve into the main lintel of your household, or keep stowed in your wallet. But there is little evidence that anything like this ever happened in Viking times.

A glance at the first letter would suggest that those following will have similar meanings related to good fortune, childbirth, health, or victory in battle. The actual meanings, however, are disparate and lack any cohesive theme.

Of what use would the character ᚴkaun ‘ulcer’ be to its user? If it was to protect against having an ulcer or to cause your enemy to have one, why this one ailment only and none other?

Why are there only two trees present, the yew and the birch out of so many kinds that must have been known to the farming, and forest-dwelling people of ancient and medieval Scandinavia?

Traditional origins of the Norse runes

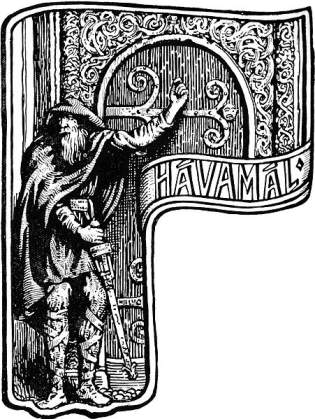

Despite the skepticism of some scholars, the words of Odin as described to us in the Hávamál, a collection of wise sayings, tell a very different and vivid story. The Rúnatal section in the poem goes into some detail on the subject.

Stanzas 139 to 146 of the Hávamál describe how the Allfather came to his knowledge of the alphabet and give some explicit indications as to their use.

- I counsel thee, etc. Wherever thou beer drinkest, invoke to thee the power of earth; for earth is good against drink, fire for distempers, the oak for constipation, a corn-ear for sorcery, a hall for domestic strife. In bitter hates invoke the moon; the biter for bite-injuries is good; but runes against calamity; fluid let earth absorb.

His admonition to use ‘runes against calamity’ suggest something more potent than a mere alphabet. We can speculate that the ability to write perhaps added power to magical incantations. A spell committed to a runic inscription may be more effective than a solely verbal invocation.

There is, however, no evidence of this having ever occurred historically in Norse communities.

The runes described in Havamal

In the traditional version, Odin sees the power of runes as so important that he subjects himself willingly to a prolonged ordeal to gain their knowledge.

- I know that I hung, on a wind-rocked tree, nine whole nights, with a spear wounded, and to Odin offered, myself to myself; on that tree, of which no one knows from what root it springs.

- Bread no one gave me, nor a horn of drink, downward I peered, to runes applied myself, wailing learnt them, then fell down thence.

Nine nights, and presumably nine days, the King of the Aesir hung, wounded on a branch of the world tree Yggdrasil. Windswept and thirsty, wailing continuously in order to learn the characters we presume, of the Elder Futhark alphabet.

Is this not an excessive amount of pain and effort for the most powerful of all the gods to go through to learn random symbols with which to represent the spoken word?

If the form of the letters hold no meaning, couldn’t Odin have taken any collection of letters and simply created his own alphabet? Instead, he peered down from the tree, applying himself assiduously for nine whole days in order to learn these specific characters.

Stanza 144 and 146 of Havamal:

144. Runes thou wilt find, and explained characters, very large characters, very potent characters, which the great speaker depicted, and the high powers formed, and the powers’ prince graved:

The words ‘very potent characters’ suggests again that the letters themselves held power beyond the words they form.

And finally, in stanza 146, the last of the Rúnatal section of the Hávamál, Odin asks the following series of challenging questions:

146. Knowest thou how to grave them? knowest thou how to expound them? knowest thou how to depict them? knowest thou how to prove them? knowest thou how to pray? knowest thou how to offer? knowest thou how to send? knowest thou how to consume?

It would be easy to infer here that the followers of Odin used the runes to do all of the above and that without them, effective prayer or offerings might not be possible at all.

Power of the written word

Perhaps in a world of low literacy, the simple act of knowing an alphabet and how to form words was, in a way, an act of magic. A wise man or woman reading words from a rune stone might seem to be conjuring meaning from the earth itself.

Whoever the writer of the Hávamál was, it seems that they considered the runes to be of great magical value in and of themselves. The question is, how old and how ‘authentic’ is this document? Does it represent true Norse belief or the beliefs that later Icelandic people held about their ancestors?

Widespread Use of the Younger Futhark Norse runes

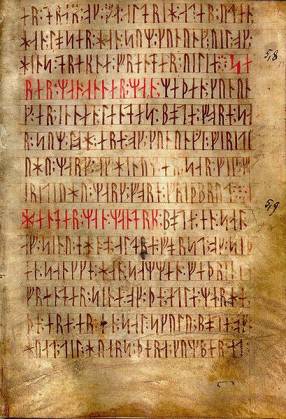

To date there have been found more than 3000 Norse rune stone inscriptions in the 16-character version and many are casual in nature suggesting a very different attitude to literacy than in earlier times.

Some archeological finds include magical inscriptions, but these are independent of the individual meanings of the letters. They call upon the powers of the gods to intercede and ask for their help as would be the case in a simple prayer in any other alphabet.

The use of runes persisted well into the Christian age of Scandinavia and in fact, many runic inscriptions have Christian references. This leads us to believe that Norse Christians did not associate their indigenous alphabet with pagan magic. If they had, it is unlikely they would have continued to use it.

This is not to say however, that earlier Norse communities didn’t assign magical use to them. Possibly in more ancient times only elite members knew the alphabet and used it exclusively for ritual purposes. There are some inscriptions where runes are used repeatedly without obvious meaning.

This might indicate that a specific character was being used to magical effect, but the meaning has not been recorded. As the old ways died out and were supplanted by Christianity, an oral magical tradition may have been lost to history. For the moment at least, we are lacking hard evidence either way.

Other literary sources

In the Brynhildarljóð also known as the Sigrdrífumál in the Poetic Edda, the valkyrie Brynhildr/Sigrdrífa (victory driver) gives detailed advice to the hero Sigurd about the magical use of the runes.

The Poetic Edda was written down in the 1270s but the actual date of composition of the text is more difficult to determine. The content, however, is almost entirely unique in that it contains a prayer to the gods from a Valkyrie.

Brynhildrs’ prayer for Sigurd

Stanzas 5 to 19 contain the main body of her explanation of runic magic and hold great potential insight for both the scholar and the modern pagan.

In stanza 5 Sigrdrífa/Brynhildr brings beer to the hero which she informs him has been highly charged with rune magic.

Beer I bring thee, tree of battle,

Mingled of strength and mighty fame;

Charms it holds and healing signs,

Spells full good, and gladness-runes.

What exactly is a gladness rune and how would it be applied to beer?

In stanza 6 she counsels him to inscribe a rune onto his battle sword with explicit reference to ᛏ/ ᛐor Týr, patron god of warriors.

Victory runes you must know

if you will have victory,

and carve them on the sword’s hilt,

some on the grasp

and some on the inlay,

and name Tyr twice.

The instructions are quite clear. For victory in battle the name of the god Týr, embodied in the runic character named for him, should be carved twice into the hilt of a warrior’s battle sword.

This otherwise meaningless repetition of a rune on an object mirrors other scattered inscriptions that seem to be repetitive or possibly ritualistic in nature.

Was this a later invention of the medieval Norse mind? Or is this a remnant of real runic magic from Viking times?

practical Use of the Old Norse ale-runes

Further stanzas list other uses for Ølrunar or ‘ale-runes’ including the following:

- Biargrunar, ‘birth-runes’

- Brimrunar, ‘wave-runes’

- Limrunar, ‘branch-runes’

- Malrunar, ‘speech-runes’

- Hugrunar, ‘thought-runes’

It would appear that in the 13th century at least, there was an idea that the ancient Norse used runic magic for very practical reasons, and in very specific ways.

Stanzas 13 to 14 give a version of Odin’s quest for the runes and the valkyrie’s concern with the topic continues through stanzas 18 and 19.

18. Shaved off were the runes that of old were written,

And mixed with the holy mead, And sent on ways so wide;

So the gods had them, so the elves got them,

And some for the Wanes so wise, And some for mortal men.

19. Beech-runes are there, birth-runes are there,

And all the runes of ale. (And the magic runes of might;)

Who knows them rightly and reads them true,

Has them himself to help;

(Ever they aid, till the gods are gone.)

This valkyrie at least knows that there are multiple categories of runes. From the original wisdom alphabet gleaned by the Allfather, some are reserved for the Aesir, some for light elves, some for the Vanir, and some for the mortals of Midgard.

If accepting the Poetic Edda as evidence, we have it on good authority from Sigrdrífa herself, a valkyrie no less, that the runes are magical and used specifically for that purpose.

This is not scholarly evidence by any means, but an intriguing possibility nonetheless.

Magical archeology

There are some finds however, that show clear indications of magical usage. Three isolated incidences occur but each gives a very clear, vivid picture of runes used with specific magical purposes. Two involve amulets and all three are related to healing.

The first is an amulet which dates to the 1000s and was found in Sweden. The object holds a carving of a fish and a prayer to Thor to strike down the entity that is causing illness. It asks for the protection of gods over and under the bearer to ward off further illness.

The second is a runic charm in the margins of an English manuscript dating from 1073 and again asks for Thor’s help to ward off ‘vein danger’. The rest of the manuscript is not in the runic alphabet and has no relation to magic or healing.

The third is another Swedish amulet that again invokes Thor to heal a wound, this time with the help of healing herbs.

The runes here might be seen as being used with clear magical goals. However, it is not evident that they are being used as anything other than an alphabet with which to articulate and record an intention.

Bind runes

Another category of magical usage includes bind runes. The name would suggest ‘binding’ spells. However, the true meaning is more mundane and it simply means cursive text, ancient Norse style.

Any two or more runes joined together are a bind rune. However, scholars see no reason this was to achieve anything other than to look attractive and save space.

The Bratsberg Brooch holds an inscription in Elder Futhark. Its meaning is not entirely clear but may mean ‘I, rune-master’. To say the intention was certainly magical or definitively prosaic would be a presumption either way. The two words are each inscribed as bind runes.

There are other examples, including the Thor Bless Runes which are unusual in that they are Younger Futhark. The inscription on the gravestone simply says those three words and each is written as a bind rune.

FAQs about Younger Futhark Norse Runes

Elder Futhark comes from an earlier period and has 24 characters. Younger Futhark is an evolution of the Elder version and holds only 16 characters.

There is no archeological evidence that they are magical symbols. Eddic literature, however, describes them as having immense power and being used for magical purposes.

Historically it is thought that they come from the Greek alphabet with additions from intermediary cultures and some indigenous innovations. Mythologically they are a gift from Odin. The Allfather hung for 9 nights on a branch of the world tree to learn their use.

The Vikings practiced magic with runes. There is no conclusive evidence that they used the runes as individual power symbols for magical purposes.