A mostly failed attack by Danish vikings on a Frankish Empire fortress called Esesfelth in the summer of 817 likely helped set the stage for the Viking Age. The popular image of the early vikings is that of loosely organized chieftains and bands of marauders.

However, in what is today Denmark, they were quite organized. As early as the end of the 8th century, there was a Danish king named Sigfred who ruled. His kingdom covered what is today Denmark and stretched into part of modern day Germany. Denmark staying outside of the Frankish Empire to a large extent made the Viking Age possible. I think that otherwise, the people we know today as the vikings, would have been a much less powerful force.

Historical Background

During the Early Middle Ages, most of western and central Europe was dominated by the Franks. The Frankish Empire had expanded over several hundred years from its beginning in the north west of modern day France in the 5th century.

In 768, King Charles the Great (French Charles-le-magne) now known as Charlemagne, took the throne of the Frankish Empire after the death of his father. Then in 774 he was also declared king of the Lombards, a region covering more than half of Italy, including Rome. As his crowning title, he was declared emperor by the pope in Rome in 800. Becoming the first emperor of the former Eastern Roman Empire in three hundred years.

Under Charlemagne, the Frankish empire continued to grow, breaking the resistance of the Saxons in northern continental Europe, as well as subjugating several slavic tribes on their eastern border. One region he was unable to take control over though, at their northern border, was that held by the pagan Danes.

The Pagan Danes

At the end of the 8th century, the Danes were ruled by king Sigfred and they were Norse pagans. His kingdom, or region where he exerted his power likely covered all of Denmark as well as the west coast of Sweden and parts of eastern Norway. Little is known about king Sigfred. Most of what we know is found in old Frankish sources about their pagan neighbor to the north. In 777, the Frankish empire were battling the Saxons, and under their onslaught, the Saxon leader Widukind fled. Finding support and a powerful ally, Widukind found refuge with king Sigfred.

Smaller skirmishes and raids by the Danes into the northern parts of the Frankish empire ensued. Then five years later, in 782, a peace deal between the Franks and the Saxons seems to have been made with the assistance of king Sigfred. This saw Widukind return to Saxony where he would become the leader of a Saxon resistance which lasted until 785.

For many years there is no mention of the pagan Danes or their king, until an event in 798. Then, an emissary from Charlemagne to the court of Sigfred was killed by Saxons on his return trip. It is clear that the Danes seemed to be too strong for the Frankish Empire to take on. Moreover, while they beat the Saxons in battles, there was hardly any real peace between the Franks and the Saxons.

Instead, the Saxon region was more like a buffer zone between the Frankish Empire and the Danes. Oppressed by the Franks, and frequently raided by the Danes. It is hardly a surprise that many of them sought their future in Britain, across the English channel.

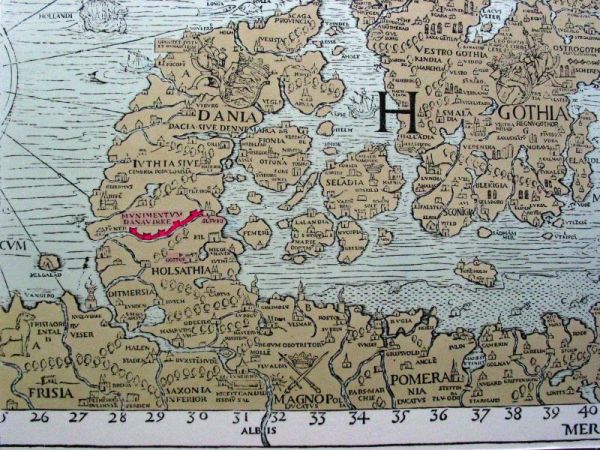

Danevirke – The “Danish Wall”

The Danevirke is arguably not as well known as other great defensive wall constructions. From the roughly same times, you have the Roman Hadrian’s wall in England, or Offa’s Dyke which marked the border of Mercia (England) and the pagan Celts, in today’s Wales.

Taking advantage of the terrain, the Danevirke was an earth and wooden palisades construction that cut across the southern border of the Danes, towards their Saxon and Obotrite neighbors to the south. Acting as an extension of a river to the west, and a bay to the east, and also in place cutting through marsh land, the Danevirke stretches for around 20 miles. Effectively cutting off the whole peninsula of modern day Denmark from northern Europe.

Having done some research on it for this post it’s clear that both the actual purpose and time of building is not entirely certain. What we do know is that it was likely begun already in the 7th century, and added to, or upgraded in several rounds.

Also, there are signs that have recently given support to a possible canal for moving barges and boats across the land, rather than having to sail around Denmark. For the large trade that was going on, this would make great sense. Rising between twelve and twenty feet, it would have been an effective way to stop any invasion from the south.

