Ravens, if you have never seen one, are large, ominous-looking black birds. With strong talons and a beak capable of ripping flesh off a corpse, they are imposing to behold. In Norse mythology, Huginn and Muninn are the two ravens of Odin the Allfather, always by his side, even in battle.

Odin’s Ravens

Not merely perched by Odin’s shoulders, I believe it’s fair to say that Huginn and Muninn are fylgjur of Odin. Acting as extensions of Odin himself, they were his eyes and ears across the nine realms.

The fylgja (plural fylgjur) is the concept of the companion spirit, often in animal form, following you through life. The Norse believed everyone could have them, but at least for humans, they were mostly spirits. For Odin, arguably the most powerful Seidr shaman of Norse mythology, it seems only natural he would have fylgjur with him.

Acting as Odin’s eyes and ears, Huginn and Muninn would travel the nine realms every morning, gathering information for him. When riding into battle, they would also go with him, just like his wolves Geri and Freki followed him.

However, different from Sleipnir for example, they were much more than just animals associated with Odin, they represented him. When seen on a battlefield, ravens were seen as there on behalf of Odin or being him in raven form.

Odin was so closely associated with his ravens that one of his many names was actually Hrafnagud, Raven God. This is found in the Gylfaginning, part of Snorri’s Prose Edda.

Huginn and Muninn meaning

Huginn (sometimes Hugin) is derived from the Old Norse “hugr”, which comes from the Proto-Germanic “hugiz”, meaning “thought”. The translation however is not as straightforward and the meaning can represent a spirit or even a sense of something.

In later, more modern times I believe the word “hug”, as in giving someone a hug is also derived from the same source. In older Norwegian, “hug/hugen” comes from “hugr” and can be understood as both soul and something independent of the body.

According to Norwegian folklore, some people were believed to be able to hurt others from afar, with their “evil hugen”. While this was in Christian times, there are many examples of Old Norse myths making it into modern folklore people believed in hundreds of years later.

Muninn (sometimes Munin) is derived from the Old Norse “munr”, which comes from the Proto-Germanic “muniz”, which can be seen as meaning “memory”. Just like how Huginn means much more than thought, however, the meaning of Muninn is much broader than just “memory”.

The old Norse “munr” could as well be understood to mean mind, joy or pleasure, delight found in one’s mind. Like so many old Norse words or concepts, the understanding is often contextual and often not a simple word.

Considering the meaning and looking at the old Norse hugr and munr, you could argue they mean almost the same. Both words, and as such Huginn and Muninn, are connected to the mind and seen as separate from the body. Free to travel the nine worlds, seeking out information and knowledge.

Huginn and Muninn in Norse myths and poetry

While they never play a major part in any of the old myths, Huginn and Muninn are always with Odin. As his companions, or as discussed above, extensions of him, they go where Odin goes. It is believed that even in the end, at Ragnarok, they will be there by his side. The mystisism associated with ravens live strong in Scandinavia to this day, for example there is a portal of all funeral homes in Norway called Ravnen (raven).

Poetic Edda – Grimnismal

The Grimnismal poem is from the Poetic Edda and tells the story of a time Odin was held captive. The only one willing to bring something to drink to Odin, was Agnar the young son of the king. Odin, who was in disguise (naturally) and calling himself Grimnir, shared his knowledge with the young boy.

In verse twenty, he tells of his ravens, and how they fly across the worlds. However, it isn’t clear from this verse what the purpose of their flying every day actually is.

Huginn and Muninn, | each day fly

Over the earth;

I fear for Hugin | that he will be lost,

But I fear more for Munin.

Who are Huginn and Muninn to Odin?

A lot has been made of this by scholars in the last hundred years or so, maybe longer back even. Is Odin just saying he is worried his ravens won’t make it back or are they representing something else to him?

As I noted already, their names mean Thought and Memory, both invaluable to someone as knowledgeable as Odin. Ever since Odin first learned about Ragnarok and the prophesied doom of the gods he has tried to reverse fate.

If we assume Huginn and Muninn not only have magical abilities, but are extensions of Odin, losing one of them might be akin to losing his mind, or memory. Both an intellectual Odin, with no memory, or a mindless, but all-knowing Odin would be disastrous to his future.

Just what they are to Odin, and how they act on his behalf differs depending on what we perceive Huginn and Muninn to be. If they are fylgjur to Odin, they are akin to spirits in raven form who follow and help him.

However, they might be closer to the personifications of Odin, created by his shamanic powers. If so, he could send out his thoughts and memories across the lands to learn all there is to learn out there.

One of Odin’s names is Hrafnagud (Raven God) which might be a good indication of his close association with ravens.

Prose Edda – Gylfaginning

When Snorri Sturluson wrote the Prose Edda, he based it largely on information he found in the collection of poems called the Poetic Edda. In the part called Gylfaginning, chapter 38 he quotes Grimnismal (see above) when describing Huginn and Muninn.

Gylfaginning Chapter 38

Two ravens sit on Odin’s shoulders, and bring to his ears all that they hear and see. Their names are Hugin and Munin. At dawn he sends them out to fly over the whole world, and they come back at breakfast time. Thus he gets information about many things, and hence he is called Rafnagud (raven-god).

As is here said:

Hugin and Munin

Fly every day

Over the great earth.

I fear for Hugin

That he may not return,

Yet more am I anxious for Munin.

According to Snorri then, we know that Odin himself sends out the ravens every morning in order to learn more. As is the case with much of the knowledge we have about Norse mythology, it was written down late. Having been shared orally for hundreds of years it was finally put down on paper in the 12th and 13th centuries. It could of course have been written down before, but the archeological record is scarce.

So often, things might be stated that would require a broader knowledge than offered in a particular poem. It would safely be assumed that most of the listeners knew the story being told and other supporting stories quite well.

Prose Edda – Skaldskaparmal

In Skaldskaparmal, the second part of the Prose Edda, Snorri lays out almost a thesaurus for skaldic poets. Among other lists of names and kennings, in chapter 75 we find a list of names for ravens and eagles. The chapter is longer than what I am including below as I cut it before it starts on eagles.

Reading these lines I almost feel transported back in time. Large grassy plain, huge oak tree with black ravens sitting in it, looking out on a battlefield. Patiently waiting for the fighting to subside, so that they can drink the blood and rip the flesh off the fallen warriors.

“Heiti of the raven and the eagle“

Two are those birds which there is no need to periphrase otherwise than by calling blood and corpses their Drink and Meat: these are the raven and the eagle. All other male birds may be paraphrased in metaphors of blood or corpses; then their names are terms of the eagle or the raven.

As Thjódólfr sang:

The Prince with Eagle’s Barley

Doth feed the bloody moor-fowl:

The Hörd-King bears the sickle

Of Odin to the gory Swan’s crop;

The Sater of the Vulture

Of the Eagle’s Sea of corpses

Stakes each shoal to the southward

Which he wards, with the spear-point.

These are the names of the raven: Crow, Huginn, Muninn, Bold of Mood, Yearly Flier, Year-Teller, Flesh-Boder.

Thus sang Einarr Tinkling-Scale:

With flesh the Host-Convoker

Filled the feathered ravens:

The raven, when spears were screaming,

With the she-wolf’s prey was sated.

Thus sang Einarr Skúlason:

He who gluts the Gull of Hatred,

Our precious lord, could govern

The sword; the hurtful raven

Of Huginn’s corpse-load eateth.

And as he sang further:

But the King’s heart swelled,

His spirit flushed with battle,

Where heroes shrink; dark Muninn

Drinks blood from out the wounds.

Fragment of poem by Óláfr hvítaskáld Þórðarson quoted in Skáldskaparmál

In the Skaldskaparmal Snorri quotes a number of skalds, one of which was Óláfr hvítaskáld Þórðarson. Olafr “Hvitaskald” Thordarson was an Icelandic skald who lived from the early to mid 13th century.

The fragment of a verse as seen below describes how Huginn and Muninn accompany Odin when he communicates with the newly dead.

Old Norse: “Tveir hrafnar flugu af ǫxlum Hnikars; Huginn til hanga, en Muninn á hræ.”

“Two ravens flew from Hnikarr’s (one of Odin’s many names) shoulders; Huginn to the hanged one, and Muninn to the corpse.”

It might help to bear in mind that Odin in Hávamál shares that he knows of a spell to make the dead speak again. Much as he raises the völva in Völuspa from the dead to gain her knowledge.

From the partial poetic verse above, it might seem that the actual conduits of this communication with the dead are Huginn and Muninn.

It’s difficult to know how much stock to put in this short part of a poem. However, if we explore the possible meaning of this, we can gain more insight into how Huginn and Muninn were able to gain all their knowledge.

The Vikings did believe that the dead held special knowledge only accessible to the departed. This is also found in the different stories that surround the various undead in the Norse myths. Be it the haugbui or the draugr, they had knowledge and powers beyond that of the living.

As such, it might be that Huginn and Muninn not only had the ability to fly all over the worlds and to speak, but specifically also speak with the dead.

Play Fun Norse Quiz

Is this article making you even more curious about Norse gods and goddesses? You can satisfy your curiosity by playing a fun Norse mythology quiz. This way, you can test your knowledge about Norse gods and goddesses, as well as fill in some gaps. Good luck and have fun playing!

Don’t forget to try our other games as well!

Huginn and Muninn in archeological finds

Ravens, just as most of the Norse gods, were attested to long before the time we know as the Viking age. Their connection with Odin, or Wodan, has been seen in many archeological finds. Some are dating a few hundred years even before the Viking age got going.

Below I’ve collected a few interesting ones, but ravens (or possibly eagles) have been found on all kinds of different artifacts. While we don’t find many mentions of ravens in manuscripts, they seem to have been important symbols in everyday life.

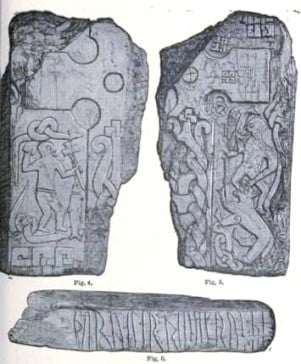

Thorwald’s Cross on the Isle of Man

Set in the Irish sea between England, Wales and Ireland the Isle of Man is small but strategically placed. Vikings came to the island at the end of the 8th century and had conquered the island by 820. Adopting the old Celtic tradition of raising stone crosses, the Vikings left a number of stone crosses with runic inscriptions.

One such stone cross is known as the “Thorwald’s Cross” and is found in the Kirk Andreas church. The church is from the early eighteen hundreds but is probably built on the spot of an ancient Christian church. In the church, they have several stone slab crosses of Norse and Viking origins.

On Thorwald’s Cross, we see a man holding a spear and a large bird on his shoulder fighting with a large wolf-like beast which is biting his leg. Believed to be depicting Odin with his spear Gungnir and with Huginn or Muninn on his shoulder.

Gold Bracteates depicting ravens

Likely inspired by Roman and Byzantine production of artistic gold medallions, gold bracteates are small, richly decorated round pendants. Popular in the Norse Iron-age and onwards, there have been many finds and quite a few with raven motifs.

Two such bracteates were found in Tjurkö in Sweden in 1817 when a farmer was clearing a field for growing crops. Found among rocks in the topsoil, the two bracteates had likely been lying there for more than a thousand years. They are dated to somewhere around 400-600 AD which also shows how the Norse gods predate the Vikings by centuries.

The second one depicted below is from a collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC.

This is also dated to around 400-600 AD and was found somewhere in Scandinavia.

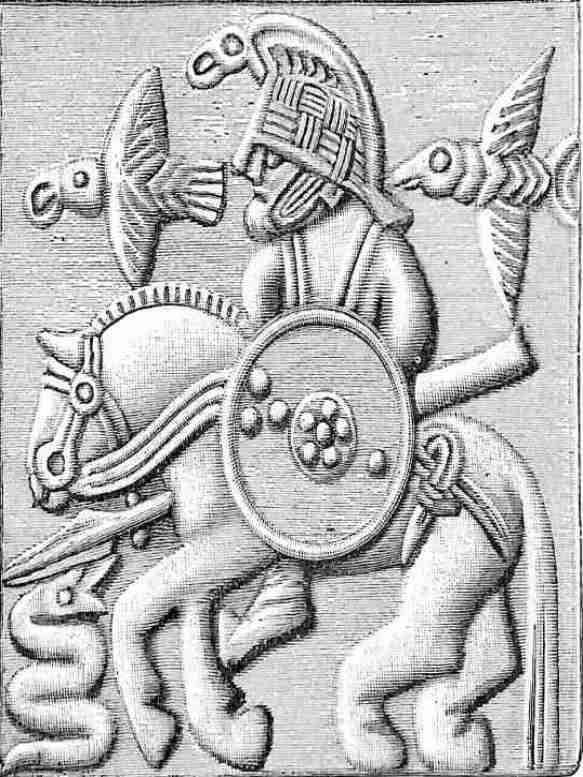

Decorative bronze plates from Iron-age helmet

In 1881 remains from several Iron-age boat burials were found in the Vendel area of Sweden. Most of the graves had been plundered, however a few had been left intact. In one of those a helmet was found that when it was in use had decorative bronze plates attached.

One of these bronze plates has a motif of a man on a horse. He is holding a spear and two large birds are flying along with him. Also worth noticing is the nose guard on the helmet, shaped like a raven.

The symbolism of ravens

Ravens have fascinated people for millennia and across many cultures. They are mentioned several times in the bible, for example, when “Noah sent forth a raven…” to find land after forty days. But cultures as far away as Native Americans on the west coast of North America also held the raven in special regard.

It should be no surprise really then that ravens made it into Norse mythology as well. They were a sign of Odin’s presence if an offering was made, or when seen close to a battlefield. Marshaling the good luck the raven could bring and maybe also scaring their enemies, several Viking earls and kings flew the raven banner.

The Raven banner

Not much is known about the so-called raven banner, but we do know it was a Viking-age flag. However we do not really know how widely used it was, and it is barely mentioned in old Norse manuscripts.

One place where the raven banner plays an interesting role however is in the story of Sigurd Hlodvirsson. Also known as Sigurd the Stout, he was an Earl of Orkney from around 980 till his death in 1014.

Earl Sigurd the Stout and the magical raven banner

Coming to the aid of then king of Dublin, Sigtrygg Silkbeard, Sigurd fought at the Battle of Clontarf. According to the Orkneyinga Saga, Sigurds Irish mother Audna was a strong sorceress and she made him a raven banner. However, the banner’s magical properties led to Sigurds ultimate death, and is described in chapter eleven in the saga.

“His raven-banner, which was borne before him, was fulfilling the destiny announced by Audna, when she gave it to him at Skida Myre, that it would always bring victory to those before whom it was borne, but death to him who bore it. Twice had the banner-bearer fallen, and Earl Sigurd called on Thorstein, son of Hall of the Side, next to bear the banner. Thorstein was about to lift it, when Asmund the White called out, “Don’t bear the banner, for all they who bear it get their death.” “Hrafn the Red!” cried Earl Sigurd, “bear thou the banner.” “Bear thine own devil thyself,” said Hrafn.[29] Then said the earl, “’Tis fittest that the beggar should bear the bag,” and with that he took up the banner, and was immediately pierced through with a spear. Then flight broke out through all the host.”

Featured Image Credit: Ranveig, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fulfilling his mothers prophecy, the banner helped Sigurd in many battles until his own death, maybe paying the ultimate price. Possibly depicting that very banner is a part of the Bayeux Tapestry as seen below.