Ragnar Lothbrok Sigurdsson, (Old Norse Ragnarr Loðbrók) has risen from the old sagas to become one of the best known vikings of all time. There are actually quite a few well known vikings. Leif Erikson will forever be remembered as the one discovering America. Harald Hardrada is immortalized as “The Last Viking King” after falling at the battle of Stamford Bridge. Olaf the Holy became a saint after dying at the Battle of Stiklestad.

With the advent of the Vikings TV show however, Ragnar Lothbrok has become immortal. Greatly helped by the excellent portrayal by actor Travis Fimmel, Ragnar’s rise and fall was detailed in all its gore, ambition, hope and loss.

However, the Ragnar of the show is not historically correct, and there are great creative freedoms taken with the source material. Having said that, I want to point out that the story of Ragnar Lothbrok was really popular in the Viking Age as well.

In this post I am exploring what we really know for sure about the man Ragnar Lothbrok. Where did he come from, who really were his wives and children, and what happened to him in his decidedly eventful life.

The Many Sagas, Poems and Mentions of Ragnar Lothbrok

Before diving into the life of Ragnar Lothbrok, it’s important to understand what the sources are. Even more so since there are several sources, sometimes contradictory, some more legend than fact, and some are possibly about a different Ragnar.

The story of Ragnar’s life took place some time in the first half of the 9th century. From that time we have less in the form of hard facts about the various kings etc. than we have just a few generations later. However, that is not to say we don’t have sources mentioning Ragnar Lothbrok, there are actually quite a few.

I will try to go through the most important ones, and how they fit into the greater legend and history of Ragnar. This is not a full list of all stories or mentions. However, put together I believe they paint a great picture of what we can say are known facts, and what is myth about Ragnar Lothbrok.

The Icelandic Sagas and Old Norse Poems

Among what are arguably the more classical sources are the two old Icelandic sagas, The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and the Tale of Ragnar’s Sons. The first was likely written down in the 13th century while the latter was written down in the 14th century, both likely in Iceland. They were possibly based upon even older manuscripts, or a strong tradition of passing down stories orally.

Out of the two, it is the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok which is the most detailed and by far the longest. In this saga, Ragnar’s life and some of the events are covered in great detail, while others are largely omitted. Just as in the Tale of Ragnar’s Sons, a great deal of focus is on his different sons, their exploits before his death, and their revenge after he is killed.

Make no mistake though, they are not especially strong on hard facts and figures. They are instead more steeped in the lore and mythical legends of the time. In the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, much is made out of how the brothers have to beat a holy, or magical, battle-cow as well as how they all react to the eventual news of their fathers death.

Old Norse Poems

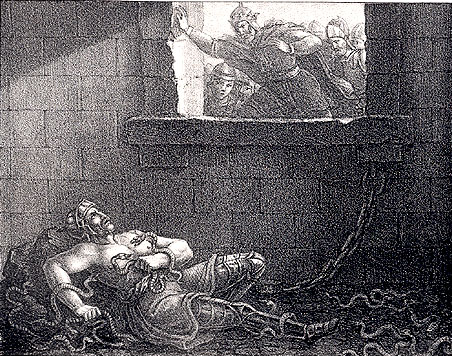

Somewhat in the same format, although shorter and with no narrative prose between the verses is the Old Norse poem Krákumál, or Lay of Kraka. Likely written by a Norse skald on the Hebrides or Scottish islands in the 12th century. It is written as a monologue by Ragnar as he lays dying in the snake-pit of Ælla. The poem consists of twenty nine verses, mostly recounting Ragnar’s life and deeds, see the first verse below.

Krákumál verse 1

We struck with our sword.

It was not long ago,

We to Götaland went

to slay the burrowing-wolf*.

Then we married Thora;

ever after, among men,

having stabbed the heather-fish,

Lothbrok would be my name.

I stabbed the Earth-loop**,

with a shining steel blade.

*heiti for snake, **kenning for snake

Another mention in Old Norse poems is found in the Knútsdrápa. Written by court skald Sigvat Thordasson in the first half of the 11th century. While not centered on Ragnar, it does mention the revenge by his sons on Ælla, carving the blood eagle on his back.

Knútsdrápa, verse 1

And Ívarr,

who resided at York,

had Ælla’s back

cut with an eagle.

The revenge taken upon Ælla is cited in several sources, along with mentions of Ivar being a harsh king so it does seem to be an acknowledged fact of the time.

More Historical Accounts in Danish Sources

There are far more actual historical mentions written by outside parties, like Anglo-Saxons, Franks or even later-age Danes. They are either contemporary sources, or historically minded Christians writing about recent history in various old chronicles.

Having already been Christianized and with a number of monks and others versed in writing, many mentions and more historical sources are found in various chronicles

However, it is when I dived into these various accounts, I quickly lost track of what Ragnar actually did in his lifetime. There are slightly, or widely different stories about Ragnar, and then there are a lot of mentions of his many sons. In several instances you can learn something about Ragnar Lothbrok from the story of one of his sons.

The Roskilde Chronicle

This is a short book, believed to have been written, or at least finished between AD 1140 and AD 1143. The book, written in Latin, was likely written by a priest at the Roskilde Cathedral, though the author is unknown. It covers the history of Danish kings from AD 826 to AD 1143 and was the first of its kind.

Interestingly for us, it also mentions Lothbrok and his sons. Since this is not a saga or Old Norse poem, it is much more focused on the actual facts. Furthermore, the priest writing the chronicle is writing it from a Christian point of view. Although seemingly staying true to historical facts, the heathen vikings were the evil barbarians attacking the good Christians in England and continental Europe.

However, and that is a big caveat, the dates or years used, or implied in the text doesn’t always add up with what we know today. As such, some events are out of order chronologically. When reading it, I have chosen to disregard any confusion with the dates. Instead I look at what it does in fact share about Ragnar Lothbrok (not much) and his sons (much more).

What we learn from the Roskilde Chronicle

Maybe the first and one of the most interesting conclusions we can draw from this is based on the fact that Ragnar Lothbrok is not mentioned as a Danish king. Seeing as the book starts in AD 826 he should have been in there if he indeed was one. Neither are any of his sons listed as kings of Denmark at any time after Ragnar’s death. This might have slipped his mind though, as we will see in the next Danish chronicle.

However, his son Ivar the Boneless is apparently a king somewhere, as he calls on all the kings of the Norsemen, also the Danish king(s) to join him in an attack on England. The great coalition of vikings under different kings is the one which is also known as The Great Heathen Army.

According to Anglo-Saxon sources it landed in England in AD 865 and wreaked havoc up and down the East Coast of England. In AD 867 the vikings to the city of York, and largely unopposed, harried the other towns and cities across the north and east of England.

Notably, in the chronicle Ivar’s brothers are listed as Ingvar (likely a case of mistaken identity and referring to Ivar himself), Bjørn (Ironside), Ubbe and Ulf (unknown who this would be).

Some of their acts are also detailed, besides capturing York in AD 867. Two or three years later (no time is given in the chronicle itself) they met and beat the forces of King Edmund of East Anglia. Then, according to the chronicle, King Edmund (later known as Edmund the Martyr), was captured, tied to a tree and whipped in order for him to renounce Christianity. Refusing to do so, at least according to the chronicle, he was then shot with arrows and beheaded.

The Chronicle of Sven Aggesen

A second Danish chronicle from the late 12th century, also aimed at collecting the history of Denmark from its early beginning. Written by a Dane named Sven Aggesen, a direct descendant of Danish hero Palnetoki (five or six generations removed) who founded the legendary Jómsvikings.

Sven Aggesen was educated in Frankia and notes in his writing that he found great joy in reading books about history and older kings. He might have been reading about both old Frankish kings as well as Roman history as he was well versed in Latin.

In writing the Brevis historia regum Dacie (Short history of Danish Kings), he tried to cover the whole span of the Danish nation from around AD 300 to AD 1185. There are few dates or years found in the chronicle, but rather it lists kings he is familiar with in sequence.

While rather sparse on any details about Ragnar, he is mentioned as the father of a Sighwarth, obviously being Sigurd.

Sigurd takes the Danish Throne

“After this Sighwarth, the son of Regner Lothbrogh, invaded the kingdom of Denmark; having joined battle with the king, he killed the king and gained the kingdom. And while he was in possession of the conquered kingdom he took to his bed the daughter of the slain king.”

By this account, Sigurd took Denmark and married the previous king’s daughter, legitimizing his claim to the throne as well. This story can also be said to confirm that Ragnar was never believed to have been a king of Denmark. At least not by Danish historians writing in the 12th century about Danish kings.

Interestingly, both this chronicle and the previous one were written in Denmark, a full hundred to two hundred years before the Icelandic sagas about Ragnar and his sons were written down. However, both the chronicles and the later Sagas must have drawn from some of the same sources.

There Is no question that even though shrouded in the mist of time, Ragnar Lothbrok and his sons were very much alive and well in the near history of more or less contemporary sources.

Saxo Grammaticus Gesta Danorum

The third and last Danish chronicle I am including here is Saxo Grammaticus’ collection of books called Gesta Danorum. Written sometime in the late 12th to early 13th century by a Danish historian, likely from a notable family, judging by his education and fluency in Latin. Interestingly, Saxo knew Sven Aggesen well, and Saxo knew Aggesen’s work well.

Saxo was encouraged to write the books by the archbishop Abselon, the highest representative of the Catholic Church in Denmark at the time. Saxo writes himself that his goal was to write of Danish heroes “to glorify our fatherland“. Styling the books on ancient Greek classics like Virgil’s Aeneid, Saxo seems to have embraced the glory and lore, more than strict historical facts.

According to Saxo, Ragnar is the son of legendary viking chieftain Sigurd Hring, king of Denmark. Hiring is killed in battle over the throne and the young Ragnar is sent into hiding among friends in Norway. Then still quite young he manages to take back the throne of Denmark, and shortly after also takes the Swedish throne.

However, and here I have to admit I might be missing something, according to Saxo, Ragnar takes the Swedish throne, but a few years later someone else is king of Sweden without there being any explanation for this. This kind of inconsistencies are found all through Saxo’s writing about Ragnar. This shift on the Swedish throne happens during three years when Ragnar is living in Norway. He went there to avenge the murder of his grandfather, and battles a Swedish king named Fro. This part of the story seems to be wholly made up, and possibly to many people’s dismay, it is also here we are introduced to Ragnar’s supposed first wife, Lagertha.

Meeting the Shieldmaiden Lagertha

When Ragnar went to Norway to avenge his grandfather, he was joined in battle by a group of women warriors. Saxo likens them to Amazons, the legendary all-woman warrior tribe in Greek mythology. Foremost of all the women warriors, fighting at the front was a fierce woman with flowing blonde hair. After the battle was won, Ragnar was set on finding out who she was, learning her name was Lagertha.

Saxo being a Christian man from the Catholic Church in the early 13th century must have surely thought this was quite a remarkable tale. Just imagine, unmarried women running about, fighting like men. In some ways you can see parallels from the ancient Greek story of Ulysseus, meeting the Amazones on his travels.

Breaking from the previous Danish chronicles, Saxo goes into great detail about the many deeds of Ragnar. All across the European continent. Winning battles and conquering lands from Finland in the north, to the British Isles in the west all the way south to Rome itself.

How Ragnar met his end according to Saxo

Interestingly, and a strong indication that both the Icelandic and Norse sagas and the Danish chronicles drew from the same sources, there are many striking similarities in the stories. When looking only at the different Danish, Christian sources the two chronicles discussed before are more factual and seemingly trying to be historically accurate. Saxo on the other hand writes more freely, mixing myth, lore and facts. In doing so, Saxo is more aligned with the Old Norse sagas.

One recurring theme in these more mythical accounts of Ragnar’s life is how he dies in a pit of venomous snakes after a failed attack on England. Also the line about how the little piglets would react to knowing how the old boar met his end is found here.

For when he had been taken and cast into prison, his guilty limbs were given to serpents to devour, and adders found ghastly substance in the fibres of his entrails. His liver was eaten away, and a snake, like a deadly executioner, beset his very heart. Then in a courageous voice he recounted all his deeds in order, and at the end of his recital added the following sentence: “If the porkers knew the punishment of the boar-pig, surely they would break into the sty and hasten to loose him from his affliction.”

The Danish authors clearly knew of each other, at least to some degree, and possibly borrowed ideas among their writing. However, I don’t think that the Danish chronicles were informing the Icelandic and other Old Norse writers when they wrote down the sagas and various poems fifty to a hundred years later.

Likely, their sources were much older, and existed deep in the lore of Old Norse history.

The viking king Ragnar raiding Frankia and Paris

When researching the life of Ragnar, I have found that hard facts and dates etc. are more likely to be found in sources of the victims. That is to say, the Frankish empire and the Anglo-Saxons in England. They were more literate at the time and kept records of events, often these were raids by the heathen barbarians.

In the middle of the 9th century, the great European power was the Frankish Empire. Especially during the reign of Charlemagne from AD 768 – 814, the empire grew to cover most of continental Europe.

To the south, their borders were against the Emirate of Córdoba, an Arabic kingdom covering most of Spain and Portugal, and in the south of Italy, towards Byzantium, or the East Roman Empire. Towards the east the empire came up against various tribes in modern day Eastern Europe, and The Kyivan Rus, basically the “Eastern Vikings”. To the west, the different kingdoms on the British Isles were to a large degree politically and religiously aligned with the Franks.

To the north, there was a troublesome group of petty kings spread across modern day Scandinavia, the heathen Norsemen. Interestingly, the Frankish Empire never managed to take Denmark, which is like an extension of continental Europe.

Ragnar Sacks Paris

After the Frankish ruler Charlemagne died in AD 814, his Empire was inherited by his sole son Louis. However, when Louis died in AD 840, it led to a time of civil war as his three sons battles over the empire. This ended more or less in AD 843 when the Frankish Empire was divided into three different parts.

In this post civil war climate, with a once imposing empire divided into three smaller parts, the path was wide open for outsiders to take advantage. A major such attack happened in AD 845, as a large flotilla of more than a hundred viking ships came up the river Seine. The river winds its way from the English Channel deep into France, and about 220 miles from the coast was the city of Paris.

According to contemporary Frankish annals, the vikings were led by a king named Ragnar, last name not mentioned. From the contemporary Annals of Saint Bertin, written down in or right after AD 845.

“The harshest winter. A hundred and twenty ships of the Normans, in the month of March, along the Seine, ravaging everything here and there, Lutetia of the Parisians*, without any resistance at all.”

*the Latin name for Paris.

Like Rollo of Normandy Ragnar Was Offered Land

The same Ragnar, had been given land as an attempted pay-off in a part of modern day Belgium in AD 841. However, that truce had not held and the Frankish emperor and Ragnar obviously had a falling out.

Interestingly, this is almos the exact same story that would play out many years later. Contrary to what many believes, the famous viking chief Rollo was not the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok. Rollo was in fact a Frankish name for the Norwegian Hrolf Ragnvaldsson. However, Rollo did unsuccesfully try to sack Paris in AD 885-886. After another failed siege of a town, Rouen in Francia in AD 911, Rollo was offered land and a truce agreement.

Hrolf Ragnvaldsson accepted the truce agreement, and became Rollo the Duke of Normandy, the first of the Normans.

From all the viking raids across the divided Frankish empire it’s clear they were a force to be reckoned with. They were also at times aligned with one or another of the different rulers, playing a part in the internal power struggles of the Franks.

Lothbrok mentioned as the father of Ivar and others

Regrettably, at least when my goal is to research the life of Ragnar Lothbrok, his sons come up even more frequently in contemporary sources. However, the mere fact that they do, and are described as “sons of Lothbrok” would point to Ragnar Lothbrok being a known entity in the Frankish and Anglo-Saxon world.

In another important manuscript written by Adam of Bremen in the second half of the 11th century, Ragnar and his sons are mentioned.

“The names of the Danish kings in his time are not recorded in his Gesta. In the History of the Franks we read that Sigefrid ruled with his brother Halfdan. They also sent gifts to the Caesar Louis, namely, a sword with a golden hilt and other things, and asked for peace. And when mediators had been sent by both parties to the Eider River, they swore to a firm peace on their arms, according to the usage of the folk. There were also other kings over the Danes and Northmen, who at this time harassed Gaul with piratical incursions. Of these tyrants the most important were Horic, Orwig, Gotafrid, Rudolf, and Ingvar. The most cruel of them all was Ingvar, the son of Lodbrok, who everywhere tortured Christians to death. This is written in the Gesta of the Franks.”

From this passage, the two Danish kings mentioned, Sigefrid and Halfdan, are likely Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, and his brother Halfdan. One of the other Danish kings mentioned, Ingvar, is Ivar-the-Boneless.

Personally I feel that it’s quite remarkable that the Franks were able to gather as much information and names as they did. To a large part they didn’t speak the same languages, and with the multitude of viking chieftains raiding both the Frankish Empire and the kingdoms of Britain, they were fairly well informed.

Ragnar and his sons in Britain

Like so many Viking Age chieftains before and after him, Ragnar came to desire the throne of all the kingdoms on the British Isles. This much, the different Sagas and outside sources pretty much agree upon. However, just what motivated him, and how it ended is shrouded in a deep fog of time and myth.

In the old sources from Britain and the Franks, describing events in Britain, it is the sons of Ragnar who are mentioned. I will be exploring the lives and tales of Ragnar’s sons in separate posts, and I will also do one on “The Great Heathen Army” which is what the Christian Brits called the viking campaign across England and the British Isles in AD 851 well into the AD 870s.

Suffice to say, several of Ragnar’s sons are mentioned in contemporary sources, and in some of them they are said to be sons of Ragnar, or of Lothbrok.

However, there are no records of an attack by Ragnar Lothbrok, on the petty king Ælla where Ragnar was captured and killed in a snake-pit.

The closest we come to that is described in the Asser’s Life of King Alfred. It is a biography of King Alfred written in AD 893 by a Welsh monk named Asser.

The vikings and the battle for the city of York

Relying mostly on what had been written in the Saxon Chronicle for the year AD 866 and AD 867, Asser describes the vikings attack and capture of York. Although in the account below it seems the vikings attacked the city that year, they had actually already taken the city the year before, on November 1st, AD 866. They were likely quite settled when the Northumbrians attacked them on a Friday, March 21st, AD 867, just a week or so before Easter that year.

Interestingly it is somewhat colored by the religion and politics of the time. Asser seems to think that the Northumbrians brought this upon themselves. He mentions them having disposed of a petty king Osberth (likely aligned with Alfred), and instated another instead, named king Ælla. In the ensuing year, Osberth and Ælla manage to set aside their differences and unite in an attempt at ousting the heathens from York.

Life of King Alfred, Ch. 27. Defeat of the Northumbrians.

—At that time a violent discord arose, by the instigation of the devil, among the Northumbrians, as always is wont to happen to a people who have incurred the wrath of God. For the Northumbrians at that time, as I have said, had expelled their lawful king Osbert from his realm, and appointed a certain tyrant named Ælla, not of royal birth, over the affairs of the kingdom.

But when the heathen approached, by divine providence, and the furtherance of the common weal by the nobles, that discord was a little appeased, and Osbert and Ælla uniting their resources, and assembling an army, marched to the town of York.

The heathen fled at their approach, and attempted to defend themselves within the walls of the city. The Christians, perceiving their flight and the terror they were in, determined to follow them within the very ramparts of the town, and to demolish the wall; and this they succeeded in doing, since the city at that time was not surrounded by firm or strong walls.

When the Christians had made a breach, as they had purposed, and many of them had entered into the city along with the heathen, the latter, impelled by grief and necessity, made a fierce sally upon them, slew them, routed them, and cut them down, both within and without the walls. In that battle fell almost all the Northumbrian troops, and both the kings were slain; the remainder, who escaped, made peace with the heathen.

What to make of the Battle of York

In the Vikings series, and the Icelandic Sagas, the story is that the sons of Ragnar gather an army and attack Northumbria to avenge the death of Ragnar Lothbrok. Based on the evidence, or lack thereof, it is impossible to ascertain the truth of this.

However, there are some facts that are interesting. The Viking raids on Britain had been going on for almost a century by the time Ragnar’s sons and the Great Heathen Army took York. There are mentions of Lothbrok several times in old British and Frankish sources, often mentioned in a way which makes it seem he was a known figure.

In AD 865, the year most people point to as Ragnar’s likely year of death, Ælla was the king of Northumbria. It was also a time of strife, with different parties warring over the throne there. Vikings were known to often take part in conflicts like that, either playing different sides against each other, or aligning with one side. It is not inconceivable that Ragnar Lothbrok would have done just that, if he had landed in this turmoil before or in AD 865.

If he then aligned with king Osbert, the previous king opposing king Ælla, he would likely have been on the losing side. While there are no contemporary mentions of a snake-pit, one could argue that the Christian writers of the time would likely have been inclined to gloss over any questionable or atrocious behavior on their side. They were quite eagerly representing a narrative of good fighting forces of evil, ie. the heathens.

Whether or not this was what motivated the sons of Ragnar to invade we might never know. In a time of internal conflict it did present itself as a great opportunity for an attack either way.

Annals of Saint Neots and the Daughters of Ragnar

The Annals of Saint Neots is a shorter work, at some times also attributed to Asser. However the true author has been questioned and today it is believed to have been written much later, but building upon Asser’s writing among others.

When comparing it to Asser’s The Life of King Alfred, you soon recognize that some parts are quite identical, only expanded upon. One such expanded section is found regarding the year AD 878. This year saw a lot of action, and a major battle at Cynwit, somewhere in the southwest of England.

This was years after the death of Ragnar, but adding to his story is a mention of a Raven banner, carried by the Vikings. In the Annals of Saint Neots version, expanding upon what Asser wrote, we learn who was said to have sown the banner. Even what magical qualities it had.

“…standard called Raven; for they say that the three sisters of Hingwar and Hubba, daughters of Lodobroch, wove that flag and got it ready in one day.”

Based on this one mention, which is somewhat questionable, it seems Ivar and Ubba had at least three sisters. I am including the whole section below.

Extract from the Annals of Neots for the year AD 878

In the same year the brother of Hingwar and Halfdene, with twenty-three ships, after much slaughter of the Christians, came from the country of Demetia, where he had wintered, and sailed to Devon, where, with twelve hundred others, he met with a miserable death, being slain while committing his misdeeds, by the king’s servants, before the castle of Cynuit, into which many of the king’s servants, with their followers, had fled for safety.

The pagans, seeing that the castle was altogether unprepared and unfortified, except that it had walls in our own fashion, determined not to assault it, because it was impregnable and secure on all sides, except on the eastern, as we ourselves have seen, but they began to blockade it, thinking that those who were inside would soon surrender either from famine or want of water, for the castle had no spring near it.

But the result did not fall out as they expected; for the Christians, before they began to suffer from want, inspired by Heaven, judging it much better to gain victory or death, attacked the pagans suddenly in the morning, and from the first cut them down in great numbers, slaying also their king, so that few escaped to their ships; and there they gained a very large booty, and amongst other things the standard called Raven; for they say that the three sisters of Hingwar and Hubba, daughters of Lodobroch, wove that flag and got it ready in one day.

They say, moreover, that in every battle, wherever that flag went before them, if they were to gain the victory a live crow would appear flying on the middle of the flag; but if they were doomed to be defeated it would hang down motionless, and this was often proved to be so.

What we can reasonably say we know about Ragnar Lothbrok

There are a few other mentions of Ragnar Lothbrok as well, but not that I feel adds to the story and background I have tried to lay out here. When trying to discern what is right or not, I am of the opinion that the easiest explanation is often the most believable.

While the sagas and other Old Norse sources tend to have a very fluid mix of myth and historical facts, the Danish, British and Frankish chronicles are more factual.

One inescapable fact I feel most people should agree upon is that Ragnar Lothbrok was clearly a historical person, alive and well sometime in the 9th century. There are far too many mentions of him, and other historical people connected to him for him to be just a myth.

How Ragnar got the name Lothbrok ‘Shaggy Breeches’

Being the son of Sigurd Hring, Ragnar grew up being named Ragnar Sigurdsson. However, most mentions from both sagas and contemporary sources know him as Ragnar Lothbrok.

Lothbrok is the anglicized form of the Old Norse loðbrók, where loð means hairy or shaggy, and –brók means breeches, which are like a ¾ length pants of the time.

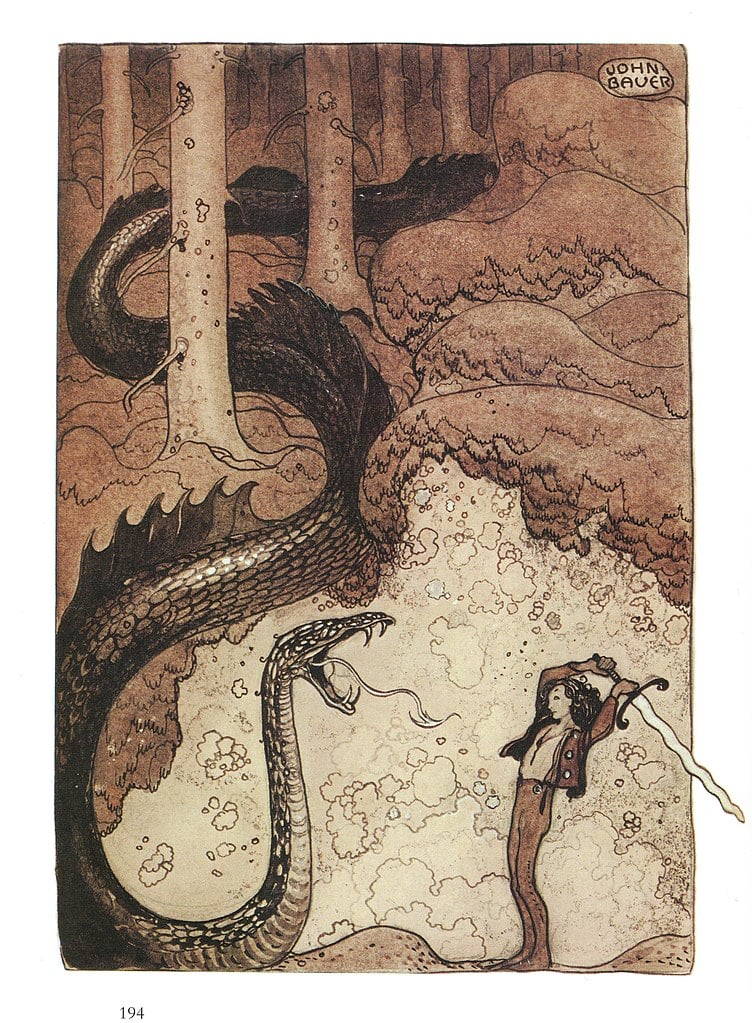

Legend has it, based on the Icelandic sagas, other Norse poems and Saxo Grammaticus version, he earned the name when he fought a giant lindworm to win Thora’s hand.

She had been given a small snake as a pet by her father who had found it in the forest one day. Unknown to the king, the small snake was actually a magical lindworm, a sort of forest serpent, or dragon.

As the dragon grew, so did a hoard of gold it was lying on top, jealously guarding. In the end the vicious, poisonous dragon became a problem, and the king promised both the gold and his daughters’ hand in marriage to anyone who could kill it.

This story reached Ragnar, and he devised a plan for how he would defeat the dragon without being killed by it or its poison. He had made some new clothes, especially for this, a thick fur coat and a pair of hairy, or shaggy breeches.

Ragnar kills the dragon and wins Thora’s hand

Then the sources vary a bit, with Saxo having a version unique to him. Most sources agree that he had his coat and breeches boiled in tar and then rolled in sand on the beach before going to face the dragon.

However, according to Saxo he wetted the clothes in the ocean, and let them freeze before going to meet the dragon. This version of events makes little sense though, as much as I am inclined to believe this mythical part of his story. Imagine trying to move, let alone fight a lethal dragon in an attire wholly frozen, you would be quite immovable.

Either way, Ragnar managed to kill the giant serpent, and in the end he won all the gold and the hand of Thora in marriage. With the victory also came his new name, Ragnar Lothbrok.

Interestingly, his future wife Aslaug’s father was the legendary viking hero Sigurd-the-Dragonslayer. As such, this story of Ragnar also killing a dragon might have been created to make him too a dragon slayer. Either way, the name really stuck so the backstory must have been widely known.

Family of Ragnar Lothbrok

Ragnar was the son of a Swedish petty king named Sigurd Hring. His mother’s name is less certain, but could be Åsa according to one saga. After the Battle of Brávalla, it might be that Hring also became the king of parts of Denmark,

Ragnar’s Wives

First he was married to the shieldmaiden Lagertha, when he was still a teen, or in his early twenties. According to Saxo (and only him), they lived together in Norway for around three years. The biggest problem with Lagertha is that she isn’t attested to anywhere else. Being described as an Amazon or Valkyrie-like warrior, that seems unlikely to be something the Icelandic skalds would have skipped if they were aware of this story.

His second wife was Thora Borgarhjort, daughter of the Swedish petty king Herraud. This is a more commonly told part of the lore about Ragnar Lothbrok as it also explains how he came by that name. Before what happened when Ragnar tried to win Thora’s hand, he was likely just known as Ragnar Sigurdsson, ie. son of Sigurd (Hring).

Thora however, was basically a captive, living in a house with a giant serpent coiled around it. The snake, or dragon, had started out as a small pet snake in a box, but grew into a monster, encircling her home. Being a magical creature, it also guarded a large hoard of gold treasure, which grew as the dragon grew. Ragnar defeated the snake and won the gold and Thora’s hand. Sadly, Thora dies after only a few years, leaving Ragnar with two sons.

Ragnar’s third and last wife was Aslaug, daughter of the legendary Sigurd Fafnesbani and the Valkyrie Brynhildr. However, when they first met she said her name was Kraka and that she was the daughter of poor peasants.

The Sons and Daughters of Ragnar

The sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, at least some of them, are easier to find mentioned in sagas and contemporary sources. However, Ragnar didn’t only have sons, he had several daughters as well, two to five, depending on the source.

Children of Lagartha and Ragnar

When it comes to Lagartha and their children, we only have the one work by Saxo Grammaticus as a source. According to Saxo, Lagartha and Ragnar had three children, two daughters whose names are lost, and one son named Fridleif. What became of them after Ragnar left Lagartha after three years is not known. However, according to Saxo’s account, when Ragnar left to face the dragon guarding Thora’s house, he had his men swear to follow Fridleif, which would indicate that he had not entirely left them behind.

Children of Thora and Ragnar

Much like his children with Lagartha, Ragnars’ children with Thora never played large roles in the sagas and they don’t show up in any sources outside of the Old Norse sagas and poems.

Referenced in the various Old Norse sagas and poems, Thora and Ragnar had two sons, Eirik and Agnar. And as Fridleid seems to have been an invention of Saxo’s, the two are said to be Ragnars’ oldest sons, and second to him only. Apparently living well into their adulthood, they took to raiding together with their brood of younger half-brothers from Aslaug and Ragnar.

Then, one summer Ragnar is away in the Kievan Rus, the two brothers seem to conspire to take Sweden and hold it against their father Ragnar. In the end though, Eirik is killed in the battle, and Agnar, mourning his brother, chooses to be killed on the battlefield in order to join him in death.

Children of Aslaug and Ragnar

The sons of Ragnar and Aslaug are mentioned extensively in both the sagas and many contemporary sources. However, there are some small discrepancies of just how many children they had.

According to both the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, and the Tales of the Sons of Ragnar, they had four sons. However, the sagas only agree on the name of the first three of them, Ivar Boneless, Bjørn Ironside and Hvitserk.

According to the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, their fourth and last son was named Ragnvald, but in the Tales of the Sons of Ragnar, he is named Sigurd. That is the boy with the mark like a snake in the eye.

However, from other sources it’s clear that the son called Hvitserk, meaning White-shirt, really was named Halfdan, and his nickname was Hvitserk. He would later become one of the leaders of the Great Heathen Army, along with Ivar Boneless, and also king of both York as well as ruler of London.

There is also a famous king Ragnvald Heidumhære who lived in the 9th century. His ancestry is unclear, but he could be the mentioned son of Aslaug and Ragnar.

Finally, based on various Anglo-Saxon accounts, there was another son of Ragnar, who was part of the Great Heathen Army named Ubba, or Ubbe. He goes largely unattested to in the Old Norse sagas and poems, but receives several mentions in more or less contemporary Anglo-Saxon chronicles.

When you take into account the contemporary sources as well as the Old Norse sagas, Aslaug and Ragnar had at least five, maybe six sons, namely; Ivar Boneless, Bjørn Ironside, Halfdan/Hvitserk, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, Ragnvald and Ubba. Then they also had at least three daughters, names unknown, however this is based solely on the Annals of Neots.

The Life and Exploits of Ragnar Lothbrok

The truth of the matter is that there is little actual evidence of most of the events associated with Ragnar Lothbrok. From his early years, we only have the Old Norse sagas and Saxo Grammaticus recounting what happened. They are not really based on much that one can easily verify. Neither is Ragnar Lothbrok mentioned as a king in any of the lists and stories of Norse viking king genealogies.

Flipping this around though, there is an abundance of stories about him, like the two major sagas, the Krákumál poem and mentions in other Old Norse poems. So many in fact that to me it seems obvious he existed. Also, while the many stories are rife with supernatural elements, it seems likely that core elements are true.

Early years

The sagas and Saxo Grammaticus can not quite agree on whether Ragnar’s father Sigurd Hring was a petty king in Sweden or Denmark, but most point to Sweden.

The sagas don’t go deep into the circumstances surrounding Sigurd Hrings death. However, it might have been as a result of a power play for the kingdom which he ruled. From Saxo (not mentioned in the Sagas) we hear that Ragnar was hidden away in Norway at a young age, some time before, or just after his father died.

A little later, he seems to have taken, or been given the throne of that part of Denmark after his father, this isn’t really explained. Then, according to Saxo, he goes to Norway to free some women who have been put in a brothel who are his kin by his maternal grandfather. In this fight, which turns into a small battle, he meets the shieldmaiden Lagartha.

Ragnar wins Lagartha’s hand

Ragnar quickly falls for the fierce warrior maiden, but she is not immediately taken in by his charm. Instead of them marrying right away, she sets up some demands, but agrees to meet him at her house. In what seems like a bit of a trap, Ragnar is met by a fierce bear and a large dog guarding her house when he comes to meet her.

However, he kills the bear with a spear and strangles the dog, and having proven himself to her, wins her hand as well. This leads to what seems to be three calm years, living in Norway, married to Lagartha.

Ragnar starts raiding and marries Thora

Again leaning only on Saxo’s version, Ragnar leaves Norway to strike down a challenge to his Danish throne by some other Danish petty king. This is also where Saxo and the two main Ragnar Sagas’ become more aligned.

Having left Norway behind, and being out in battles and on raiders, it seems Ragnar has solidified a position as a petty king in both Denmark and part of Norway. Word reaches him about a fair maiden trapped in a house, being guarded by a magical dragon. Daughter to the local Earl or king, the maiden’s name is Thora.

This story, as I went through it earlier, is what earned Ragnar his nickname Lothbrok, or shaggy/hairy breeches. It also led to him divorcing, or just plain leaving Lagartha, and marrying Thora. Together they had two sons, Eirik and Agnar, but sadly Thora died shortly after they were born.

Ragnar meets the poor farmer girl Kraka

This again depends a bit upon which version of the story one follows, but in broad strokes, Thora dies and Ragnar happens to meet a new woman who calls herself Kraka. She is the daughter of a pair of poor peasants in Norway, but doesn’t look like them. In the fashion of many Old Norse poems, it is discussed how down right ugly the poor peasants are, and comparing them to their daughter.

Kraka is a truly beautiful woman and Ragnar lets it be known early on that he would like to marry her. However, just like Lagartha was slow to accept his courtship, Aslaug doesn’t immediately accept. Instead there are some back and forth with a riddle and a period of waiting. In this story too, a dog is involved and is killed so this seems to be a returning theme.

After having done his part, Kraka finally agrees to come to him, but she says they should wait three nights to consummate their marriage. The peasant women had apparently prophesied that their child would be deformed unless they waited three days. Ragnar however is not inclined to wait, and some time after, Ivar the Boneless is born.

The absent Ragnar is away raiding

After having married Kraka, it turns out she is really named Aslaug, and is the daughter of the legendary Sigurd Fafnisbani, killer of the dragon Fafnir, and the valkyrie Brynhildr. They have several children, but in both the sagas and Saxo’s version, Ragnar is largely away on raiding campaigns as the sons grow up.

In this period, according to Ragnar himself in Krákumál, he successfully raids and battles all across continental Europe. Doing battle from the Kievan Rus in the east to Paris in the west and all the way down to Rome in the south, Ragnar is hugely successful.

As I already described, some viking king named Reginherus (ie. Ragnar) successfully raided Paris in March AD 845. The meek ruler of the Western Frankish Empire at the time agreed to pay him off with more than two tons of silver and gold.

The Sons of Ragnar and Britain

Back home in Denmark, his sons grow weary of not accomplishing anything great themselves, and this first leads to his two oldest sons Eirik and Agnar (Fridleif is out of the picture) going to Sweden. There it seems they are intent on taking Sweden, or some part of it, for themselves, actually defying their father Ragnar. This all ends in tragedy as Eirik is killed in battle, and Agnar chooses to be killed on the battlefield in order to join his brother.

These events first lead the four (or five) half-brothers of Eirik and Agnar to go to Sweden to avenge their fallen brothers. Remarkably, Aslaug leads a large force of men, also going to the battle, but coming over land, the brothers going by sea. This distinction is made about her leading men on horse, but to be pedantic, they would all first have to get on ships to cross from Denmark to Sweden.

This successful endeavor seems to be the start of the brothers going on more and more successful campaigns around on the European continent. Historically, this is a time in which there are a lot of conflicts, raids and smaller battles between the heathen Danes and their Saxon, Frisian and Christian Franks to their south.

Not content to just bask in the glory of his successful sons, Ragnar, who would have been an older man at this time, set his eyes on an even bigger prize, England. At the time, England was divided into four smaller kingdoms, Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia and Wessex. I believe Wessex, in the south-west, was the strongest and possibly richest. Northumbria on the other hand, being in the north-east, was the kingdom closest to the raiding vikings from Scandinavia.

The Death of Ragnar Lothbrok

Set on proving that he could still out-shine the exploits of his sons, Ragnar decided to go on an attack on England in AD 865. It is in this raid that things don’t at all go as planned, and Ragnars army suffers defeat in the battle of York.

According to Old Norse sources like the sagas and the Krákumál Ragnar is captured by the king of Northumbria, Ælla. However, as horrible as Ragnar’s death is, it is worth mentioning that it is not at all mentioned in any of the actual contemporary sources.

In the classical story, Ælla has Ragnar Lothbrok thrown into a snake-pit. First the snakes will not bite him, this is because of a tightly woven silk shirt Aslaug has made him. However, he is stripped of it, and soon the snakes bites him repeatedly, eventually killing him.

“The young pigs would now squeal if they knew what the older one suffered.”

Thus, just as he foretold there lying in the bottom of the pit with the snakes, his sons are enraged and set out to take a bloody revenge. Setting in motion the story of the Heathen Army campaigning and the sons of Ragnar taking large parts of England in the process.

Awesome this was thank you for all your work!

Thx Michael, much appreciated!