While the exact time of its first construction is unknown, the Franks themselves remark on it in the Royal Frankish Annals in 808. Then it is said to have been “newly finished”, likely meaning a series of updates or additions to it was finished. It’s not entirely clear however, if it refers to some part of the fortifications, or all in general.

Opportunity and Threat in Chaos and Change of Rulers

The exact dates, and even years are not a hundred percent certain, but as far as I can establish, king Sigfred ruled until 804, when he was succeeded by king Gudfred. They might have been father and son, but that is more a possibility than a certainty.

What is known is that under king Gudfred, the Danes seem to have both expanded upon and upgraded the Danevirke. Making use of more wood palisades, as well as stone masonry, the fortification was an imposing one. All but discouraging the Frankish Empire from trying an invasion. However, there was no peace either, and it seems the Danes made great use of their fortified position to do raids into Saxon, Frisian, and Frankish lands. The Danes also taxed parts of the region locked in between the Danes to the north and the Franks to the south.

In the next years there were ongoing conflicts, often involving local tribes aligned to either the Franks or the Danes. While all out war between the two ruling empires was avoided, there seems to have been a continuous proxy-war.

Death of king Gudfred and Danish Civil War

In 810, king Gudfred died under what is described as less than clear circumstances. This seems to have thrown the Danish empire into turmoil. King Gudfred had (at least) five sons, and several nephews, all likely interested in being rulers.

The Frankish empire entered into a short lived peace agreement with a King Hemming of the Danes (likely a nephew of Gudfred) in 811. The Danish king Hemming however, died the next year, in 812, setting the stage for civil war among the Danish vikings.

During the next couple of years, there was a power struggle between the sons of the late king Gudfred on one side, and Heriold/Harald, possibly a brother of Gudfred, and his sons. This first saw Gudfred’s sons flee to Sweden, only to return with an army and expel the “Harald faction” sometime in 813. At times aligned with Charlemagne and the Franks, the losing side, led by Harald Klak, found refuge in the Frankish empire.

The Esesfelth Fortress

In response to the ongoing conflicts, and outright threat from the Danes, the Franks had decided they needed a base further to the north to counter the influence of the Danes. This was planned and commissioned by Charlemagne in 808 or 809. Left in charge of this was the Frankish Count Egbert, who I understand as being the Frankish head of all matters in the Saxon areas.

Originally, the Franks had hoped that the Saxons, after being subjugated by the Franks, would be able to stand up to the Danes themselves. However, they had proven too weak, disorganized, or frankly unwilling, to really put up a fight against the Danes.

The building of the Frankish Esesfelth fortress, their first north of the Elbe river, began in 809 or early 810. This was basically deep in territory previously held by the Saxons, and was instead signaling how the Frankish empire expanded across Europe.

Construction and Position of the Fortress

Located close to the Stör river, a tributary to the large Elbe river, the fortress had a great strategic placement. Count Egbert decided to build the fortress on a moraine promontory which reached into a marsh area by the Stör river.

The medieval fortress, nestled within an oval-shaped interior spanning approximately two acres, was ingeniously fortified. Its northern, northwestern, and eastern perimeters were guarded by substantial turf ramparts, measuring up to thirty feet in width. Interestingly, the side that faced the Stör River appeared to be devoid of such ramparts, a strategic choice perhaps influenced by the natural landscape.

In a remarkable display of medieval engineering, the fortress was further protected by a dual moat system located to its east and north, just outside the ramparts. These moats were segmented by an earthen causeway that provided access to the fortress through a gate positioned near the northwestern edge of the spur. Notably, a third, shorter ditch was excavated west of the causeway, nestled between the two primary moats. The entrance itself was a formidable structure: a stone-paved gateway measuring 18 by 9 feet, seamlessly extending from the causeway and piercing through the ramparts. This gateway was a testament to the architectural prowess of the era.

Adding to its defensive might, the fortress boasted a series of ditches extending at right angles from the outer moat. This feature underscored the fortress’s status as a formidable defensive structure, particularly for the early 9th century. Additionally, a massive outer ditch on the eastern side further fortified the spur of the old moraine, encapsulating the fortress in a near-impenetrable ring of defense. This intricate network of ditches and moats, combined with the strategic use of natural terrain, made the fortress a marvel of medieval military architecture.

Louis and the Franks Prepares to Invade the Danes

Charlemagne died in January 814, leaving the empire in the hands of his son, Louis I, also known as Louis the Pious. The transition of power was orderly and not contested, Louis the Pious having been made co-emperor the year before. Along with the throne of the Frankish Empire, Louis also inherited the pagan threat to the north.

