The völva is a mysterious personage in Norse myth. Their profession was controversial even in Viking times when they were highly regarded members of society and well rewarded for their skills. There was a certain fear of their power to see the future and they were treated with great respect.

Odin himself called upon their skills many times when his own wisdom would not suffice. In our world of Midgard, they were commonly sought out by royalty and powerful chieftains to help them make the greatest of decisions. So who exactly are these unique and powerful beings?

wise women of seidr

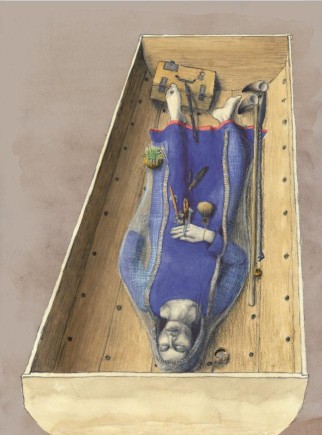

The wise women of seidr were known for their colorful garb made from the skins of a multitude of animals. They carried ornate staffs with which to wield their magic and a pouch to hold their talismans of divination at their waist.

While prominent in the myths and legends, it should not be forgotten that these were real figures in Norse society. The Fyrkat burial site in Denmark provides strong archeological evidence for their great importance and is the finest example of its kind.

The site dates back to the 11th century or perhaps even further to the time of King Harald Bluetooth in the 10th century. It is widely accepted to be that of a völva and it is clear from the contents of the grave that this individual was wealthy and belonged to the upper echelons of society.

These powerful individuals were unique in that they had both status in this world and free access to the other realms both above and below it. Not even kings could travel as freely between the realms as these wise women and men of old.

Travel between the worlds

Whether a legendary völva or one of the living seidr practitioners of Norse society, these shamans of the Viking age were uniquely gifted with this ability to travel. They used vardlokkur songs to enter a state of trance that allowed them to enter freely where none other might pass.

From these journeys, they brought back visions useful to those with great plans or simply to satisfy the burning curiosity of those who would know the future. For this reason, they were highly prized by all levels of society and held high status among their Viking peers.

At banquets, they were given a high seat from which to read the fortunes of all who came before them. The great and the humble were all the same to them and many a king was thrown into false confidence or fruitless anger by their cold pronouncements. None, however, could escape their fate once cast.

The memory of the Völva

When the völva of the Völuspá begins her prophecy she says that she ‘remembers’, as though she herself were present at the moment of creation. This does not mean that she was there corporeally, but that she sees it in her mind’s eye as if she were truly there.

This was a common custom among the völvas: to describe their visions as memories. Their great ability is to transcend time and go beyond their individual personalities to identify with something outside of time and more powerful even than the gods.

Odin is the greatest practitioner of seidr and yet several times sought the counsel of völvas, most famously that of the Völuspá. If he was capable of seeing the future with seidr, is it possible that he already knew what would happen but needed a powerful völva to validate his vision of Ragnarok?

Magic of the Viking age

Odin used runic magic to summon the völva of both the Völuspá and of Baldrs Draumar, but what kind of magic was used by the völvas to bring forth shades of the future into the here and now?

In ancient times before the descent of Christianity onto Odin’s people, magic was practiced widely. The two main branches of the old wisdom are called seidr and galdr. These arts were not meant to be practiced by all, with seidr, in particular, reserved mostly for women.

Galdr, ‘song’, ‘incantation’

This form of magic uses song and chanting to carry out the will of the magician or of those who have commissioned their service. Unlike seidr, both men and women commonly practiced this art. Their songs were accompanied by rites and ceremonies handed down through the generations.

The enchantments employed in galdr could ease childbirth, bring insanity to enemies, sink ships, raise storms, blunt weapons, soften armor, and ensure victory or defeat in battle.

The greatest of practitioners, among whom was Odin, could use this magic to raise and question the dead. In the Havamal, he claims the knowledge of eighteen galdr songs. His powers range from healing the sick to making a corpse descend the gallows tree to converse like a living man.

Those songs I know, which nor sons of men

nor queen in a king’s court knows;

the first is Help which will bring thee help

in all woes and in sorrow and strife.

The Havamal, Olive Bray Translation.

Galdr magic may be learned by any who has both the skill and opportunity to practice this ancient art.

Seidr, the magic of the Völva

Seidr was considered a darker form of magic and seen as unfit for use by the male sex. Although a man might learn it, he would be forever after deemed unmanly and male völvas were not held in the same high esteem as their sisters.

Women who practiced seidr, however, were highly regarded. They traveled far and wide in Viking times, taking up residence in the halls of chieftains and kings to tell the future, cast spells, and set out the destinies of heroes.

Galdr, although strong, does not hold the power of seidr which can determine the fate even of the gods. A fate once seen, can never be unseen and certainly never changed. Bad luck can be drawn down to curse the most powerful. Health, power, strength, and quickness of mind can all be stolen from one and given to another by a competent völva.

This stealing of power to win battles makes seidr the province of women who might not otherwise overcome their enemies in direct combat. Goddesses, priestesses, and other females of ambition and power were the masters of this art.

A great example of what a vardlokkur song of a Volva might have been like performed here by Faroese singer Eivor.

The Origins of Seidr: Heidr/Gullveig and Freya

Seidr enters the world of the Aesir when the völva Heidr pays a visit to Asgard. Her powers cause fear among the gods. They in turn try to burn her three times but each time she returns to life as strong as before.

It is possible that Heidr, meaning ‘fame’ or ‘bright’ came from Vanaheim and that her attempted murder was the cause of the great war between the gods. She is known also by the name Gullveig, meaning ‘gold-power’ or ‘gold-drunk’, and may well have been the Vanir goddess Freya.

Like Heidr, Freya is also blamed for bringing seidr into Asgard and is associated with gold. The Vanir goddess is said to have been the one who taught Odin the unmanly art. The Aesir were at first enthralled with her powers but came later to despise them, and gave her the name Gullveig as an insult.

Thus it is that the first war of heaven is bound up with the practice of seidr. The violent Aesir-Vanir war that led to the famous exchange of hostages has dark magic at its root with Freya, her brother Freyr and their father Njord passing into Asgard, while Mimir and Hoenir went to Vanaheim.

If Heidr and Freya are the same goddess, we cannot say for sure. It is also unknown if Freya was the first practitioner of seidr or if she merely brought it with her. If however, you seek to master seidr, then worship of Freya will be a good place to begin your journey.

Famous Völva and other practitioners of Seidr

Although some of the most powerful völvas were human or jötunn, their knowledge was so envied that many of the gods learned their ways as well. Odin was one of these.

Odin

The Allfather is the most powerful of all the practitioners of seidr. He alone, the most powerful of the gods, can share in the knowledge of seidr without shame. Yet even he was not above accusation and insult from the impertinent trickster god Loki.

Loki spake: “They say that with spells in Samsey once

Like witches with charms didst thou work;

And in witch’s guise among men didst thou go;

Unmanly thy soul must seem.”

The Lokasenna, Henry Adams Bellows Translation

Freyja

Freyja is maybe the most famous of the practitioners of seidr and is said to have taught Odin himself. Like the völva of Midgard, Freyja seems to have wandered freely from place to place practicing her art. Her visit to Asgard and the discord her magic led to were possibly the cause of the Aesir Vanir war.

In this respect, Odin behaved like any Viking chieftain when concerned for his clan. He summons völva to learn the future of his people and when they respond, in great detail, he is likely as dismayed as would any king be to learn of the inevitable destruction of all he holds dear.

The Völva (seeress) of Baldrs Draumar

The picture painted of the völva in this lively text is possibly the most colorful of all. She is raised from the dead by Odin and stoutly resists his efforts at interrogation. The Allfather must be robust in his questioning to compel her to reveal the meaning of Balder’s disturbing dreams.

The Völva (seeress) of the Völuspá

This Völva of the Völuspá is a truly mysterious figure. She claims to have memories from a time before even Ymir himself moved in the ice and before the worlds were nine in number. She was raised by giants but does not claim gianthood.

Although she describes herself this way in the opening lines, it is also possible that she was mortal, but her gift of seidr allowed her to clearly and accurately ‘remember’ the time of creation as though she was there. The vision of the völva was such that it felt like a memory to them.

The Völuspá, ‘Prophecy of the Seeress’

The Völuspá is arguably the most important document of Norse tradition and records this exchange between Odin and the unnamed wise woman. The text is preserved in the Codex Regius which dates back to 1270. Another version is found in the Hauksbók Codex which dates back to 1334.

Snorri Sturluson also quotes liberally from the Völuspá in his Prose Edda, which was composed around 1220 and is today preserved in manuscripts dating back as far as 1300.

Of these three main sources, the Codex Regius is acknowledged to be the most complete and to have the most logical organization of the material. The Völuspá is of such importance that it is the first text presented in the Codex and gives immediate profound insight into the old Norse world.

There are 66 stanzas for a total of 264 lines and in this compact form, we find the entire history of the gods together with predictions about their ultimate fate. The völva does not finish, however, until she has recounted what will become of the world after the final battle of Ragnarok.

The poem is reckoned to have been composed in Iceland as early as the 10th century giving many to believe that it is truly pre-Christian, giving would-be students and followers insight into the unsullied world of pre-conversion Norsedom.

Stories has been passed down through time

It may also be that the oral tradition takes us back even further to far earlier periods. The truth of this may lie beyond the scope of scholars to know. Perhaps only a völva might find it within her power to remember those ancient times.

Whether the manuscripts preserve a pure pre-Christian worldview or whether they are tainted with Christianity, we cannot be sure. Given that at least 200 years may have passed between the moment of inspiration and its transcription by Christian scholars, it seems unlikely although not impossible.

While the age and origin of the Völuspá remain a mystery, there is no doubt about its importance. The visions of the Völva chosen by Odin does indeed bring insight into the very end of their world.

The structure of the Völuspá

Like any fortune teller, the völva must first convince her audience. This is even more crucial when that audience is both a king and a god.

In stanzas 1 to 26 she describes her ‘memory’ of creation and subsequent events. It includes the war between Aesir and Vanir, the burning of Gullveig, and much more besides. Odin knows all of this well and was there for much of what she recounts.

Her goal, however, is not to inform but to convince. If Odin will accept her prophecy and give her payment, he must believe that she knows at least as much about these times as he does.

the völva establishing her credibility

This establishment of credibility includes a substantial list of dwarf names from stanzas 10 to 16. The reasons for this interpolation are not fully understood. Perhaps it was another ploy of the wise woman to convince the Allfather of her knowledge.

The seeress soundly convinces Odin of her transcendent power by describing to him some of his own secrets and of his quest for knowledge in stanzas 27 to 29. The King of Asgard, satisfied with the accuracy of her words, then rewards her.

Alone I sat when the Old One sought me,

The terror of gods, and gazed in mine eyes:

“What hast thou to ask? Why comest thou hither?

Othin, I know where thine eye is hidden.”

I know where Othin’s eye is hidden,

Deep in the wide-famed well of Mimir;

Mead from the pledge of Othin each mom

Does Mimir drink: would you know yet more?

Necklaces had I and rings from Heerfather,

Wise was my speech and my magic wisdom;

The Wise-Woman’s Prophecy, Henry Adams Bellows Translation 1936

Thus recompensed, and having gained the trust of the ‘terror of gods’, the wise woman begins her prophecy. This is the true reason for the Allfather’s visit and he must surely have had cause to regret his curiosity.

Reveals Ragnarok and the death of odin himself

In stanzas 31 to 58, the horror and despair of Ragnarok are made known, including the death of Odin himself. She further describes the deaths of Thor, Loki, Heimdall, Jormungand, Fenrir, and many more.

Now comes to Hlin yet another hurt,

When Othin fares to fight with the wolf,

And Beli’s fair slayer seeks out Surt,

For there must fall the joy of Frigg.

The Wise-Woman’s Prophecy, Henry Adams Bellows Translation 1936

By way of consolation, however, the seeress tells of the world that will follow this destruction. These hopeful verses foretell the return of Balder to the world of the living and then the rebirth of a beautiful and peaceful world.

In wondrous beauty once again

Shall the golden tables stand mid the grass,

Which the gods had owned in the days of old,

Then fields unsowed bear ripened fruit,

All ills grow better, and Baldr comes back;

Baldr and Hoth dwell in Hropt’s battle-hall,

And the mighty gods: would you know yet more?

The Wise-Woman’s Prophecy, Henry Adams Bellows Translation 1936

bitter sweet “happy ending” after all

At the end of the poem, she describes how she herself, like the corpse-bearing black dragon, will one day also go to Helheim at the world’s end, but not until after the bright hall of Gimle is built where the new generation of gods will take their ease in a peaceful world.

I see a sun-bright hall,

Gold-thatched at Gimle,

Where the Gods will pass

Their days in pleasure.

The black dragon flies,

Over dark-of-moon hills,

Bearing corpses to Hel.

Where I must go too.

The Völuspá, Nick Richardson Translation

In the long tradition of prophecy by practitioners of seidr, this one text is the most complete and most important. Sadly, it is also the most troubling of all to the greatest of all the gods.

Odin spends the remainder of his days trying to change, or prevent all that is foreseen, but like a man struggling against laws he does not understand, his every movement only takes him closer to the destiny he will avoid.

If Ragnarok is inevitable, we don’t yet know. So far the Gjallarhorn has not sounded and the gods, if they exist, still live peacefully in Asgard and Vanaheim.

Baldrs Draumar (Balder’s Dreams)

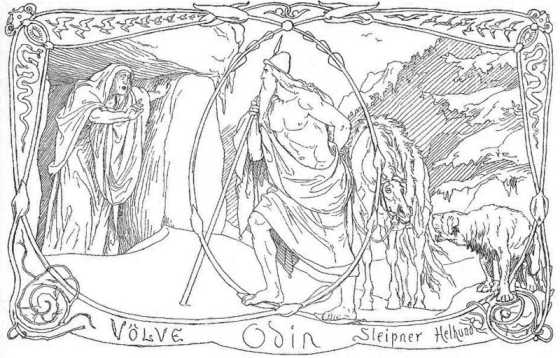

It is commonly thought that Odin used his runic magic to raise the völva of the Völuspá from the dead to question her. On another occasion, it is clear that the Allfather used his powers to summon a völva from her grave in Helheim to which he had traveled on his steed Sleipnir.

In the Völuspá, the wise woman is eager to convince Odin of her prescience and receives treasure as her reward. In Baldrs Draumar the seeress must be compelled by the Allfather to part with her vision of the future and when she has spoken, she wills him to depart and never return.

“What is the man, to me unknown,

That has made me travel the troublous road?

I was snowed on with snow, and smitten with rain,

And drenched with dew; long was I dead.”

Balder’s Dreams, Henry Adams Bellows Translation 1936

Three times she says to Odin: “Unwilling I spake, and now would be still.” But three times the Allfather compels her to continue with a commanding: “Wise-woman, cease not!” Each time she must continue under duress of Odin’s rune magic.

Similarities in the prophesies

The prophecy she delivers is closely related to the Völuspá. Does this mean the prophecy held all the more meaning for Odin? Did he learn of his son’s death here and then again, word for word repeated in the Völuspá, confirming the earlier vision?

Rind bears Vali in Vestrsalir,

And one night old fights Othin’s son;

His hands he shall wash not, his hair he shall comb not,

Till the slayer of Baldr he brings to the flames.

Balder’s Dreams, Henry Adams Bellows Translation 1936

The earliest manuscript of this text is found in the Arnamagnæan Codex, not the Regius as is the case with the Völuspá. Although this would make Baldrs Draumar a much later work, dating to the late 1600s or early 1700s, the style of the poem suggests it is far older.

Possibly the same author was involved

The overlap in detail of the prophecy of Balder’s death might suggest the works may be by the same person. This would date both of these poems to at least the 10th century. If it were the same völva who conversed with Odin on both occasions, perhaps only the gods can know.

Baldrs Draumar recounts how the gods were disturbed by baleful dreams that weighed heavily on Balder’s heart. As the Aesir are unable to decipher the meaning, Odin decides that a völva must be consulted.

The Allfather chose a Völva already dead which would make her all the wiser by her time in Niflhel. Her predictions echo or perhaps foreshadow those of the Völuspá. She tells Odin precise details of the death of his son and of the destruction of the world to follow.

Rebirth of the Völva

Although commonly seen as a character of myth the völvas were very real. It was not until the Christian era that their profession began to be forbidden by church officials and powerful converts to the new religion.

Despite this oppression of traditional belief the practice of seidr was never entirely extinguished. Now in modern times, there has been a resurgence of interest in the old ways. Many today claim to be the inheritors of this wisdom practice of ancient Norse society.

Featured Image Credit: Lorenz Frølich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons