Vikings in Britain – Their Lasting Legacy

England had been in contact with Scandinavians long before the first recorded Viking raids in Britain. It was, apparently, most often through trade that the Anglo-Saxons were familiar with their Scandinavian cousins, though, in the last decades of the 8th century, that would all change. Before we get to that, though, we need some important background information on Britain at the dawn of the Viking age.

England, as a concept, didn’t exist at the start of the Viking age. Indeed it likely wouldn’t exist at all were it not for the events of the 10th century. Especially the wars waged by Alfred the Great against the Great Heathen Army, also known as the Great Viking Army.

Before that happened, though, Britain held a number of independent kingdoms, with the Britons – the original inhabitants of the island – holding the western lands of Dumnonia, Gwent, Dyfed, Powys, and Gwynedd; the Scottish and Scots-Irish kingdoms of Strathclyde and Dál Riata, who were – like their British cousins to the south – constantly feuding with their Anglo-Saxon neighbors; and the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy.

Seven kingdoms of Britain

The seven kingdoms that would eventually become England, from north to south, were Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Kent, Essex, Sussex, and Wessex.

The Anglo-Saxons themselves were invaders from beyond the sea. They came from Frisia, the Saxon Coast, Anglia, and Jutland in northwestern Europe around the beginning of the 5th century and displaced the Romano-British culture that had existed since the Roman invasion and colonization in 43 CE.

These kingdoms were, at the start of the Viking age, nominally under the power of the kingdom of Mercia, but still retained enough independence to operate without the Mercian king’s permission in many matters. It was this independence that the Vikings would capitalize on: without a strong, centralized military to respond to the attacks, the heptarchy was vulnerable to the raids. Eventually, those invasions would mark the age of the Vikings in Britain.

The Early Vikings in Britain

Britain was no stranger to Scandinavians; the Jutes, who settled in Kent, came from modern Denmark, and a great number of Saxon and Frisians migrated there to escape persecution from the Frankish emperors as well. The Anglo-Saxons would dominate the remaining Romano-British peoples and override their culture, and establish the borders of what we now think of as modern England, Wales and Cornwall.

However, by the 7th and 8th centuries, things had stabilized somewhat- By then the heptarchy that ruled Britain appeared both stable and was integrating into the broader European community. International trade – or at least trade with people from abroad – was common enough that the arrival of a Scandinavian trader in southwest England did not raise too many eyebrows.

The first viking landfall

According to the Chronicon Æthelwardi, a Latin translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, three Danish viking ships anchored in Portland in 789, which caused the local Reeve, Beaduhard, to ride out to meet them. He did not recognize the men and ordered them to “go to the king’s town,” at which point they killed him.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle doesn’t detail what these Danes did after the death of Beaduhard, but it does state that they were “the first ships of the Danish men which sought out the land of the English race.” Whether or not these Vikings sought out the lands of the English people as a place for trade, settlement, or pillage is unknown, but Beaduhard’s death at their hands marked the beginning of a period of violence that lasted nearly 300 years.

Lindisfarne 794

A popular held notion is that, the Viking age in England started in 794 with the sack of Lindisfarne Abbey. The kingdom of Northumbria was close to Scandinavia, and the Abbey at Lindisfarne was a tempting target for anyone interested in violently redistributing wealth from the Church.

It was easy to target the Church, as monasteries, abbeys, and other centers of religious power were built on islands, peninsulas, or other isolated areas. The attack on Lindisfarne, though, is best remembered not only because of its sudden nature but because the Abbey was the center of religious power in Northumbria. As it were, St. Cuthbert – an important figure in early Northumbrian Christianity – had even ruled as bishop for a short while.

Further raids moved north, into Scottish and Irish territories for most of the early 9th century, until 835 when Danish Vikings raided the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent. The raids across coastal England continued to be relatively brief affairs, rarely lasting more than a few days or a week, until 855, when Danish raiders stayed over winter on Sheppey, and occupied the buildings there.

Unbeknownst to the English, the occupation of Sheppey was a prelude to the events of a decade later, when the Great Heathen Army invaded England and established a nearly two hundred-year-long claim to the northern part of modern England.

The Great Heathen Army

The early attacks and raids by Vikings in Britain were a precursor to the events of 865. That year saw the invasion, and occupation, of a sizable portion of Northeast England by a coalition of Scandinavian Vikings, warriors, and nobility. Modern academia prefers to call it the Great Viking Army. However the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle referred to it as the Great Heathen Army. Which today is perhaps what it’s most commonly known as.

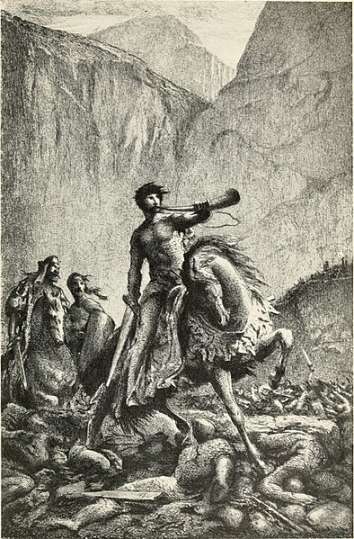

The start of the actual invasion and the reasons behind it are confused in both history and legend. In Ragnars saga loðbrókar, a 13th-century saga with its sources including Saxo’s Gesta Danorum from the 12th century, the invasion was led by three sons of Ragnar loðbrok. They were Halfdán Ragnarsson; Ívarr Hinn Beinlausi (aka Ivar the Boneless); and Ubbi Ragnarsson – and it was to avenge their father’s death at the hands of king Ælla of Northumbria.

Apart from that, though, there is no solid historical explanation for the invasion. However, Æthelward’s chronicle does lend some credence to the story in the Ragnars saga. Stating that “the fleets of the Viking tyrant Ivar the Boneless landed in England from the north” in 865.

The vikings takes East anglia

That year, the Great Heathen Army made landfall and set up their camp on the Isle of Thanet, in Kent. The Kentish paid a danegeld, or tribute, to the army in exchange for peace. However this was ignored and the Vikings launched raids and attacks all across the kingdom, and north into East Anglia.

Eventually, both Kent and East Anglia made peace with the army and gave them horses and gold in ransom. Over the course of the next year, the Vikings established East Anglia as their primary base for the invasion of greater Britain and the remaining kingdoms of the Heptarchy.

Vikings sack york in 866

At the end of 866, the Great Heathen Army marched northward again, this time northwards, to Northumbria, the kingdom of Ælla. They laid siege to, and conquered, York, which forced Ælla and Osberht, the king who Ælla had deposed in 862 or 863, to react.

They formed an army and attacked the Viking army that held York. While the details differ in both historical and legendary accounts, what is certain is that Æella was killed. Of course, the details are what make things interesting, and so here are the accounts of both Symeon of Durham, and Þáttr af Ragnars sonum:

“King Osbryht and Alia, having united their forces and formed an army, came to the city of York; on their approach, the multitude of the shipmen immediately took to flight. The Christians, perceiving their flight and terror, found that they themselves were the stronger party. They fought on each side with much ferocity, and both kings fell. The rest who escaped made peace with the Danes.”

While the wording may be a bit clumsy – the original Latin is not particularly clear – what Simeon reports is very similar to other contemporary reports from Æthelward and Bishop Asser. The Northumbrians attacked and the Vikings feigned a retreat. At that point, the Northumbrian kings pressed their advantage but were soon surrounded by a vastly superior Viking army. During the ensuing battle, Osberht and Ælla were both killed and the Northumbrians fled the field.

the victors write the story

In Ragnarssonar þáttr, the account is fairly similar except for Ælla’s end. Though, of course, in a revenge tale, there has to be some great satisfaction for those getting their vengeance.

“But when they clash, a good many leaders leave the king and go over to Ivar. The king was outnumbered then, so that the greater part of his forces fell, while he himself was taken captive. Ivar and the brothers now recall how their father was tortured. They now had the eagle cut in Ella’s back, then all his ribs severed from the backbone with a sword, in such a way that his lungs were pulled out there. As Sighvat says in the poem Knutsdrapa:

“Ivar, he who held court at York, had an eagle hacked in Ella’s back.”

After Ragnar’s sons got their revenge against their father’s killer, Ívarr declared himself king of Northumbria and Halfdán stayed with the army. The remainder of their brothers returned to their raiding across Britain and Europe.

The vikings looted at will across Britain

The Great Heathen Army, however, remained at large and continued their rampage across the Heptarchy. Ívars kingship was brief, however, and he installed a puppet leader before joining the army in its forays south.

Between 868 and 871, the Great Heathen Army successfully took Nottingham. Thus forcing the kingdom of Mercia to pay danegeld in exchange for peace, and marauded where they wished. In 870, returning to East Anglia, the army was attacked by king Edmund of East Anglia. Edmund’s army was defeated, and he was captured, tortured, and executed.

With that, the line of East Anglian kings came to an end. Edmund was soon after venerated as Saint Edmund the Martyr. There were setbacks in 871, with Alfred of Wessex – the future king Alfred the Great – defeating the Viking army at Ashdown and keeping them from encroaching further into Wessex.

The fall of Mercia 874

In 874, the army finally conquered Mercia, exiling their king and installing Ceolwulf as their puppet king. Effectively ending their invasion as a single military force. Halfdán took a band of warriors northward and raided the Picts and the British kingdom of Strathclyde, to the north. Eventually returning to Northumbria, where he broke up his band, granting land to his warriors. Himself going to Ireland with his brother Ívarr.

The second band of Viking warriors was led by Guðrum, a Danish war leader, and established a base in what is now Cambridge, where they raided Wessex, taking the market town of Wareham in 875. After a number of successful raids, Alfred – now king of Wessex – met and defeated Guðrum at the Battle of Edington in 878, setting the borders between Wessex and the Danelaw, and effectively ending the invasion of the Great Heathen Army, 13 years after it had begun.

The Last Vikings in Britain

After the treaty of Wedmore in 878, which established the borders between the kingdom of Wessex and the Danelaw, there was very little in terms of concentrated Viking activity in England. In 892, two new armies arrived in the Danelaw – one in Appledore, Kent, and the other in Milton Regis, Kent. Promptly beginning to raid the Wessex borders.

Unfortunately for the new invaders, the defenses that Alfred the Great had established between the end of the first invasion and the second were extremely strong. Leading to the Viking armies eventually disbanding, some going to Normandy and others settling in East Anglia.

vikings meet more resistance across britain

The next 90 years were a series of disasters for the Vikings in Britain. Despite a number of small military successes after the death of Alfred in 899, the Anglo-Saxons – led by Edward the Elder – put down a rebellion in the Danelaw that was led by Alfred’s cousin. In 909 they attacked Northumbria with a combined West Saxon and Mercian army.

The Northumbrian Vikings were roundly defeated and sued for peace, but in the next year attacked Mercia in revenge. It was a successful raid, with a fleet of ships sailing down the River Severn to lay waste and plunder the heart of the kingdom of Mercia.

But as they sailed back to Northumbria, a combined army of Mercians and West Saxon soldiers trapped the fleet. Annihilating the Viking force. It was the end of the last great Viking raiding army in England. Marking the beginning of the total rule of England by one monarch.

By 918, king Edward the Elder, the first king of a united England, and his niece, queen Æthelflæd of Mercia, had all of the lands in the Danelaw south of the River Humber. Effectively ending Viking rule in England.

By 927, Edward’s son, Edmund, had destroyed the last Viking kingdom in modern England, taking York, and raided deep into Scotland. The battle of Brunanburh was the final, decisive defeat of Viking power in England, despite a short revival between 948 and 954 when Eiríkr blóðøx ruled Northumbria from York.

Military weakness invites new viking raids

In 980, as English political power consolidated but their military strength waned, Viking raiders attacked again. Over the next decade, the English crown paid huge amounts of danegeld as protection money to stop the violence. By 1002, the English people and nobility had had enough, and demanded decisive action. King Æthelred the Unready committed to that.

In 1002, on St. Brice’s Day, he ordered all Danes living in England to be executed. The resulting massacre prompted king Sveinn tjúguskegg – Sweyn Forkbeard – of Denmark to attack in retaliation. In 1003 he began a series of raids, devastating East Anglia, Thetford, and Norwich.

The violence continued for the next decade. In 1009 the warlord Þorketill started a three-year-long raid across England. In the process taking over 48,000 pounds of silver and capturing the Archbishop of Canterbury. Who was killed in a drunken incident with bored Vikings.

Æthelred flee england for normandy

In 1013, Sweyn again invaded, and this time forced Æthelred to flee England for Normandy, giving him the English crown. Despite that victory, Sweyn died inside of a year and Æthelred returned to claim the throne. Three years later, in 1016, Sweyn’s son, Cnut – or Canute the Great – returned with an army. Defeating the English at Assandun, uniting the Danish and English crowns until his death in 1035.

After Cnut’s death, there was a period of turmoil in the Danish court. The English chose to be ruled in regency by Harold Harefoot. Following this, in 1037, he was made king Harold I of England.

1066 marked the end of the Viking Age in England when king Haraldr harðráði of Norway invaded to take advantage of the succession crisis after the death of king Edward the Confessor. Despite a number of initial victories, including a major victory at Fulford which gained him control of York, Haraldr was ultimately unsuccessful in his attempt to wrest England for the Norwegian crown.

Stamford bridge 1066

His army was caught unaware at Stamford bridge by king Harold Godwinson of England and decisively defeated. During the battle, Haraldr was killed as he fought a desperate defense, completely surrounded by the English and outnumbered. He was unarmoured, as were most of the Norwegians since the army had not been aware of the English advance. With his death, the Viking Age in England officially came to a close.

Despite that seemingly down note, three weeks later the English were decisively defeated at the battle of Hastings. Then William, Duke of Normandy, a descendant of Hrólfr, the Viking warlord who became known as Rollo of Normandy, became king of England. The House of Normandy reigned in England until 1135 when William III Rufus died without an heir.

Bibliography

- Borovsky, Z. (Ed.). (1998). Ragnars saga loðbrókar. Retrieved from https://www.snerpa.is/net/forn/ragnar.htm

- Borovsky, Z. (Ed.). (1998). Þáttr af Ragnars sonum. Retrieved from https://www.snerpa.is/net/forn/rag-son.htm

- Campbell, A. (Ed.). (1962). Chronicon Æthelwardi, The Chronicle of Æthelward. (A. Campbell, Trans.) London: Thomas Nelson and Sons.

- Ragnars saga loðbrókar. (2003). (C. Van Dyke, Trans.) Denver: Cascadian Publishing.

- Saxo Grammaticus. (1905). The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus. (O. Elton, Trans.) New York: Norroena Society. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1150/pg1150-images.html

- Symeon of Durham. (1855). The Church Historians of England (Vol. III). (J. Stevenson, Trans.) London. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/churchhistorpt203unknuoft/churchhistorpt203unknuoft_djvu.tx

- The Tale of Ragnar’s Sons. (2005). (P. Tunstall, Trans.) Retrieved from https://jillian.rootaction.net/~jillian/world_faiths/www.northvegr.org/lore/oldheathen/055.html