When we delve into all the gods of Norse mythology, Odin, the Allfather, stands out as a complex and multifaceted figure. Both revered and feared, he embodies the quintessence of a god with deep ties to the cosmos, wisdom, and the human experience. While he and his brothers Vili and Ve created humans and our world, he was not exactly a guardian of mankind.

While I have tried to keep this short and have made the choice to drop some mentions in myths and ancient texts etc. it has proven to be a long post. I do hope you find this enlightening and interesting. If you are curious, please do explore further in some of the many poems listed in the “Mentions…” chapter.

Odin Key Facts

| Parents | Borr and Bestla |

| Partners | Frigg ( wife) Rindr (co-wife) Grid (co-wife) |

| Siblings | Vili and Vé |

| Offspring | Thor, Balder, Váli, Vidar, and others |

| Tribe | Aesir |

| Old Norse name | Óðinn |

| Other names | Woden, Wotan |

| The God of | War, Death, Poetry, Wisdom, and Magic |

| Ass. Animal | Ravens (Huginn and Muninn), Wolves (Freki and Geri) and Sleipnir |

Name and Etymology

Odin, pronounced as /ˈoʊdɪn/, finds its origins from the Old Norse theonym Óðinn. Evident from the runic inscription “ᚢᚦᛁᚾ” on the Ribe skull fragment, this name has rich historical connections and nuances. Even today, this name is regularly included in lists of best Viking names for boys. This theonym is closely related to several medieval Germanic names. From Old English, we have “Wōden”, in Old Saxon it’s “Wōdan”, “Wuodan” in Old Dutch, and “Wuotan” or “Wûtan” in Old High German and Old Bavarian respectively. Tracing it further back, they all share roots with the reconstructed Proto-Germanic masculine theonym *Wōðanaz (or alternatively *Wōdunaz).

When we dissect the meaning of *Wōðanaz, it can be translated as the ‘lord of frenzy’ or ‘leader of the possessed’. This interpretation is borne out of the Proto-Germanic adjective *wōðaz, which conveys a sense of being ‘possessed’, ‘inspired’, ‘delirious’, or ‘raging’. This base term is then coupled with the suffix *-naz, signifying ‘master of’. A deeper look at internal and comparative evidence related to *Wōðanaz strongly suggests a divine theme centered on possession or inspiration, indicative of an ecstatic or prophetic state of divination.

Odin and Óðr: Similar Meaning and Possibly Closely Related

Philologist Jan de Vries puts forth an intriguing perspective regarding the relationship between the Old Norse deities Óðinn and Óðr. According to de Vries, there’s a high probability that the two were initially intertwined, as seen in the dual naming convention of Ullr–Ullinn. The elder form, Óðr (*wōðaz), is theorized to be the foundational source of the name Óðinn (*wōða-naz). This suggests a nuanced evolution of these deity names, underscoring the rich tapestry of Norse mythology.

Norse Mythology Evolved Over Centuries

There is a common belief among many scholars that Odr is just another name for Odin. While I follow the arguments made, I tend to think of them as two different individuals. Along the same line of arguments, Freyja is another form/name of Frigg, and Njord used to be Nerthus, a more ancient Germanic goddess.

Beliefs and understood truths about the Norse gods had been evolving for hundreds of years before the Viking Age. Moreover, they continued to do so long after, and then much of what we now “know” was collected and written down a couple of hundred years after the end of the Viking Age.

Ancient roots: Odin in Roman Records

Even as we trace back to Roman times, we discover mentions of Odin, as well as Thor and Tyr. Tacitus, a notable Roman senator, sheds light on this in his ethnography, “Germania”. In it, he writes:

“Among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship. They regard it as a religious duty to sacrifice to him, on fixed days, human as well as other sacrificial victims. Hercules and Mars they appease by animal offerings of the permitted kind. Part of the Suebi sacrifice to Isis as well.”

In interpreting this passage, scholars have deduced that the deities Tacitus refers to correspond to figures from Norse mythology. Specifically, Mercury is believed to be a reference to *Wōđanaz, who we know today as Odin. Similarly, Hercules corresponds to *Þunraz or Thor, and Mars is linked to *Tīwaz or Tyr. This ancient connection underscores the reach and resonance of these gods, transcending cultures and standing as a testament to their enduring significance in human history.

Kennings and Names for Odin

Kennings are unique to Old Norse and Old English poetry. They are essentially metaphorical phrases or compound words used to describe an object or person in an indirect manner. Instead of straightforwardly naming the object, kennings provide a more poetic, often vivid depiction. When considering Odin, numerous kennings have been used throughout history to capture the essence of this multifaceted god, reflecting his diverse roles and attributes in Norse mythology.

Kennings

| Old Norse Name | Kenning/Name for Odin |

| farmr galga | The burden of the gallows |

| valtýr | The slaughter-god |

| skjaldblœtr niðr ása | The shield-worshipped kinsman of the Æsir |

| böðvar-Týr | The battle-Týr |

| geir-Týr | The spear-Týr |

| Váfuðr Gungnis | The swinger of Gungnir |

| aldafaðir | Mankind’s father |

| hjalmfaldinn snytrir hapta | The helmet-capped instructor of the divine powers |

| hrafnÁss | The raven-god |

| þekkiligr dróttinn foldar | The gracious lord of the earth |

| Grímnir hanga | The Grímnir of hanged ones |

| inum eineygja faðmbyggvir Friggjar | The one-eyed embrace-occupier of Frigg |

| Gautatýr | The god of the Gautar |

| faðir Baldrs | The father of Baldr |

| bági úlfs | The wolf’s enemy |

| vinr Míms | Mímir’s friend |

| farmǫgnuðr | The travel-furtherer |

| vinr Lóðurs | The friend of Lóðurr |

| farmatýr | The god of cargoes |

| bróðir Vilja | The brother of Vili |

| vinr skatna | The friend of warriors |

| hertýr | The army-god |

| vinr Lopts | The friend of Loptr |

| sonr Bestlu | The son of Bestla |

| dolgband | The battle-god |

| beiðir hapta | The ruler of the gods |

| sigtýr | The victory-god |

| víg-Freyr | The battle-Freyr |

| vinr Míms | The friend of Mímr |

| burr Bors | The son of Borr |

| arfi Búra | The heir of Búri |

| vitnis váði | The threat of the wolf |

| bǫðgœðir | The battle-promoter |

| hrafnÁss | The raven-god |

| gramr hliðskjalfar | The lord of hliðskjálf |

| Hildar hjaldrgegnir | The promoter of the noise of Hildr |

| kynfróðs hrafnfreistuðr | The kin-wise raven-tester |

| svinnum sigrunnr | The wise victory-tree |

| haftr sóknar | The god of battle |

| hangagoð | The god of the hanged |

| bani Randvés | The killer of Randvér |

| niðr Bors | The son of Borr |

| vári vagna | The protector of wagons |

| hjaldrgoð | The battle-god |

| spjalli Gauta | The confidant of the Gautar |

| ræsir rógs | The instigator of discord |

| Dvalinn hanga | The Dvalinn of the hanged ones |

| valkjósandi | The chooser of the slain |

| niðr B*estlu | The descendant of Bestla |

| valdr gálga | The ruler of the gallows |

| fallheyjaðr | The death-deployer |

| ræsir rógs | The instigator of discord |

Odin’s Many Names: Insights from Grimnismál

Odin is a multifaceted deity with countless attributes, stories, and, notably, names. In the poem “Grimnismál,” found within the Poetic Edda, we are introduced to a vast array of monikers. In this poem, Odin, disguised as Grimnir, converses with Agnar, a young prince, sharing wisdom about the cosmos. It’s within this dialogue that Odin reveals many of the names he’s been known by across various contexts and adventures. This array of identities offers a richer understanding of his expansive nature and influence in the Norse myths. This is from stanzas 46-50 from the Gímnismál.

46. Grimnir is my name, I am Gangleri, Herjan and Hjálmberi, Thekk and Thridi, Thund and Ud, Helblindi and Hár.

47. Sath and Svipal, and Sanngetal, Herteit and Hnikar, Bileyg, Baleyg, Bölverk, Fjölnir, Grim and Grimnir, Glapsvith, Fjölsvith.

48. Sithhott, Sithskegg, Sigfather, Hnikuth, Allfather, Valfather, Atrid, Farmatyr; Just one name have I never had Since first I traveled among men.

49. I am called Grimnir at Geirröd’s, And Jalk at Ásmundar, And I was Kjalar, when sleigh riding, Thror at the council, Vithur when going into battle; Oski and Omi, Jafnhor and Bilfindi, Gondlir and Harbard amongst gods.

50. I was Svithur and Svidir at Sökkmimir’s, And I tricked the ancient jötun; Son of Mithvitnir, the famous, I slayed single handed.

These are in fact but a few of Odin’s many names, I believe there are around, or just over one hundred all counted.

Odin’s Origins: From Aesir Ancestry to World Creation

Odin is not merely the rules of the gods in Norse mythology; he is intricately linked to the beginning of the cosmos and the lineage of the Aesir. This chain of events starts with the appearance of Odin’s grandfather, Búri. Emerging from the rime ice as it melted from the fiery breath of Muspelheim, Búri was the first of the Aesir. As the cosmos began to take shape, Búri shared this nascent world with the primordial beings Ymir, the first of the frost giants, and Audhumla, the cosmic cow whose milk nourished Ymir.

From Búri came a son, Borr. Borr, with his jötun wife Bestla, fathered three sons: Odin and his brothers, Vili and Ve. These siblings played a pivotal role in shaping the Norse world as we know it. In a cataclysmic event that reshaped the very fabric of existence, the trio confronted and ultimately slew Ymir. Using the body of the fallen giant, they constructed the world: his blood became the oceans, his bones the mountains, his flesh the soil, and his skull the sky. This act of creation, though violent, was necessary to pave the way for the world of gods, mortals, and all the beings in between.

Thus, Odin’s legacy isn’t just as a wise and war-loving deity; his very existence is intertwined with the birth and structure of the universe.

Odin’s Family and Relationships

Odin, the Allfather, wasn’t just known for his wisdom and leadership; his personal life was also a web of intricate relationships. From numerous affairs to several co-wives, and then Frigg as his chief wife, Odin’s familial ties added layers to the Norse tales.

In the Edda’s there are four others besides Frigg mentioned as co-wives of Odin. Interestingly, they are all jötnar. As a consequence, most of Odins’ sons are actually three quarters jötun (since Odin himself is half jötun).

Frigg

Frigg, Odin’s primary consort and Queen of Asgard, holds a position of respect and power in Norse mythology. Their bond was not just marital; they were true partners, often working in tandem to influence events in both the realms of gods and mortals. Frigg’s wisdom often mirrored Odin’s, and while they had their disagreements—like any couple—their shared love for their children and their realm always united them.

Rindr

Rindr, a captivating giantess, became one of Odin’s co-wives. Their union was significant, especially with the birth of their son, Vali, who was fated to play a pivotal role in avenging Baldur’s death.

Grid

A resourceful jötun, Grid became another co-wife of Odin. Their bond was solidified with the birth of Vidarr, the silent god of vengeance.

Jörd

Jörd, personifying Earth itself, was another notable co-wife of Odin. Their relationship gave rise to none other than Thor, the thunder god, strengthening Odin’s connection to the very world he ruled over.

Gunnlöd

The jötun Gunnlöd’s association with Odin is underscored by their son, Bragi, the god of poetry and eloquence. Their union added an artistic touch to Odin’s lineage, weaving tales of inspiration throughout the Norse mythos.

Sons of Odin and his many wives

Odin’s lineage boasts a plethora of sons, each holding distinct roles within the Norse universe. These sons, birthed from different mothers, echo Odin’s vast relationships. Some are from the same mother, and in Tyr’s case, the parentage is a bit unsure.

- Baldur: Symbolizing light, purity, and beauty, Baldur was deeply cherished among the gods. He is a son of Odin and Frigg.

- Bragi: The skaldic god of poetry, eloquence, and music, Bragi is believed to be the son of Odin and the jötun Gunnlöd.

- Heimdall: The guardian of the Bifröst bridge, Heimdall’s exceptional senses are legendary. He was born from the nine daughters of Aegir and Ran, making his lineage truly unique.

- Hermod: Celebrated for his bravery as the gods’ messenger, Hermod undertook the perilous journey to Hel to retrieve his brother, Baldur. He is another son of Odin and Frigg.

- Hodr: Representing darkness and winter, Hodr’s accidental role in Baldur’s death adds a tragic layer to the tales. Like Baldur and Hermod, he is a son of Odin and Frigg.

- Meili: Though not as widely recognized, Meili, linked with exploration, is acknowledged as Thor’s sibling. His mother remains a mystery.

- Thor: The mighty thunder god, Thor, is renowned for his skirmishes against the giants. He is the son of Odin and the Earth goddess Jörð.

- Tyr: As the god of war and justice, Tyr’s deeds, especially during the binding of Fenrir, are commendable. While his father’s identity remains ambiguous, with both Odin and an unnamed jötun being contenders, his mother’s identity remains undisclosed.

- Vali: Conceived solely to avenge Baldur, Vali symbolizes swift justice. He is the result of Odin’s union with the giantess Rindr.

- Vidarr: Known as the silent avenger, Vidarr is prophesied to endure beyond Ragnarok. His birth is attributed to Odin’s relationship with the giantess Grid.

Odin’s Roles Among the Gods and Mythological Beings

Odin, the Allfather, was not the conventional benevolent ruler one might imagine. His multifaceted nature was evident in the complex web of stories that surround him. A god of war, wisdom, and magic, Odin was often at the heart of many a conflict and intrigue, guiding events with a hand that often seemed more bent on causing strife than preventing it.

Strife and Wisdom

In the Harbardsljod poem, a dialogue between Odin and Thor unfolds, revealing much about Odin’s nature. Taking on the guise of Harbard, a ferryman, Odin taunts and challenges Thor, displaying a clear penchant for sowing discord. Their exchange paints a vivid image of Odin’s wisdom juxtaposed with Thor’s strength and directness. While Thor is forthright and seeks immediate action, Odin’s responses are layered with riddles and deep meanings, reflecting his complex, cunning nature. Through their banter, it becomes clear that Odin values conflict not just as a means to an end, but as an instrument of growth and enlightenment.

The Prophecy and Tragedy of Baldur

Baldur’s unsettling dreams were the first omen of a series of events that would reveal the depths of Odin’s involvement in the destinies of the gods. Desperate for answers, Odin journeyed to the gates of Hel, where he woke a Völva from her eternal slumber. From her, he sought the truth behind Baldur’s fate, a truth that would be both tragic and inevitable.

Destiny’s Brutal Fulfillment

As Baldur’s death cast a pall over Asgard, Odin’s intricate involvement in the subsequent events unfolded. Determined to avenge his beloved son, Odin turned to Rindr. Their union bore Valí, a god born with a singular purpose: retribution. Valí’s rapid maturation—growing into a man in just a day—symbolized the urgency of the mission ahead. In a swift act of vengeance, he first slew Hodr, the unsuspecting instrument in Baldur’s tragic end. Later, in an act likely orchestrated by Odin, Valí was transformed into a wolf. In this form, he brutally tore apart Loki’s son, completing the cycle of revenge.

In understanding Odin’s role among the gods, it’s essential to recognize his profound influence in both fostering and resolving conflicts. While his methods might seem questionable, they underscore his commitment to maintaining the balance of power and ensuring the continuity of the Norse pantheon.

Odin: The God of Kings and Chieftains in Viking Society

In the tapestry of Norse beliefs, Odin held a unique position. While modern-day perceptions often conflate Odin with the entire Viking population, the truth is more nuanced. For the everyday Viking warrior or farmer, it was more likely Thor or his daughter, Thrud, who would be invoked before battles or in times of need. Odin, on the other hand, was the deity of the elite, the aristocracy of Viking society—chieftains, and kings. These leaders looked to Odin for victory in both warfare and the intricate dance of politics.

Odin and Tyr

Gods of Governance At the core of Viking society was a framework of laws and allegiances. These structures ensured order, defining relationships between individuals and clans. Loyalty and oaths were paramount. When Vikings swore oaths, they did so often invoking Tyr, the god of law and justice. Alongside him, Odin presided over the grander narrative, influencing the outcomes of battles and the machinations of politics.

Odin’s realm wasn’t just about warfare. It encompassed the strategies of leadership, the intelligence of decision-making, and the foresight required to lead a tribe or a kingdom. While Tyr ensured the sanctity of oaths and the balance of justice, Odin ensured the expansion and protection of territories and the power dynamics within and between tribes.

The Lokasenna and the Perception of Odin

In the Lokasenna, a poem that portrays a verbal duel between Loki and other gods, we find a raw and unfiltered view of Odin. Loki’s words are biting and revelatory, especially his taunts directed at Odin. The accusation that Odin allowed the “wrong” side to win in battles illuminates the distrust many everyday Vikings felt towards the Allfather. They saw him as capricious, unpredictable, and even treacherous—a deity who, driven by his own designs, might not necessarily favor the most righteous or deserving in battle.

Odin’s image as painted by Loki in the Lokasenna is that of a war-hungry, bloodthirsty deity, one who relishes in conflict and might tilt the scales according to his whims. Such a view resonates with the characterization of Odin as a god who’s more aligned with the ruling class, those who would benefit most from unpredictability in warfare and politics.

For the chieftains and kings of Viking society, Odin’s favor was crucial. While the common Viking might look to Thor for strength or Tyr for justice, the leaders invoked Odin for the wiles and strategies that would ensure their dominion. In understanding the Viking Age and its deities, recognizing these nuanced relationships is key.

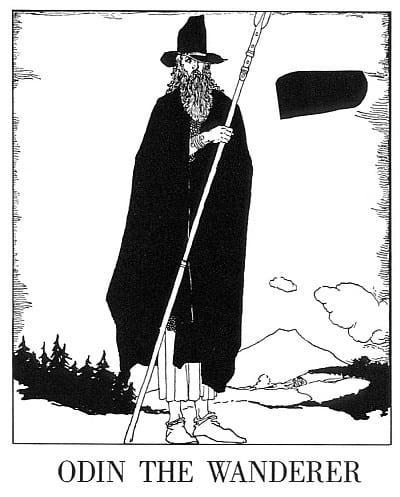

Odin’s Depiction in Norse Mythology

Odin, often portrayed as a wanderer, is one of the most recognizable figures in Norse mythology. His appearances in myths often underscore his dual nature as both a god of war and a god of wisdom. When he walks among the humans, his appearance is distinct, emanating an aura of enigma and authority.

Physical Descriptions

Odin is frequently described as an old man, distinct from other figures due to several key attributes. His long, flowing beard is a symbol of age and wisdom. Covering his form is a cloak, its dark blue or sometimes grey to black hues reminiscent of the vastness of the night sky or the deepness of the ocean, realms filled with mysteries. Atop his head is a wide-brimmed hat that shadows his face, specifically obscuring his missing eye, a testament to his sacrifice for knowledge. In some tales, he carries a staff, a further indication of his old age and a tool to assist him during his countless travels.

Relentless Quest for Knowledge

Odin’s pursuit of knowledge is a theme that runs consistently through many Norse myths. He’s not just a god of war but a deity whose thirst for wisdom knows no bounds. This drive is evident in how he sacrificed an eye to drink from Mímir’s well, gaining immense wisdom in return.

He delved deep into the mystical arts of seidr and galdr, seeking to harness their powers and understanding their secrets. But his quest wasn’t limited to just the arcane. Odin sought knowledge about the events transpiring across the realms, always keen to be a step ahead, always planning, always preparing.

Driven by Prophecy

While Norse myths don’t follow a linear timeline, there’s a strong indication that Odin became aware of the gods’ prophesied end at Ragnarök relatively early. This looming catastrophe became a central pivot around which many of his actions revolved. Whether he sought to prevent this grim fate or merely prepare for it remains a matter of debate, but what’s clear is his relentless drive.

Odin constantly added to his army of Einherjar, the chosen warriors destined to fight beside the gods during Ragnarök. He regularly sought out knowledge, from the völva in the Völuspá to the jötun Vafthrudnir in Vafthrudnirsmál. Odin’s interactions, whether they be battles of wit or actual combat, highlight a god constantly in motion, striving to accumulate knowledge, power, and allies in anticipation of the end of days.

Odin’s Symbols, Artifacts, and Animals

Odin, as one of the most revered and multifaceted gods of the Norse pantheon, is associated with a rich tapestry of symbols, artifacts, and animals. Each of these elements serves to further illustrate his complex character and the vast realms of his influence.

Symbols

The Horns of Odin, a triskelion-like symbol, is often found adorning Viking Age rune stones, jewelry, and coins. Representing a confluence of three interlocking drinking horns, this symbol is believed to be emblematic of Odin’s quest for the Mead of Poetry, a tale of wit, cunning, and the pursuit of wisdom.

Commonly referred to as the Valknut, this intricate symbol comprises three interlocked triangles. Found on various Viking Age artifacts, its significance is often linked to Odin and the afterlife. However, some, including myself, lean towards Snorri’s reference to the symbol commonly known as the Valknut, really being “Hrungnir’s heart”. The true name and meaning remain subjects of debate among scholars, but its connection to Odin is undeniable.

Artifacts

Draupnir Draupnir, the golden ring, is more than just a trinket. Every ninth night, this ring magically produces eight new gold rings of equal weight. A symbol of abundance and wealth, Draupnir was crafted by the skilled dwarf brothers Sindri and Brokkr and was among the treasures given to Odin.

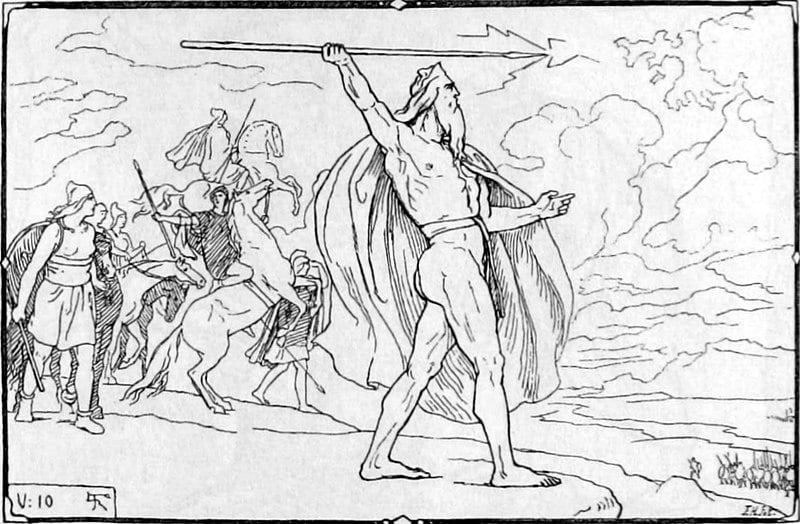

Gungnir Gungnir is no ordinary spear. Crafted by the talented dwarves, this spear is so well-balanced that it never misses its mark. A symbol of Odin’s authority and precision, Gungnir has played a role in various myths, including the instigation of the Aesir-Vanir war when Odin threw it over the enemy lines.

Animals

Ravens: Hugin and Munin Hugin (thought) and Munin (memory) are Odin’s faithful ravens. Each day, they fly across the world, gathering news and information, which they relay to Odin upon their return to Asgard. They epitomize Odin’s insatiable quest for knowledge and his omnipresent nature.

Wolves: Geri and Freki Geri (greedy) and Freki (ravenous) are Odin’s loyal wolf companions. They stay by his side, symbolizing his warrior aspect and the primal, fierce nature of battle.

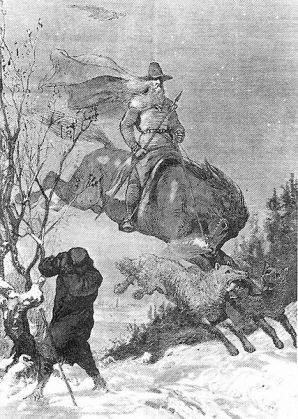

Sleipnir: Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse, is a marvel in Norse mythology. A creature of unmatched speed and endurance, he serves as Odin’s steed. Interestingly, Sleipnir’s lineage is as unique as his form; he’s the offspring of Loki, who took on the shape of a mare in one of his many deceptions, and the stallion Svaðilfari. This connection further intertwines the intricate relationships among the gods and highlights the complexities of their shared narratives.

Myths Surrounding Odin

Odin’s lore is vast and complex, with myths painting him as a multifaceted deity, embodying wisdom, war, poetry, and much more. While it’s challenging to cover every tale about him, the following myths offer a glimpse into his diverse roles and characteristics in Norse mythology.

The Creation

In the beginning, the void of Ginnungagap existed between the realms of icy Niflheim and fiery Muspelheim. From their meeting emerged Ymir, the first giant, and from him, the gods, including Odin and his brothers. These deities slew Ymir and from his body sculpted the world: his flesh became the land, blood the seas, and bones the mountains.

“Of Ymir’s flesh the earth was fashioned, and of his blood the sea.”

Mead of Poetry

Odin, driven by his thirst for knowledge, sought the Mead of Poetry, a drink that granted the gift of eloquence and wisdom. After deceiving and seducing the giantess Gunnlöð, he managed to escape with the mead, gifting a portion to humans.

“I suspect I would seem a ring-less man if I withheld such a treasure; I got out; I think I got past her.”

Lokasenna

In a heated banquet in Aegir’s hall, Loki insults the gods, and a sharp exchange ensues between him and Odin. Their exchange touches on their mutual past and foreshadows looming conflicts.

“They say that with spells in Samsey once, like witches with charms you worked; and in witch’s guise among men you went; I think that was a thievish trick.”

Harbardsljod

Odin, disguised as the ferryman Harbard, engages in a verbal duel with Thor. Their banter, filled with indirect allusions, showcases Odin’s wit and love for creating strife.

“Harbard I am called, but I was called Skald-bardi when I served another; now I am called Fox or Fiery-bardi.”

Baldur’s Death

Haunted by ominous dreams, Baldur’s fate deeply troubles the gods. Despite Frigg’s efforts to protect him, Loki orchestrates Baldur’s death through the blind god Hodr. Odin, deeply affected, sires Vali, who avenges Baldur by slaying Hodr.

“From Vala’s prophecy, most fell for me was that which I perceived on my son’s behalf.”

Ragnarok

The end of days sees Odin leading the gods into battle against the giants and monsters, including the wolf Fenrir. His ultimate sacrifice defines the gods’ last stand, paving the way for a world reborn.

“The wolf will swallow the father of men; but Vidar in vengeance will slay him.”

Through these tales, Odin’s complexities shine, revealing a god shaped by ambition, love, sacrifice, and an inevitable fate. Each myth underscores his unparalleled influence in the Norse pantheon.

Mentions in Norse Sources

Odin, as the chief god in the Norse pantheon, is mentioned extensively in various ancient sources. To get a clearer understanding of his depiction and role in these texts, it is beneficial to explore the mentions in the Poetic Edda, Prose Edda, and Heimskringla.

Poetic Edda

The Poetic Edda, a collection of Old Norse poems, is an invaluable resource for understanding Norse mythology and historical heroes.

Völuspá

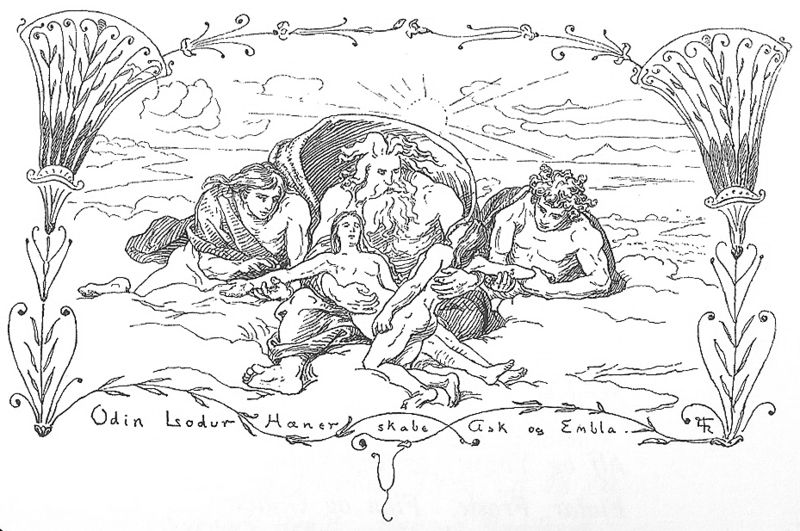

In the Völuspá, Odin engages in a dialogue with an undead völva, who recounts the history of the cosmos and predicts Ragnarök, the series of events that will bring about the end of the world. Notably, the creation of the first humans, Ask and Embla, is attributed to Odin and two other gods:

Spirit they possessed not, sense they had not, blood nor motive powers, nor goodly colour. Spirit gave Odin, sense gave Hœnir, blood gave Lodur, and goodly colour.

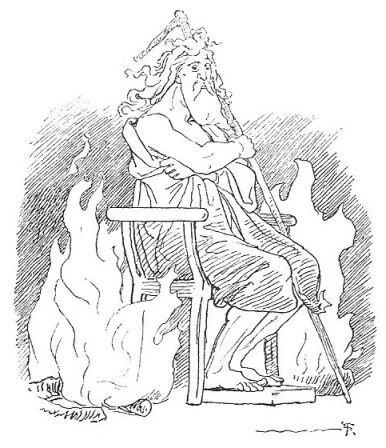

Grímnismál

In the Grímnismál, Odin reveals cosmic knowledge when he discloses secrets of the nine worlds to the young Agnarr while being tortured between two fires. The poem is named after Odin’s guise as “Grímnir”, which means “the Hooded or Masked One”.

Vafthrudnirsmál

The Vafthrudnirsmál captures a contest of wisdom between Odin and the giant Vafthrudnir. Odin, in disguise, poses a series of questions to the giant, and the poem culminates with the giant asking Odin what the Allfather whispered to his son Baldr upon placing him on the funeral pyre. This question serves to highlight Odin’s profound loss and deep wisdom.

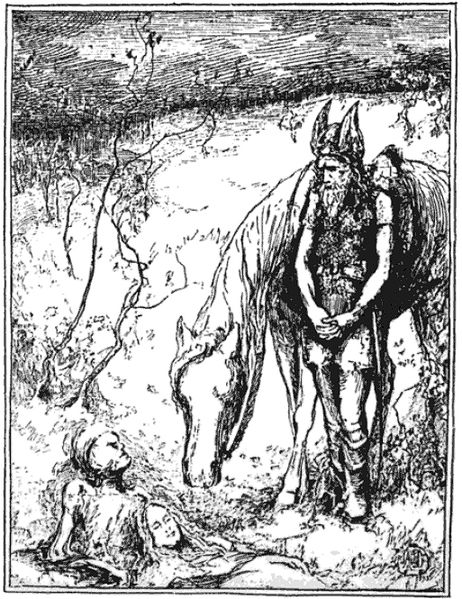

Baldur’s Dreams

In this short poem, the gods are deeply troubled by foreboding dreams had by Baldr. Odin rides to Hel to awaken a seeress from the dead to interpret these dreams. The seeress predicts Baldr’s imminent death, signaling the beginning of the end for the gods.

Lokasenna

The Lokasenna showcases the trickster god Loki hurling insults at the gods during a feast in Aegir’s hall. Odin faces Loki’s sharp tongue, but the Allfather manages to counter Loki’s barbs, highlighting the intricate relationship between the two.

Hávamál

The Hávamál is another essential poem from the Poetic Edda where Odin shares wisdom and recounts his quest for the mead of poetry:

I know that I hung on a wind-rocked tree, nine whole nights, with a spear wounded, and to Odin offered, myself to myself; on that tree, of which no one knows from what root it springs. Bread no one gave me, nor a horn of drink, downward I peered, to runes applied myself, wailing learnt them, then fell down thence.

Sigrdrífumál

In the Sigrdrífumál’s prose introduction, Sigurd witnesses a great light while journeying, leading him to a skjaldborg with a banner overhead.

Prose Edda

The Prose Edda is a collection of narratives and mythological explanations written by Snorri Sturluson.

Prologue

In the Prologue of the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson establishes a link between the Norse gods and historical figures. Odin is described as a mortal king who, due to his mighty deeds and influence, becomes revered as a god after his death. This euhemerized account sets a context for the reader, blending myth with history.

Gylfaginning

Odin’s character is introduced in-depth in Gylfaginning, where he rules Asgard and is described as the ‘father of all’. One of the most vivid descriptions reads:

“There the gods and their descendants lived and there took place as a result many developments both on earth and aloft. In the city there is a seat called Hlidskialf, and when Odin sat in that throne he saw over all worlds and every man’s activity and understood everything he saw.”

Odin’s Ravens and Wolves Odin’s connection to his ravens and wolves is explicitly mentioned, emphasizing his omniscient nature and unique eating habits:

“Odin sends Huginn and Muninn out at dawn, and the birds fly all over the world before returning at dinner-time. Odin gives all of the food on his table to his wolves Geri and Freki, requiring no food for himself, as wine serves as both meat and drink.”

Skáldskaparmál

The Skáldskaparmál, or “Language of Poetry”, discusses poetic diction by detailing the various kennings and heiti used by skaldic poets. Odin is often invoked, given his association with poetry and the legendary mead of poetry. This section details many stories, including that of how Odin won the Mead of Poetry by seducing its guardian, Gunnlöð.

Heimskringla and sagas

Ynglinga saga

The Ynglinga saga in Heimskringla provides an euhemerized account of the gods, depicting Odin as a great chieftain in Ásgarðr, the capital of the Æsir. The saga explains the customs and beliefs associated with Odin, emphasizing his influence and success as a warrior and leader:

Odin was a very successful warrior and travelled widely, conquering many lands. Odin was so successful that he never lost a battle. Before Odin sent his men to war or to perform tasks for him, he would place his hands upon their heads and give them a bjannak (‘blessing’).

In these texts, Odin emerges as a complex figure — a god of war, wisdom, and poetry, revered and feared in equal measure by gods and mortals alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

Odin sacrificed one of his eyes at Mímir’s well in exchange for unparalleled wisdom.

Among his many foes, the wolf Fenrir was foretold to bring about Odin’s end during Ragnarok.

Huginn and Muninn symbolize thought and memory, respectively, and they brought news from all realms to Odin.

Thor is Odin’s son, known for his strength and his hammer, Mjölnir.

This portrayal accentuates Odin’s role as a wanderer and seeker of knowledge.

Yes, Gungnir, his infallible spear, and Draupnir, a ring that multiplies gold, are among his most famed possessions.

Gallery

The Sacrifice of Odin

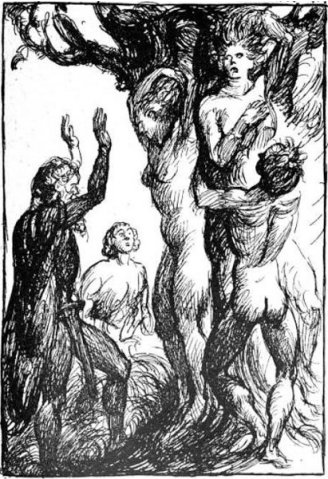

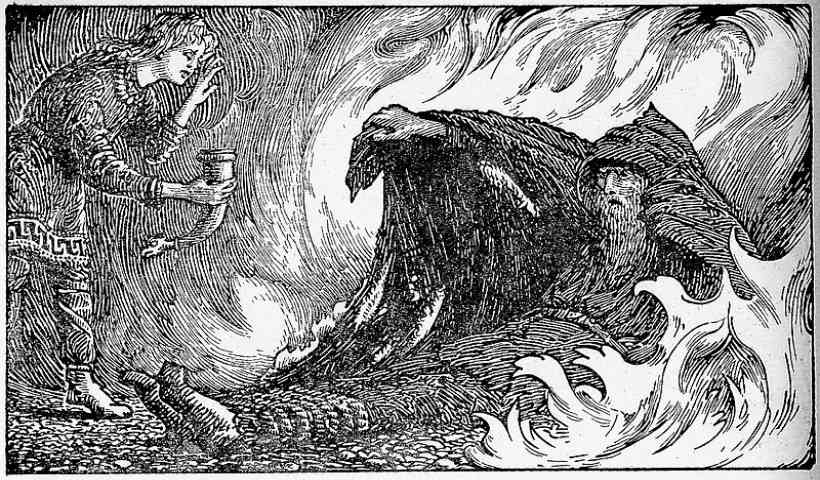

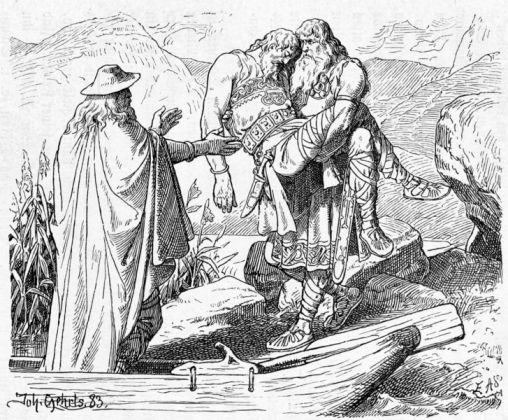

The Sacrifice of Odin An illustration of the three gods Loki, Odin and Hœnir, as narrated in the skaldic poem Haustlöng,

An illustration of the three gods Loki, Odin and Hœnir, as narrated in the skaldic poem Haustlöng, A depiction of the god Odin drinking from the well of wisdom.