Despite the imposing might the Frankish Empire could bring to bear on their enemies, the Danes were an almost equally imposing military force. Having forced the tribes in modern day northern Germany and Netherlands to pay tribute to them for more than a hundred years.

In the early 9th century however, after king Gudfred passed, the Danes were thrown into a long period of internal turmoil. Around the time of Charlemagne’s death, Harald Klak, as mentioned above, had been thrown out by the Danes, so was in exile, living in the Saxon region with his men, under Frankish protection.

The Franks Go on the Offensive

With the fractured Danish society, it seems a lot of the different viking chiefs took the opportunity to raid both Saxon and Frisian towns and ports in the north west of the Frankish Empire. Rather than an all out war with the Danes, Louis the Pious and the Franks instead chose to back Harald and his men in his quest to regain the throne.

In 815, the Franks called on both the Saxons and the Obodrites to prepare to aid in an assault on the Danes, to restore Harald to the throne. The plan was to surprise them, coming across the frozen river Elbe in winter, and attacking the Danes when they least expected it. However, due to an unusually mild winter, the advances literally got bogged down, and they were unable to make any real advance until after the winter, in May. By that time the Danes were aware of the Frankish advances and likely understood their plans well.

While probably not numerically superior, the Frankish cavalry was respected and feared by the viking Danes. Heavily armored, foot soldiers with axes and swords were no match for the mounted cavalry. Not wanting to engage this force head on, the Danes pulled their warriors and around two hundred ships off the mainland, onto a large island.

The Franks and their subjugated Saxon and Obodrite forces pushed on for several days, south of the Danevirke wall. They basically only advanced through the very southern part of the Danes territory, until they reached the coast. After only a few days, the Franks realized they weren’t able to maintain the army just camped out in Danish territory, unable to reach their enemy across the water, and they returned home.

The Viking Danes Hit Back

After nothing much came of the Frankish attack, and after the majority of the Frankish forces had pulled out of the “buffer zone”, of the Saxon and Obodrites’ lands, that left their allies in a pickle.With the Danes as powerful as ever, and only a few hours away in a ship, they took the brunt of the vengeful Danes raids.

Sometime after this, in 816 or early 817, the Danes and their Obodritie neighbors came to an understanding. Very much squeezed between the Norse Danes and the Christian Franks, the Obodrites decided to side with the Danes, and try to push the Franks out of the Saxon region.

And so it was that the two forces banded together, and in the summer of 817, joined forces to attack the Frankish stronghold of the north, the Esesfelth fortress.

Sophisticated Two Pronged Attack

Knowing well how hard of a target the Esesfelth fortress would be, the Danes and their Obodrite partners planned to hit it from two sides. The straightforward way was obviously to come at it from the east, but that meant facing its main defences as well. In addition, the vikings moved part of their fleet, using inland rivers and at times actually rolling their boats across the land, to reach the large Elbe river. From the Elbe, they could sail, or likely row up the Stör river, right up to the Esesfelth fortress, coming at it from the south or west.

While the brazen attack seems to have taken the Franks by surprise, in the end they weren’t successful and the fortress proved too strong to be taken. Unlike the Romans, hundreds of years before them, or more sophisticated armies, the Danes didn’t have military equipment to effectively attack a fortified position. While certainly brave and battle hardened, they do seem to have been fairly calculating in their conflicts. As the initial attack didn’t work, the Danes and Obodrites retreated after a short siege before the Franks could muster up their forces from the south,

Aftermath of the Siege of Esesfelth

Hitting back in such a manner possibly put the Franks off the idea of invading the Danes all together. At least the Frankish Empire never again tried to take on the Danes in open battle. Instead, they continued their diplomatic efforts, supporting the ousted Harald Klak.

This strategy was employed by the Franks across their expanding empire, pitting locals against each other, or instating rulers who would bend the knee to the Frankish emperor.

This strategy bore some fruit as he was in fact taken back as co-ruler along with some of the Gudfreds’ sons in 821. Again, this was at a time of internal turmoil and disagreement among the ruling Gudfreds’ sons. However, the arrangement must have been perilous at best, and a few years later, Harald again was expelled along with his men/followers by the Danes, this time for good.

By resisting the Frankish Empire, shielded behind their Danevirke ramparts and considerable military might, the pagan north was allowed to flourish. The seafaring Danes, as well as the Norwegian vikings would boldly strike at their neighbors both in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and far, far to the west. for another few hundred years or more, before the Viking Age ended. Becoming a force for driving change across northern Europe and across the British isles at least until 1066.

Featured Image Credit: Otto Sinding, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons