Mimir, recognized as the wisest being in Norse mythology, and his origins are shrouded in mystery. However, there are several clues to his story in the Eddas and other old texts. In this post I will try to piece together what is known, and what one might reasonably assume.

While his origins might be unclear, that he was the wisest of both the Aesir and the jotnar seems true. He was a trusted advisor to the gods, and even after losing his head, he continued advising Odin daily.

Mimir Key Facts

| Parents | Likely son of the jötun Bolthorn (Bölþorn) |

| Partners | None known |

| Siblings | Bestla, Odin’s mother (if he is indeed son of Bolthorn) |

| Offspring | None known |

| Tribe | TBD (Aesir or Jötun, or both?) |

| Old Norse name | Mímir |

| Other names | Mim, Mimer |

| The God of | Wisdom and Knowledge |

| Ass. Animal | Mimirs’ well (Mímisbrunnr) |

Name and Etymology

The name Mímir, like many ancient Norse names, carries a rich tapestry of linguistic history and etymological complexity. For historians and philologists, deciphering its origins can be as challenging as solving the riddles of the gods themselves.

The most widely accepted etymology among scholars suggests that Mímir’s name stems from a reduplication of the Proto-Indo-European verb *(s)mer-, which holds the intriguing meanings of ‘to think, recall, reflect, and worry over.’ This profound association with intellectual pursuits and contemplation aligns with Mímir’s renowned wisdom and sagacity in Norse mythology.

Kennings Involving Mímir

In the world of Old Norse poetry, kennings played a pivotal role. These poetic metaphors provided a colorful way to reference gods, giants, and various aspects of the Norse cosmos. Some kennings involving Mímir have emerged over time:

- Friend of Mímir: One of the most notable kennings, ‘Friend of Mímir,’ is used to describe Odin, the chief of the Aesir. It underscores the close connection between Odin and Mímir, emphasizing Odin’s reliance on Mímir’s counsel and wisdom.

- Mischief-Mimir: This kenning is employed to denote a jötunn, often associated with mischief and cunning. It hints at the enigmatic and sometimes unpredictable nature of these giant beings.

- Sökkmímir (Underground Jotnar): While not directly tied to Mímir himself, this term is used to describe great halls where jötnar reside. The connection lies in the assumption that, just as ‘Mischief-Mimir’ serves as a general kenning for jötnar, ‘Sökkmímir’ can be interpreted as ‘Underground jotnar,’ making it a fitting name for the hidden and subterranean dwellings of the giants.

These kennings not only add depth to Old Norse poetry but also shed light on the various facets of Mímir’s character, his connection with other deities, and the intriguing and sometimes elusive world of the giants.

Mimir’s Origins: Piecing Together the Enigma

Navigating the intricate tapestry of Norse mythology, one often finds themselves lost amidst the intertwining threads of legends, tales, and ancient poems. Such is the case with Mimir’s origins. It’s been debated among scholars and enthusiasts, with conflicting narratives muddying the waters. Drawing from my research and understanding, I’ve always leaned towards the belief that Mimir was, by birth, a jötun. His lineage, as I understand it, traces back to Bolthorn (Old Norse: Bölþorn), making him a sibling to Bestla and subsequently Odin’s maternal uncle. Various pieces of knowledge in ancient texts support this perspective, and if we apply a bit of common sense to the mix, we can bridge the gaps where the facts are less definitive.

Listed as a jötun in Nafnaþulur

The Nafnaþulur, a part of Snorri’s Prose Edda, offers a comprehensive list of jötnar. Intriguingly, Mimir ranks as the third jötun on this list. The relevant verse is as follows:

‘Giants I

I will make a listing of the giants; Ymir, Gangr and Mímir, Iði and Þjazi, Hrungnir, Hrímnir, Hrauðnir, Grímnir, Hveðrungr, Hafli, Hripstoðr, Gymir.’

This clear mention cements Mimir’s status among the jötnar, strengthening the claim of his jotun lineage.

Mímisbrunnr is in Jotunheim

Mímir’s Well of Knowledge, or Mímisbrunnr, finds its abode beneath one of Yggdrasil’s three roots, specifically the one reaching into Jotunheim. This geographical connection offers more than a subtle hint towards Mimir’s jotun heritage. If his well, the source of his unparalleled wisdom, is located in the land of the giants, it’s logical to infer that Mímir himself originates from and resides in Jotunheim.

The Unnamed Famous Son of Bolthorn

Hávamál’s stanza 140 presents an intriguing detail:

“Nine mighty spells I learnt from the famous son of Bolthor, Bestla’s father, and I got a drink of the precious mead, poured from Odrerir.”

Though this son of Bolthorn remains nameless, the clues are compelling. We have on one side an anonymous son of Bolthorn, who possesses significant wisdom and shares a close bond with Odin. On the other, there’s Mímir, a figure renowned for his wisdom, whose precise lineage is vaguely outlined in most texts. The notion that these two are one and the same doesn’t seem too far-fetched. Given the familiarity of Old Norse audiences with their deities and legends, it’s plausible that the text assumes this recognition from its readers, eliminating the need for overt clarifications.

Mimir Called “Old Jötun” in Grimnismal

In the poem Grimnismál, stanza fifty has Odin recounting his various names and exploits:

“I was Svithur and Svidir at Sökkmimir’s, And I tricked the ancient jötun; Son of Mithvitnir | the famous, I slayed single-handed.”

The term “Sökkmimir” here is particularly noteworthy. If it indeed alludes to Mimir’s dwelling, then this stanza provides another clue towards Mimir’s jotun identity. However, to play devil’s advocate, this might also be a more general reference, with Mimir’s name simply acting as a kenning for a jötun’s abode. The ambiguity persists.

In piecing together these various clues, a pattern emerges, suggesting Mimir’s jötun roots. However, as with many aspects of Norse mythology, interpretations can differ, and uncertainties can linger. The beauty of these ancient tales lies in their ability to keep us pondering, questioning, and connecting the dots across centuries.

Mímir might be both a jötun and an Aesir god

I hope you followed my reasoning to its logical conclusion, that Mímir is in fact a jötun. However, that isn’t necessarily the end of the discussion about “what he is”. While he is a jötun by birth, like several other Aesir gods, he could become an Aesir, basically by affiliation.

Njord, and his children Freyr and Freyja are several times named among the Aesir, but they were Vanir by birth. Furthermore, Tyr definitely has deep jötun roots, possibly both his parents were jotnar, yet he is an Aesir god of justice. Loki, who is also a bit of an enigma with regards to origins, is routinely named among the Aesir gods. In fact, many of the Aesir gods are half jötun.

At the end of the Aesir-Vanir war, Mimir along with Hoenir was exchanged for Njord and his children as hostages, or guarantors of peace. Seeing as all the others are gods it seems strange if, in this instance, Mímir wasn’t also considered to be of the Aesir.

The intriguing conclusion is that, like much in Norse mythology, his story is fluid. It is in no way linear and “logical”, instead it is multifaceted and not one or the other.

Play Fun Norse Quiz

Is this article making you even more curious about Norse gods and goddesses? You can satisfy your curiosity by playing a fun Norse mythology quiz. This way, you can test your knowledge about Norse gods and goddesses, as well as fill in some gaps. Good luck and have fun playing!

Do you want to learn more about the magical and powerful Jötunn? Then test your knowledge with this fun quiz game!

Don’t forget to try our other games as well!

Mímir’s Role and Depiction: The Sage of Yggdrasil and Beyond

Mímir’s significance in Norse mythology is multifaceted. Not only is he intrinsically tied to the well-known Mímisbrunnr (or “Mímir’s Well”), which is a fountain of profound knowledge and wisdom, but his connections go deeper, drawing him closer to the heart of the Norse cosmos itself.

The Wellspring of Knowledge: Mímisbrunnr

Mímisbrunnr is not just any well. Situated beneath Yggdrasil, the World Tree, it holds the secrets of the universe. Mímir, as the guardian of this well, drinks from its waters daily, amassing knowledge and wisdom that is unparalleled in the nine realms. This vast reservoir of ancient knowledge positions Mímir as not just a guardian but also a curator and recorder of cosmic knowledge. His role expands further as he becomes an adviser to the Allfather, Odin, offering insights derived from the deep wisdom of the well.

Hoddmímis Holt and Mímameiðr: Ties to Yggdrasil

The references to Hoddmímis holt and Mímameiðr underscore Mímir’s profound connection to Yggdrasil itself. Hoddmímis holt, often interpreted as “Hoard-Mímir’s holt”, is a sanctuary where Líf and Lífþrasir are prophesied to endure the harsh winters of Fimbulvetr, ensuring the survival of humanity. This holt, alongside the uniquely described Mímameiðr, a tree that stands resilient against fire and metal, sheltering life and even assisting pregnant women, is often equated to Yggdrasil. These two references, both seem directly associated with Mímir. Moreover, drawing him closer to the tree of life and underline his essential role in the preservation of knowledge and life itself.

Mímir’s Fate: The Talking Head

In terms of Mímir’s portrayal, an essential element in Norse mythology is his transformation. Following the Aesir-Vanir war, which is recorded as the ‘first war’ in the annals of Norse mythological events, Mímir meets a tragic fate. He’s decapitated, but thanks to Odin’s magic, his head remains sentient. It becomes a living, talking head, continuing to advise Odin and serving as a conduit of the wisdom drawn from Mímisbrunnr.

In conclusion, Mímir’s stature in Norse mythology is monumental. He’s not merely a figure connected to a well of wisdom but is deeply intertwined with the very fabric of existence through Yggdrasil. As a reservoir of ancient knowledge, a beacon of guidance to Odin, and a symbol of resilience, Mímir stands as a testament to the intricate and profound nature of Norse mythological narratives.

Myths about Mímir

Mímir, a being deeply entrenched in the fabric of Norse mythology, has his narrative woven into several significant myths. These myths not only reveal his unique stature and the reverence he commands but also underscore the intricate relationships he shares with the key figures of the pantheon, especially Odin. Delving into these tales gives us a holistic understanding of his pivotal role in the Norse mythological landscape.

The Aesir-Vanir War: Mímir’s Beheading

The Aesir-Vanir war, as depicted in the Heimskringla and Völuspá, is one of the earliest conflicts in the Norse cosmology. The war erupts due to a rising tension between the two tribes of deities: the Aesir and the Vanir. As hostilities come to a close, both factions seek to establish peace by exchanging hostages. Mímir, belonging to the Aesir, is sent to the Vanir along with Hoenir. However, the Vanir, feeling they were dealt an unfair hand when Hoenir proves to be less wise without Mímir’s counsel, retaliate by beheading Mímir. Odin, upon receiving his beloved uncle’s severed head, works magic to preserve it, allowing Mímir to continue advising him posthumously.

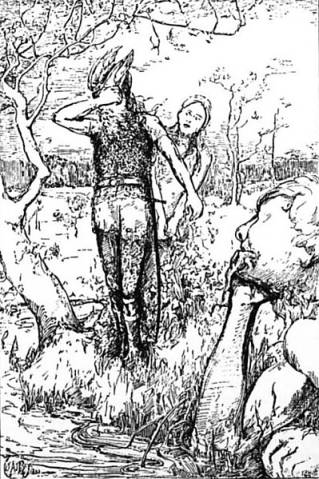

Odin’s Sacrifice: The Quest for Wisdom

Odin’s unending pursuit of knowledge and wisdom leads him to Mímir’s Well. Recognizing the well’s profound depth of wisdom, Odin is desperate to drink from it. However, Mímir, the guardian of this knowledge reservoir, demands a high price: Odin’s right eye. Demonstrating his unwavering commitment to enlightenment, Odin sacrifices his eye, placing it in the well. In return, he gets to drink from Mímisbrunnr, gaining immense wisdom that cements his position as ruler of the gods.

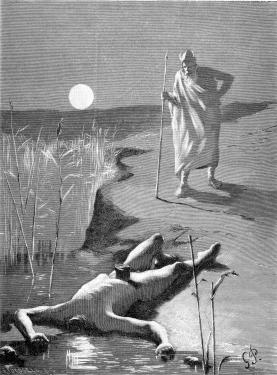

Mímir’s Counsel and Ragnarok

Odin, recognizing Mímir’s unparalleled wisdom, frequently seeks his counsel, especially when faced with significant decisions or events. As the foreboding events of Ragnarok approach, Odin turns to Mímir for guidance once more. On this fateful day, as the cosmos is engulfed in chaos, with gods and creatures clashing in a catastrophic battle, Odin consults the wise head of Mímir. Though the texts don’t provide a detailed account of their conversation, the very act of seeking counsel underscores the importance of Mímir’s wisdom even in the face of the world’s end.

In summation, the myths surrounding Mímir not only accentuate his importance in the pantheon but also highlight his intricate relationship with Odin, the chief of the gods. From being a casualty in a war to being the most sought-after adviser, Mímir’s journey in Norse mythology is both poignant and profound.

Mímir and Yggdrasil – The New Cycle of Life

In the intricate tapestry of Norse mythology, the interplay between characters and cosmic elements often bears deeper, underlying significance. Mímir’s connection to Yggdrasil, the World Tree, serves as a testament to this intricate narrative design. A deeper exploration into the links between Mímir and the sacred ash tree reveals insights into the cyclical nature of life and existence in the Norse cosmos.

Hoddmímis holt: Mímir’s Forest and the Sanctuary of Survival

The name Hoddmímis holt, which translates from Old Norse as “Hoard-Mímir’s holt,” offers a compelling hint towards Mímir’s association with Yggdrasil. This place of refuge is earmarked as the sanctuary where Líf and Lífþrasir, the human pair, are destined to survive the apocalyptic Fimbulvetr – the great winter preceding Ragnarok. This very location is described in both the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda.

In the poem Vafþrúðnismál, a dialogue between the god Odin and the wise jötunn Vafþrúðnir unfolds. Odin inquires about the fate of mankind during the grim winter of Fimbulvetr. Vafþrúðnir elaborates that Líf and Lífþrasir would find shelter in Hoddmímis holt, subsisting on morning dew, and it is from this pair that new generations will eventually arise.

This lore is further reinforced in Snorri Sturluson’s Gylfaginning. High informs Gangleri that Líf and Lífþrasir would take refuge in Hoddmímis holt, protected from the cataclysmic “Surt’s fire.” Following this destruction, these two survivors would give rise to a lineage that would repopulate the world.

Given these attestations, scholars and enthusiasts alike are inclined to interpret Hoddmímis holt as an alternate name for Yggdrasil. The link between Mímir and Yggdrasil becomes even more profound when considering Mímameiðr, another name suggestive of Mímir’s connection to the World Tree.

Mímir’s Enduring Wisdom: The Cycle Renewed

With Hoddmímis holt’s association with Yggdrasil and the survival of Líf and Lífþrasir, it’s tempting to assume that Mímir, too, could endure beyond Ragnarok. If the sanctuary of Yggdrasil could shield Líf and Lífþrasir, allowing them to be the progenitors of a new world, could not the wise Mímir, so integrally linked to this cosmic tree, also persist?

However, the texts don’t offer a conclusive answer. Yet, the implication is profound: Mímir, as the guardian of ancient knowledge, might be an enduring force. He would moreover bridge the old and the new, witnessing the old world’s end and the beginning of a new. This cyclical view of existence, with wisdom at its core, further elevates Mímir’s role in Norse cosmology.

Mentions in Ancient Texts

Mímir holds a significant place in Norse mythology, with references scattered across various ancient texts. From the Poetic, and Prose Edda to the sagas in Heimskringla, each mention provides insights into his role and importance. This chapter delves into these sources, offering a detailed look at Mímir’s presence in Norse tradition.

Poetic Edda

Völuspá Mímir is mentioned in the Völuspá, one of the poems from the Poetic Edda. Stanza 28 touches on Odin’s sacrifice of his eye to Mímir’s Well, illustrating the deed with, “Mímir drinks mead every morning from the Father of the Slain’s [Odin] wager.” In Stanza 46, as it paints the scene of Ragnarök, it references the “sons” of Mímir being engrossed in play as “fate burns.” This stanza also mentions the god Heimdallr blowing the Gjallarhorn and Mímir’s decapitated head advising Odin. Additionally, stanza 14 of Sigrdrífumál is another mention of Mímir’s speaking severed head. In the Fjölsvinnsmál, stanzas 20 and 24 reference Yggdrasil as Mímameiðr.

Prose Edda

Gylfaginning Chapter 15 of the Gylfaginning in the Prose Edda describes Mímir’s well. From which Mímir himself drinks to obtain great wisdom. For drinking, he uses the Gjallarhorn, which is also the name of the horn blown by Heimdallr to signify the beginning of Ragnarök. This well is said to be beneath one of the three roots of Yggdrasil, in the realm of the jötnar.

In Chapter 51, as Ragnarök unfolds, “Heimdall stands up and blows the Gjallarhorn with all his might. He awakens all the gods who then convene. Odin proceeds to Mimir’s Well, seeking counsel for both himself and his allies. The ash Yggdrasil quivers, and nothing, whether in the heavens or on earth, is devoid of fear.”

Skáldskaparmál Within the Prose Edda’s Skáldskaparmál, Mímir’s name emerges in various kennings. These include “Mím’s friend” (indicating “Odin”) in three sections, “mischief-Mímir”, a kenning for jötun.

Heimskringla

Ynglinga Saga Mímir finds mention in chapters 4 and 7 of the Ynglinga Saga, which is part of Heimskringla. Chapter 4 offers a more humanized account of the Æsir-Vanir War. According to Snorri, both factions decided to negotiate a truce. During this peace talk, they swapped hostages. Notably, the Vanir gave Njörðr and his son Freyr, while the Æsir sent Hœnir and Mímir. In Vanaheimr, Hœnir’s indecisiveness in Mímir’s absence led the Vanir to feel deceived. This resulted in Mímir’s beheading. Odin, however, preserved Mímir’s head with herbs and charms. Thus, empowering the head to continue to talk and share hidden knowledge with him. The saga further alludes to Odin keeping Mímir’s head, which continued to share insights from other realms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Odin sacrificed one of his eyes to drink from Mimir’s well and gain unparalleled wisdom.

Mímisbrunnr, the well of wisdom, is located in Jotunheim.

Mimir is often represented by his preserved, severed head, which continued to advise Odin.