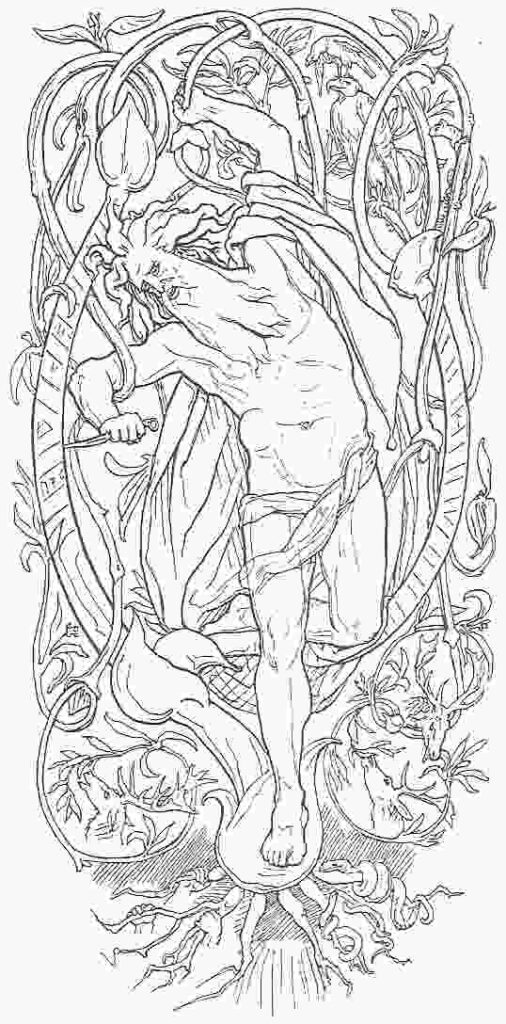

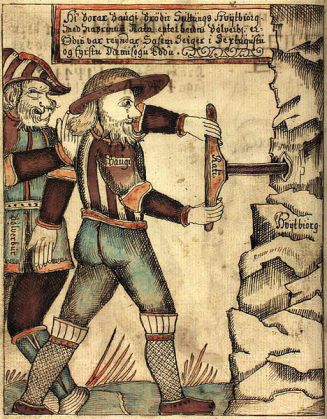

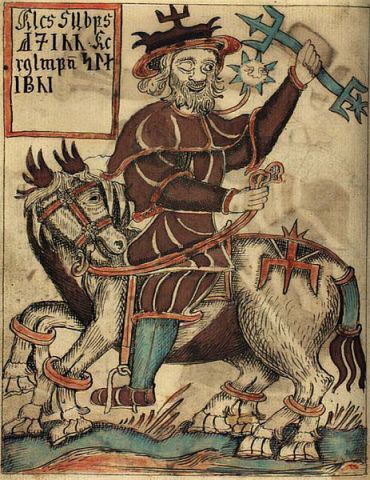

A depiction of the god Odin drinking from the well of wisdom. An illustration of Odin and the jötunn Baugi who bores through the mountain with a drill, from an Icelandic 18th century manuscript.

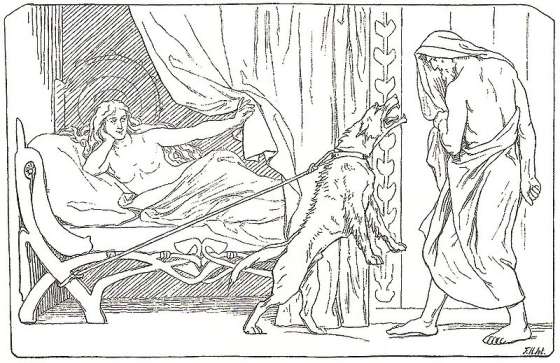

An illustration of Odin and the jötunn Baugi who bores through the mountain with a drill, from an Icelandic 18th century manuscript. Billingr’s girl watches on while Odin encounters the bitch tied to her bedpost. Inspired by Odin’s description found in Hávamál.

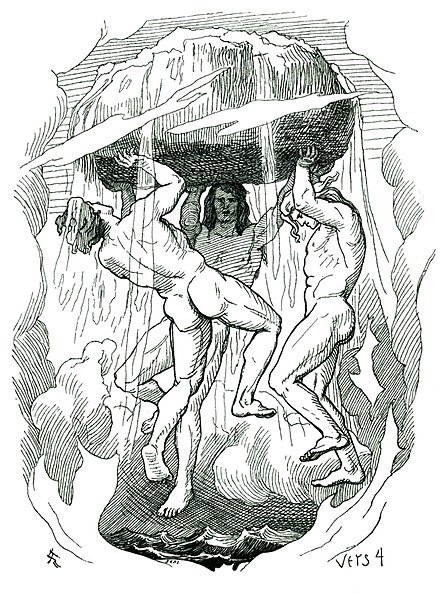

Billingr’s girl watches on while Odin encounters the bitch tied to her bedpost. Inspired by Odin’s description found in Hávamál. Hœnir, Lóðurr and Odin create Askr and Embla.

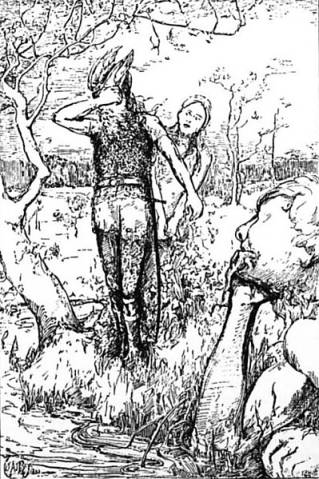

Hœnir, Lóðurr and Odin create Askr and Embla. Odin at the Brook Mimir

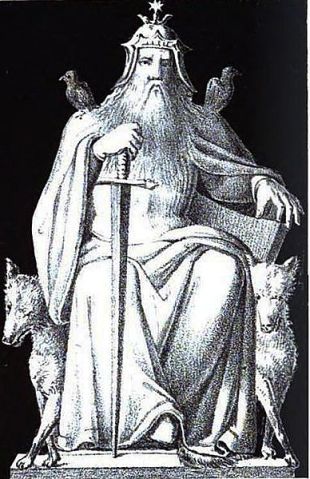

Odin at the Brook Mimir The Norse god Odin enthroned, flanked by his two wolfs, Geri and Freki, and his two ravens, Huginn and Muninn, and holding his spear Gungnir.

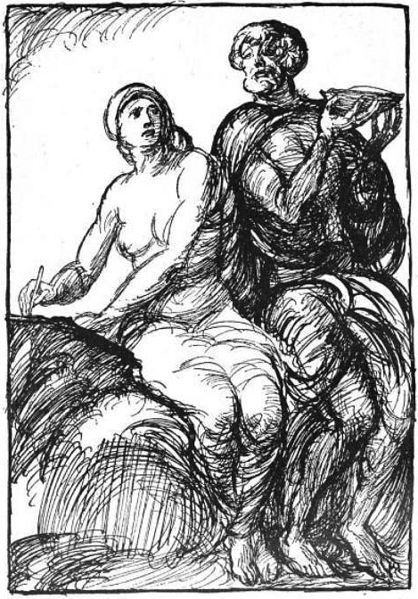

The Norse god Odin enthroned, flanked by his two wolfs, Geri and Freki, and his two ravens, Huginn and Muninn, and holding his spear Gungnir. Odin and Sága drinking together.

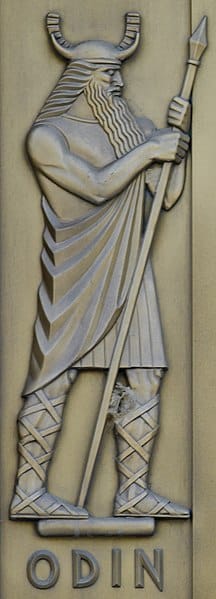

Odin and Sága drinking together. Odin, sculpted bronze figure by Lee Lawrie

Odin, sculpted bronze figure by Lee Lawrie Odin, Vili and Ve killed him and created the world of Midgard from his body

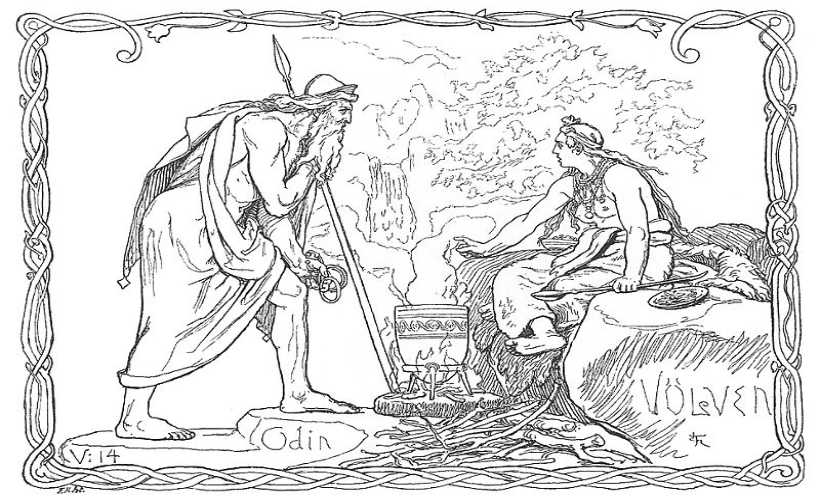

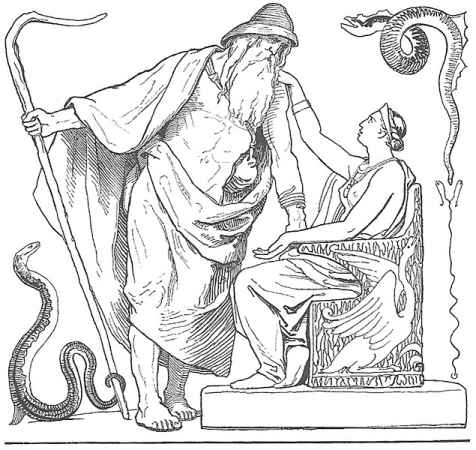

Odin, Vili and Ve killed him and created the world of Midgard from his body Odin holds bracelets and leans on his spear while looking towards the völva in Völuspá

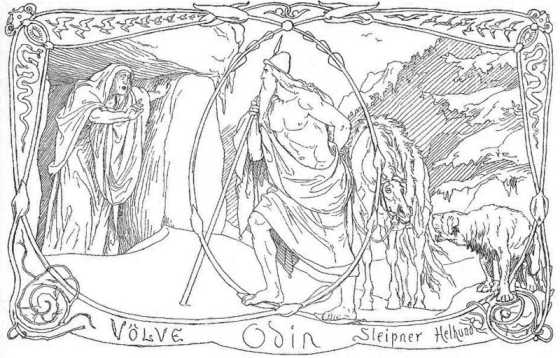

Odin holds bracelets and leans on his spear while looking towards the völva in Völuspá Odin and his horse Sleipnir meet with an unnamed völva in Hel as described in Baldrs draumar. Sleipnir and the Helhound Garm stare at one another.

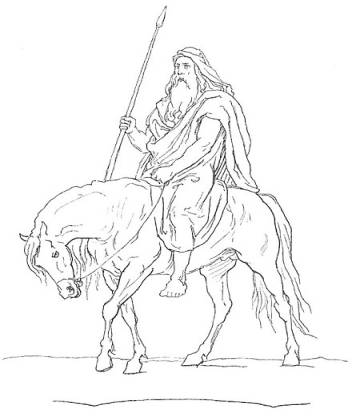

Odin and his horse Sleipnir meet with an unnamed völva in Hel as described in Baldrs draumar. Sleipnir and the Helhound Garm stare at one another. Odin holding Gungnir atop Sleipnir

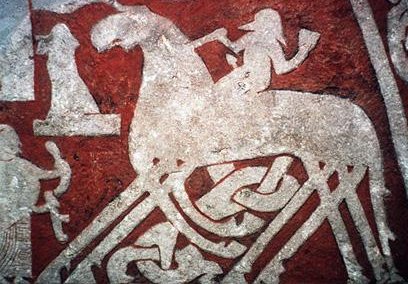

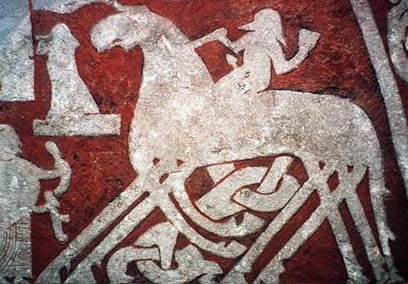

Odin holding Gungnir atop Sleipnir The Norse god Odin on his horse Sleipnir, featured on the Tjängvide image stone in Vallhalla.

The Norse god Odin on his horse Sleipnir, featured on the Tjängvide image stone in Vallhalla. Odin_and_Vafthrudnir

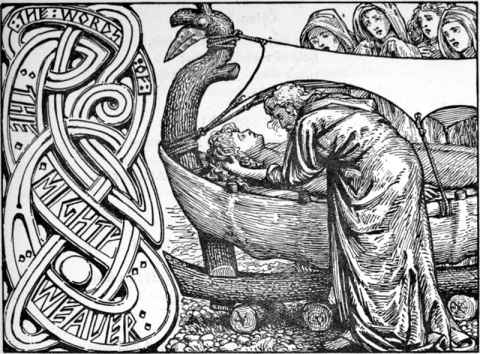

Odin_and_Vafthrudnir The god Odin whispers in the ear of the dead Baldr.

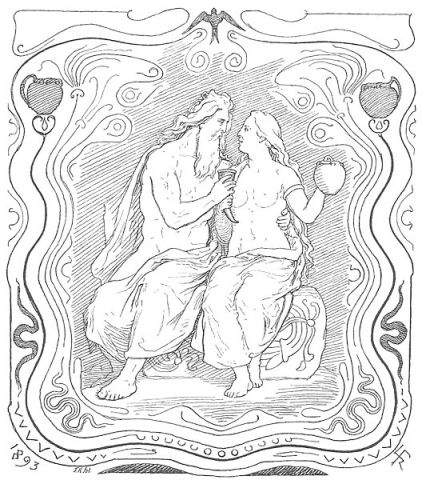

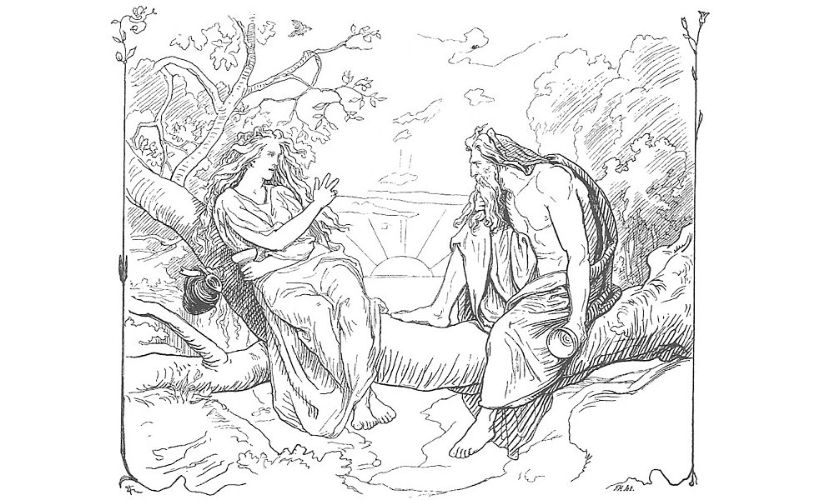

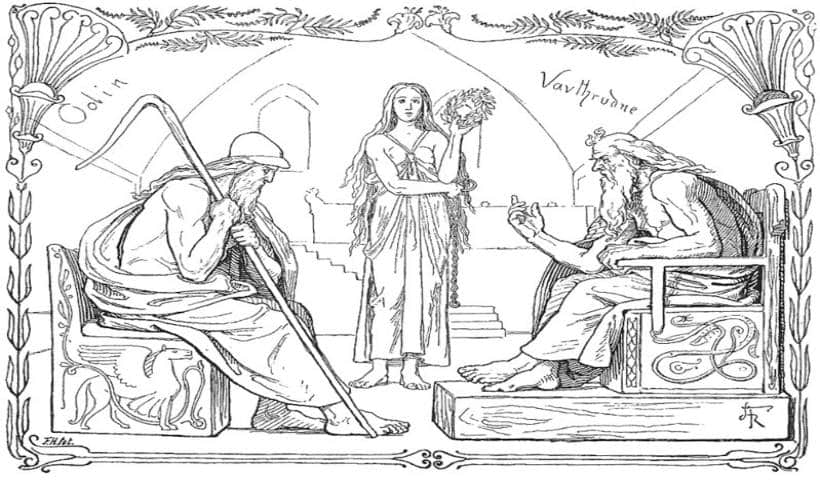

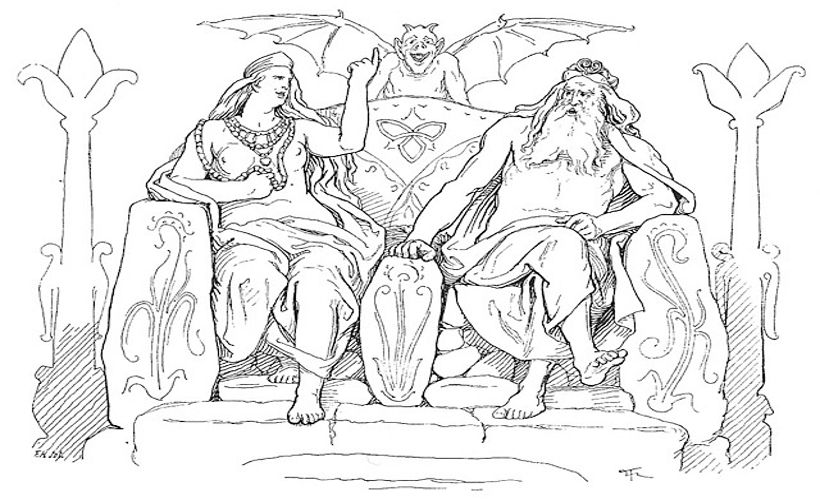

The god Odin whispers in the ear of the dead Baldr. The god Odin and his wife, the goddess Frigg, from the beginning of the poem Vafþrúðnismál (1895) by Lorenz Frølich.

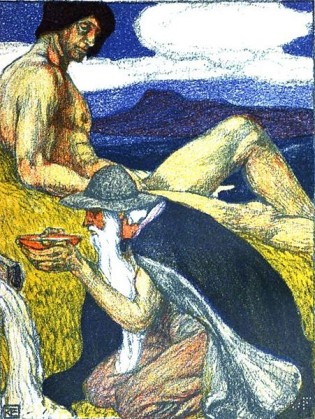

The god Odin and his wife, the goddess Frigg, from the beginning of the poem Vafþrúðnismál (1895) by Lorenz Frølich. Odin in Torment”: As the god Odin being tortured by Geirroð, he handed a full horn from which to drink by Agnarr, as described in Grímnismál.

Odin in Torment”: As the god Odin being tortured by Geirroð, he handed a full horn from which to drink by Agnarr, as described in Grímnismál. Odin enthroned with weapons, wolves and ravens.

Odin enthroned with weapons, wolves and ravens. The two ravens Hugin and Munin on Odin’s shoulders

The two ravens Hugin and Munin on Odin’s shoulders The goddess Frigg and her husband, the god Odin, sit in Hliðskjálf and gaze into “all worlds” and make a wager as described in Grímnismál.

The goddess Frigg and her husband, the god Odin, sit in Hliðskjálf and gaze into “all worlds” and make a wager as described in Grímnismál. Odin on his throne

Odin on his throne Odin riding Sleipnir, while his ravens Huginn and Muninn, and his wolves Geri and Freki appear nearby

Odin riding Sleipnir, while his ravens Huginn and Muninn, and his wolves Geri and Freki appear nearby Vidar & odin

Vidar & odin Frigg and Odin by Frølich

Frigg and Odin by Frølich Odin and Frigg look down from their window in the heavens to the Winnili women in an illustration by Emil Doepler, 1905

Odin and Frigg look down from their window in the heavens to the Winnili women in an illustration by Emil Doepler, 1905 Óðinn throws his spear at the Vanir host in an illustration by Lorenz Frølich (1895)

Óðinn throws his spear at the Vanir host in an illustration by Lorenz Frølich (1895) Odin’s hunt (August Malmström)

Odin’s hunt (August Malmström) An illustration of the god Odin on his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, from an Icelandic 18th century manuscript.

An illustration of the god Odin on his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, from an Icelandic 18th century manuscript. Sigmundur carries the body of his son Sinfjötli to the arms of Óðinn

Sigmundur carries the body of his son Sinfjötli to the arms of Óðinn Odin and his brothers create the world

Odin and his brothers create the world A depiction of the god Odin drinking with the goddess Sága (1919) by Robert Engels

A depiction of the god Odin drinking with the goddess Sága (1919) by Robert Engels The Children of Odin The Book of Northern Myths

The Children of Odin The Book of Northern Myths Odin Entering Midgard before Ragnarök.

Odin Entering Midgard before Ragnarök. Odin in the guise of “Grímnir,” growing concerned at the growing flames.

Odin in the guise of “Grímnir,” growing concerned at the growing flames. Odin’s Statue

Odin’s Statue The old man (Odin) places a sword into the tree Barnstokkr after entering the hall of the Völsungs.

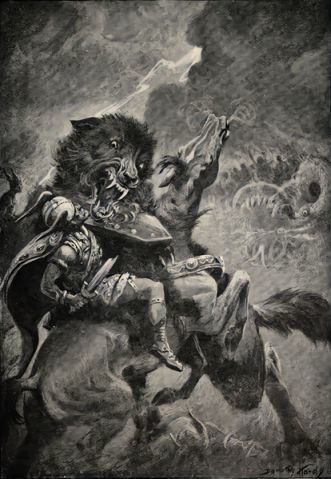

The old man (Odin) places a sword into the tree Barnstokkr after entering the hall of the Völsungs. A scene from Ragnarök, the final battle between Odin and Fenrir and Freyr and Surtr.

A scene from Ragnarök, the final battle between Odin and Fenrir and Freyr and Surtr.

Play Fun Norse Quiz

Is this article making you even more curious about Norse gods and goddesses? You can satisfy your curiosity by playing a fun Norse mythology quiz. This way, you can test your knowledge about Norse gods and goddesses, as well as fill in some gaps. Good luck and have fun playing!

Don’t forget to try our other games as well!