Harald Sigurdsson (Old Norse Haraldr Sigurðarson) is popularly known as the last viking king. That’s not to say he wasn’t succeeded by his sons, but no one ever really followed in his footsteps.

He would later in life be known as Harald Hardrada (Old Norse Haraldr harðráði) meaning hard, or strict ruler. However, and this is where some might feel he is “less” viking than some earlier viking kings, Harald was Christian.

He is otherwise the prototype of all things one would envision hardcore viking warrior poets of the time to be. He fought the legendary battle of Stiklestad, where King Olaf II of Norway was killed. Later he would himslef die in the Battle of Stamford Bridge. In between those great battles, he commanded the Byzantine Varangian Guard, married a Kievan Rus princess, and engaged in other battles across Europe.

Harald Hardrada was certainly not a man to shy away from conflict, in return he got the princess and became maybe the richest of all viking age kings. This is his story, as best I am able to put it into words.

TL;DR – Short Facts

Harald Sigurdsson was born in the south of Norway to petty king Sigurd Syr and Åsta Gudbrandsdatter in 1015. Through their shared mother, he was the younger half-brother of Olaf Haraldsson, later king Olaf II of Norway.

He fought at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030 where Olaf II lost his life, and Harald fled Norway. Welcomed around a year later at the court of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise, ruler of the Kievan Rus Empire.

After two or three years joining Prince Yaroslav in several battles, Harald and his men traveled to Byzantium. There he would rise through the ranks to become the leader of the Varangian Guard. He left the Middle East after falling out with the Byzantine empress Zoe in 1042, going back to Kievan Rus.

There he married princess Elisiv, and together they left for Norway in 1045. Wanting to claim the Norwegian throne, he joined forces with an ousted Danish noble and a Swedish king. After a campaign of raiding, in 1046 Harald reached an agreement with king Magnus the Good (illegitimate son of Olaf II, so his nephew) to rule over Norway and Denmark jointly.

After Magnus’ death in 1047, Harald became sole ruler of Norway, and declared himself king of Denmark as well. In Denmark however, Sweyn Estridsson (King Sweyn II of Denmark) had taken the throne. This resulted in almost twenty years of conflict, with numerous short, but violent raids. Lasting until 1064 when they reached a peace agreement.

Eying the throne of England, in 1066 Harald joined forces with Tostig Godwinson. He was the brother of the newly proclaimed king of England, Harold Godwinson. Their adventure ended at the Battle of Stamford Bridge where Harald lost his life, likely fifty one years old.

Early Life and Family Tree

Harald Sigurdsson was born in 1015, in an inland region of Norway known as Ringerike, Old Norse Hringaríki. While he is best known today as Harald Hardrada, his name at birth was Harald Sigurdsson, (Old Norse Haraldr Sigurðarson). Later in life he would pick up the epithet Hardrada, (Old Norse harðráði), meaning Hard, or Strict -ruler.’

Haralds’ father was Sigurd Syr, the local king, or chieftain, and his mother was Åsta Gudbrandsdatter, her second marriage. From a previous marriage with another petty king, Åsta had several sons, chief among them, Olaf Haraldsson. Haralds older half-brother Olaf would later become king Olaf II of Norway.

Haralds father was rich and powerful, occupying a part of modern day Norway rich in farming. In 1016, when Harald was only a year old, his older half-brother Olaf became king of Norway. With his own father a petty king, and his half-brother, the king of all of Norway, Harald must have had a privileged and interesting upbringing.

King Olaf was Christian and he was, to put it mildly, quite determined to encourage others to accept the faith. Harald grew up with his two older brothers on Sigurd Syr’s estate. However, the sagas describe Harald as looking up to, and taking after king Olaf, more than his brothers.

Harald Sigurdsson’s Wives and Children

Although less tumultuous than the intriguing affairs of the Byzantine court, Harald would also have some interesting affairs. The thing is, according to the Heimskringla, he had two wives at the same time. Not an affair, but a second wife, although she was not called queen.

For a devout Christian, that would have been somewhat of a challenge. However at the time, and as a king with pagan roots, it wouldn’t have been so out of the question.

After his return from service in Byzantium he married Elisiv of Kiev, (Elisaveta) daughter of prince Jaroslav of Kievan Rus. This was likely in 1044-45. Harald had written poems to her during his service in Byzantium so clearly the flame had awoken much earlier.

They would go on to have several children, where two daughters are known, Ingegerd and Maria.

Still, according to Heimskringla, he also married a woman named Thora Thorbergsdottir, daughter of Thorberg Arnason. Although she was not recognized as “the” queen, she would have two sons by Harald who both would grow up to be kings of Norway.

Keeping it all in the family, Thora’s brother Eystein was promised the hand of Harald and Elisiv’s daughter Maria. After the events in 1066 though, that would never come to pass. Both king Harald and Eystein died at Stamford Bridge. Furthermore, Maria is said to have died the same day, although far away in the Orkney islands.

Harald and Thora also had several children where at least two are known, Magnus, later king Magnus II, and Olaf, later king Olaf III.

There might certainly have been affairs outside of these marriages, but no possible children from these are known.

Battle of Stiklestad and Exile

In 1028, when Harald was around thirteen years old, his half-brother Olaf II was ousted as king of Norway. This came after a revolt among several Norwegian petty kings, supported by Cnut the Great, king of Denmark and England. Olaf II was viewed rather unfavorably by some of the smaller local kings and after facing off with them and King Cnut, he had to flee to Kievan Rus.

At the time, in the beginning of the 11th century, Norway had gone from a number of petty kingdoms, to being more or less successfully combined under one king. With Olaf chased out of Norway, king Cnut of Denmark and England, had installed Earl Håkon Eiriksson as regent of Norway. In 1029 Håkon Eiriksson was lost at sea, and with no one on the throne, Olaf made a comeback.

He marched from Sweden into Norway towards Nidaros which was the capital at the time, close to the middle of the country. On the way, he was met by Harald and several hundred men King Sigurd and Harald had raised from their region.

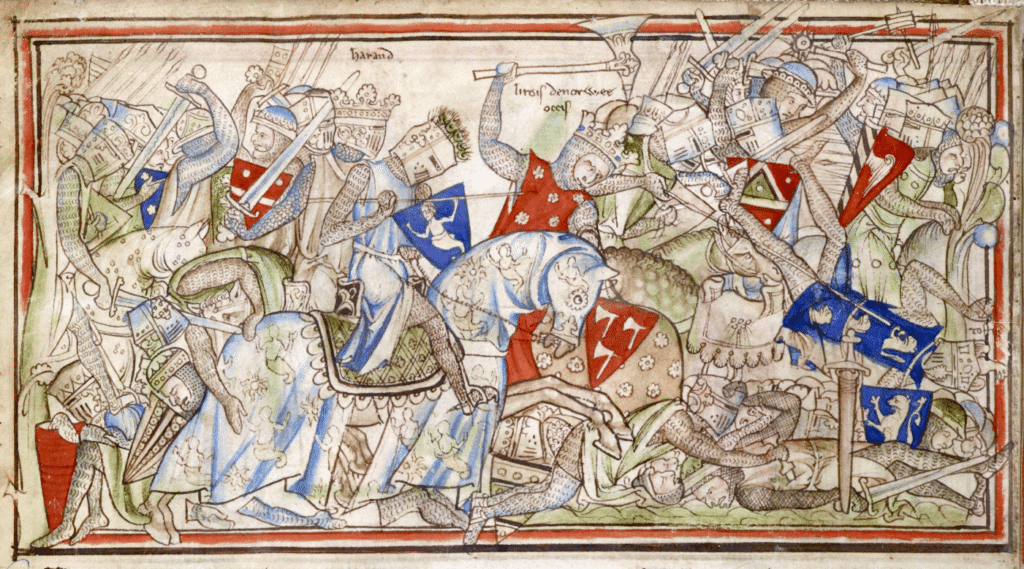

July 29th, 1030 Olaf’s army of Swedes, Icelanders and Norwegian followers met a “farmers army” led by local chieftains. Most likely the majority of people on both sides were Christian. As such, this was a battle for the throne of Norway, more than any ideological fight.

In the ensuing battle, Olaf II was killed, possibly by a famous chieftain named Tore Hund. Olaf had had Tore Hund’s nephew killed some years before while he was still king. The Battle of Stiklestad was really one where old scores were settled and with some deep animosity between the opposing forces.

Harald Escapes to Sweden and Kievan Rus

Severely wounded in the battle, Harald, age fifteen, was helped to get away by Rognvald Brusason, a follower of king Olaf. Bruasson had been with Olaf for many years, brought together in a dispute about the Earldom of Orkney where Busason’s father Brusi, had sought Olaf’s support.

In fact, when Olaf had been banished from Norway in 1028, Brusason had followed him to Kievan Rus. To better understand the relationship with the Kievan Rus Empire, it was basically the eastern part of the region one might say was under viking rule during the Viking Age. Wife of the Kievan Rus prince Yaroslav, princess Ingegerd, was sister to Olaf II’s wife Astrid. Both daughters of the Swedish king Olaf Skötkonung.

Brusason helped Harald into hiding with a farmer living deep in the forest between Norway and Sweden. After a month or so, he was healed and, no surprise, they made their way to Kievan Rus. This meant traveling through Sweden and crossing the Baltic sea by ship, then likely sailing or rowing on rivers into the Rus empire. At the court of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, and his wife, the distant relative of Harald, they were welcomed with open arms.

Following Harald were several hundred men who had also survived and escaped after the Battle of Stiklestad. Prince Yaroslav had small and large conflicts with neighboring groups and getting an influx of hundreds of trained warriors was a great help.

Life in Kievan Rus

The Kievan Rus Empire was in conflict with the Poles to the east, which led to a larger campaign in 1031. To the west there was a near constant threat from various tribes from the giant steppes. They were the same steppes that Genghis Khan would come riding across a century later. With all these skirmishes and conflicts, Harald and his men saw plenty of action.

Later becoming a king, Harald naturally had many skalds write about him. One such poem is the Drápa about Haraldr harðráði (The poem of Harald Hardrada) by Bolverkr Arnorsson.

The first stanza describes Harald taking part at the Battle of Stiklestad and his first years in Kievan Rus.

Generous one, you wiped the sword’s mouth

when you had finished the fight;

you filled the raven with raw flesh;

the wolf howled on the hill.

And, resolute ruler,

the following year you were east in Russia;

I never heard of a peace-diminisher

becoming more distinguished than you.

(English translation by Ellen Gade)

Harald and his men stayed in Kievan Rus, serving in Grand Prince Yaroslav’s army for two to three years. It was the start of more than a decade in which Harald and his men served others for pay. Giving them riches beyond belief and military experience which would later propel him into the throne of Norway.

In 1033 or 1034, Harald and his men, possibly counting as many as five hundred, left the Rus Empire and traveled to Constantinople. Capital city of the Eastern Roman, or the Byzantine Empire. Constantinople was at the time known as the richest city in the world.

Harald’s Time in Byzantium and the Varangian Guard

Before exploring the time Harald spent serving, and eventually leading the Varangian Guard, a few points are worth reflecting upon. When he arrived in Constantinople, he was leading a group of around five hundred battle hardened viking warriors. Since losing in the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, they had been in battles and conflicts for three or four years.

When this group arrived in Constantinople, with Harald leading them, he was eighteen or nineteen years old. With their reputation preceding them, they were welcomed into the Varangian guard by the Byzantine Emperor.

The years Harald spent in Constantinople were especially tumultuous, even by Roman, or Byzantine standards. The sources are not entirely sure just when he and his men arrived there. However, there are some mentions in the sources that point to it being during the later stage of Emperor Romanos III Argyros reign. It might have been just after the passing of Romanos though.

Palace Intrigues in the Byzantine Empire

During the first half of 1034, when Harald possibly reached the city, Romanos III Argyros was emperor of Byzantium. Romanos had been a happily married noble at the Byzantine court until 1028. Then the dying emperor Constantine VIII, forced him to divorce his wife, and marry Emperor Constantine VIII’s daughter Zoë. Having no sons, the dying Constantine obviously wanted a son-in-law and the choice fell on Romanos. Having divorced his wife, who promptly was sent to a monastery, Romanos and Zoë married. Romanos was then proclaimed caesar, and Constantine died three days later.

Romanos was sixty, when he married Zoë, who was fifty. They were both forced into the marriage, and it’s fair to say it was likely not a very happy one. Suffice to say, there were several attempts on the throne, and both Romanos and Zoë had lovers outside their marriage.

Zoë had a younger man named Michael as a lover, and it’s believed the two conspired to have Romanos killed. He died April 11th, 1034, which saw Zoë and Michael getting married the same day. Michael then was proclaimed Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian. In 1034, he was twenty three or twenty four, which might explain why he got along so well with Harald. Bonding with a young viking warrior and son of a king.

The drama at the palace of Constantinople continued through most of the time Harald was there, and for years later. Only ending, or taking on a new form, after the death of Zoë in 1050.

Haralds’ Campaigns and Battles in Byzantine Service

Harald came to Byzantium as a teenager in 1034, leading a large group of warriors, all with recent experience from a few years fighting for the Kievan Rus. However, by the time he left Byzantium in 1042 he was a grown man, incredibly wealthy and with great military experience.

Originally the Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine empire had in fact survived the fall of Rome hundreds of years before. When Harald and his men arrived, the Byzantine Empire was nearing the tail end of a two hundred year “golden age.” During that time it was ruled by what is known as the Macedonian dynasty, mainly generals of Greek heritage. They had successfully strengthened the empire, while combating opposition from enemies on several fronts.

The Byzantine Empire was sourrounded by enemies

To the south and west, the Byzantine Empire clashed with Turks and smaller groups across Asio Minor, in modern day Turkey, Syria, Iraq and the Arabian peninsula. To the north and east, they were challenged by the Bulgars and Pechenegs, both groups they would have likely met before in the service of the Kievan Rus.

Arriving at the time they did meant that Harald’s group would be involved in innumerable military campaigns and larger battles. On a smaller, but equally dangerous scale, they were also directly or indirectly pulled into Byzantine court power struggles.

Below I have created an overview of the major areas where Harald and his men were involved in campaigns and battles. However, in reality it was likely not as linear as this presentation. With all the conflicts surrounding the sprawling Byzantine Empire, they were likely sent on other assignments as well. Heimskringla is sadly lacking in dates and specific details, even the chronology there is likely simplified. Much of what Snorri had to use as sources were skaldic poems written long after the fact. They also tend to be rather sweeping and broad, not necessarily a good source for detailed examination of facts.

1033-37 Pirates, Turks and Skirmishes in Afria and Asia Minor

Being vikings, it was probably only natural that Harald and his men would be assigned to combat pirates in the eastern Mediterranean. From around the many Greek isles, down to the Arabian Peninsula piracy was thriving. Combating pirates on the sea, they would also make landfall and go after pirates and Turk groups that might support them ashore.

This went on for a few years, and saw them fighting pirates and Turks all across what is modern day Greece, Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Northern Africa. Belonging to the Christian faith, Harald and the Byzantine Empire saw their enemies to the south collectively as the Saracens. They were the muslims of various Islamic nations or groups found all along northern Africa all the way deep into Turkey and Iraq and between.

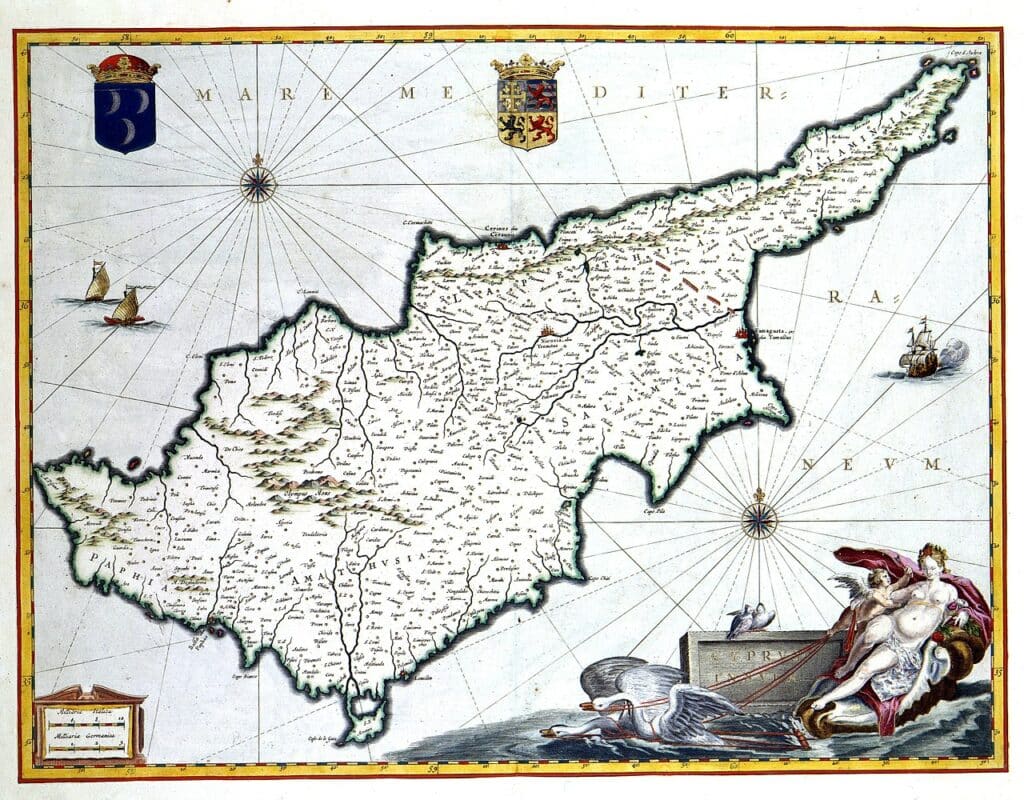

The island of Cyprus, basically right off the coast of modern day Turkey, then part of the Byzantine Empire was another possible hot-spot. The island had uniquely been shared by the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic Caliphate based in Egypt and Syria for several hundred years before recaptured by the Byzantines.

With all these campaigns also came great spoils. As was the custom of the time, the Varangians would share in the spoils of war. As their leader, Harald would over time build great wealth from this, which he kept sending back to Kievan Rus for safe keeping.

1036-1037 or around 1041 – Palestine and Jerusalem

According to the Heimskringla, Harald spent some time in Palestine and Jerusalem, possibly fighting off robbers and other unsavory elements attacking Christian pilgrims. However, this is said to have been after campaigns in Sicily and just before his return for Kievan Rus. This timeline has been questioned by several scholars which hold it as more likely this was some tim in the latter half of the 1030s. Less challenging than some of his other assignments, the Palestinian campaign is described like this in Heimskringla.

From Heimskringla, Saga of Harald Hardrada, Ch. 10

Harald went with his men to the land of Jerusalem and then up to the city of Jerusalem, and wheresoever he came in the land all the towns and strongholds were given up to him. So says the skald Stuf, who had heard the king himself relate these tidings:

To bring under the Greeks’ command;

And by the terror of his name

Under his power the country came,

Nor needed wasting fire and sword

To yield obediance to his word.”

Here it is told that this land came without fire and sword under Harald’s command. He then went out to Jordan and bathed therein, according to the custom of other pilgrims. Harald gave great gifts to our Lord’s grave, to the Holy Cross, and other holy relics in the land of Jerusalem. He also cleared the whole road all the way out to Jordan, by killing the robbers and other disturbers of the peace. So says the skald Stuf: —

“The Agder king cleared far and wide

Jordan’s fair banks on either side;

And his great name was widely spread.

The wicked people of the land

Were punished here by his dread hand,

And they hereafter will not miss

Much worse from Jesus Christ than this.”

1038-1041 Sicily and Southern Italian revolt

The history of the battles for control of Sicily is long and the rule of the island changed many times throughout history. From around 200 BA, and to around 400 AD, it was under Roman rule. Then, what had become the Western Roman Empire fell, and for the next hundred years or so Sicily fell into turmoil.

After several wars and different groups controlling the island, the Byzantines reconquered the island in 535 AD. They then held the island and the southernmost duchy of modern day Italy called Calabria up to the beginning of the 10th century.

The rest of Italy was taken over by a north Germanic tribe called the Lombards. From around 572 AD the Lombard Kingdom encompassed most of modern day Italy, except for the very southern part controlled by the Byzantines.

In 774 AD, the Franks, ruled by Charlemagne conquered the Lombards and they became a part of the sprawling Frankish Empire. Then, that empire fractured and was split into smaller and smaller pieces. Finally, in 869 AD, northern Italy was again an autonomous Lombard kingdom, albeit smaller than the previous one.

The Emirate of Sicily

Helped by infighting among the Byzantine leaders on the island, muslim leaders in northern Africa became more and more involved. In the early 900s, after many years of battle, Sicily came under Islamic rule, becoming the Emirate of Sicily.

Exerting their influence in the neighboring regions, the Emirate of Sicily would demand tribute paid by several duchy’s on mainland Italy. With this backdrop, the Byzantine Empire likely always saw Sicily as part of their empire, and never really gave up on getting it back.

Rise of the Normans

At around the same time the muslims took Sicily, another group of invaders saw great success in western Frankia. Led by the legendary viking chieftain Rollo of Normandy, vikings from Denmark as well as Norway and Sweden raided the west coast of the Frankish empire.

They were so successful that rather than continuing to battle them, the Frankish emperor King Charles III of West Frankia instead made peace with them. In 911 AD after a viking siege of the West Frankia town Chartres, a peace deal was made. The result was that the vikings were given a large region to rule as a duchy, under the Frankish throne.

Thus, The Duchy of Normandy was established, and the group later known as the Normans came onto the stage. As the viking settlers and the Frankish locals intermarried, their shared culture gave rise to the Normans as a group. As the Frankish empire itself became fractured and plagued by infighting, the “viking” Duchy of Normandy grew stronger.

Normans and Vikings Fighting Together and on Opposing Sides

In 1038, the Byzantine Empire started a longer campaign against the Emirate of Sicily, launching prolonged attacks on towns across the island. Led by the Byzantine general George Maniakes, who was also the ruler of Byzantine mainland Italy.

Alongside Maniakes troops were Haralds Varangians (he seems to be the leader of the guard by then) and Norman mercenaries. Interestingly, this shows just how far the vikings had come in terms of influencing the great powers of Europe. To the west you had Normandy and the Normans, to the east were the Kievan Rus and all over the Mediterranean were the Varangians.

The Scilician campaign came to a close early in 1041 AD after the Byzantines had taken most of the island. However, general George Maniakes had made some powerful enemies close to the Byzantine emperor, and he was recalled and later imprisoned.

Possibly in this power vacuum, the general had also been the Catepan of the Italian-Byzantine region; there was a revolt against Byzantine rule in the catepanate. Harald and the Varangians were dispatched from Sicily to put down the uprising alongside the new Catepan Michael Dokeianos.

The revolting Lombards were supported by the same Norman mercenaries that had fought alongside the Byzantines on Sicily months before. The Byzantine forces, along with the Varangians were defeated in two decisive battles in March and May of 1041 AD. As a result, the Byzantine Empire actually lost control of southern Italy. The Normans would end up ruling it and Sicily almost until the 13th century.

In the Heimskringla there are several interesting stories of towns taken by the Varangian Guard, led by Harald. I’m including one below to show both the ingenuity and tactical skills of Harald Hardrada in battle.

Saga of Harald Hardrada Ch 6. Battle in Sicily

Now when Harald came to Sicily he plundered there also, and sat down with his army before a strong and populous castle. He surrounded the castle; but the walls were so thick there was no possibility of breaking into it, and the people of the castle had enough of provisions, and all that was necessary for defence. Then Harald hit upon an expedient. He made his bird-catchers catch the small birds which had their nests within the castle, but flew into the woods by day to get food for their young.

He had small splinters of tarred wood bound upon the backs of the birds, smeared these over with wax and sulphur, and set fire to them. As soon as the birds were let loose they all flew at once to the castle to their young, and to their nests, which they had under the house roofs that were covered with reeds or straw.

The fire from the birds seized upon the house roofs; and although each bird could only carry a small burden of fire, yet all at once there was a mighty flame, caused by so many birds carrying fire with them and spreading it widely among the house roofs.

Thus one house after the other was set on fire, until the castle itself was in flames. Then the people came out of the castle and begged for mercy; the same men who for many days had set at defiance the Greek army and its leader. Harald granted life and safety to all who asked quarter, and made himself master of the place.

1041-1042 Final Battles and Byzantine Prison

After the revolt in southern Italy, Harald and the Varangians seem to have come unscathed out of any political intrigue. The Catepan Michael Dokeianos however was recalled to Constantinople to likely answer for having lost Italy and Sicily. The Varangians on the other hand were sent to yet another battle. This was late in 1041 AD and saw them battle with the Bulgars, in an uprising in the Bulgarian region.

Things at the Byzantine court took a turn on 10th December 1041 AD when Emperor Michael IV died. Having had no sons of their own, Michael IV and empress Zoë (the one really pulling the strings all along) had adopted Michaels nephew. Three days after his adoptive fathers death, Zoë proclaimed Michael V as the new Emperor of Byzantium. However, Michael V had a will of his own and did not want to be co-ruler alongside his adoptive mother Zoë. In April of 1042 AD, Michael V banished Zoë to a monastery after she reportedly had plotted to poison him. This led to a popular uprising of the people in Constantinople who seems to have held Zoë and her sister Theodora in high regard.

Harald in Prison

In the midst of this turmoil were the Varangians, apparently on both sides. Some siding with the de-facto emperor Michael V, and some, like Hardrada, on the side of the banished empress Zoë. Admittedly, the details are sparse, but Harald was possibly thrown in prison for a while during this period.

The uprising against Michael V led to him fleeing for his life and Theodora being named empress alongside her sister Zoë. Then promptly, the Varangian guard was sent to find him at a monastery where he had taken refuge. He was then blinded, possibly by Harald Hardrada himself, and banished to a monastery outside of the city.

1042 Harald Hardrada Escapes Constantinople

The Heimskringla is a little unclear about the events that led to Harald being imprisoned, and just which party he supported in the internal power struggle at the court. It seems apparent that Snorri Sturluson took some liberties, and possibly could not find many details when he was writing this down two hundred years after the fact.

However, there are other sources from the Byzantium side which are a lot more detailed. The empire had historians throughout the ages, and the Orthodox church which was very involved also kept records of more official events.

The two co-ruling sister Empresses Zoë and Theodora did not get along and to curtail the sisters’ powers, Zoë sought to marry. Her husband would become an emperor, making Theodora a third wheel of the “emperor wagon”. After some back and forth, where Zoë according to the Heimskringla wanted to marry Harald Hardrada among others, she finally married Constantine Monomachos, who became emperor. Just for fun, or maybe out of love, the good Constantine brought along his mistress into the court.

Amidst all this, Harald Hardrada decided he had outworne his welcome at the Byzantine court and decided to leave. Possibly coinciding with Zoë looking for a husband, his “resignation” from the Varangian Guard was refused. However Harald was determined to leave, with quite a few varangians wanting to follow him. The Heimskringla relates a great story of their escape in a boat, despite the iron chain shutting off the harbor. In this story there is mention of a woman named Maria, but she seems to be an invention of Snorri’s.

Heimskringla, Saga of Harald Hardrada Ch 15.

The same night King Harald and his men went to the house where Maria slept and carried her away by force. Then they went down to where the galleys of the Varings lay, took two of them and rowed out into Sjavid sound.

When they came to the place where the iron chain is drawn across the sound, Harald told his men to stretch out at their oars in both galleys; but the men who were not rowing to run all to the stern of the galley, each with his luggage in his hand.

The galleys thus ran up and lay on the iron chain. As soon as they stood fast on it, and would advance no farther, Harald ordered all the men to run forward into the bow. Then the galley, in which Harald was, balanced forwards and swung down over the chain; but the other, which remained fast athwart the chain, split in two, by which many men were lost; but some were taken up out of the sound.

Thus Harald escaped out of Constantinople and sailed thence into the Black Sea; but before he left the land he put the lady ashore and sent her back with a good escort to Constantinople and bade her tell her relation, the Empress Zoe, how little power she had over Harald, and how little the empress could have hindered him from taking the lady.

Poem by Hardrada

Harald then sailed northwards in the Ellipalta and then all round the Eastern empire. On this voyage Harald composed sixteen songs for amusement and all ending with the same words. This is one of them: —

“Past Sicily’s wide plains we flew,

A dauntless, never-wearied crew;

Our viking steed rushed through the sea,

As viking-like fast, fast sailed we.

Never, I think, along this shore

Did Norsemen ever sail before;

Yet to the Russian queen, I fear,

My gold-adorned, I am not dear.”

With this he meant Ellisif, daughter of King Jarisleif in Novgorod.

Harald Hardrada Returns to Kievan Rus

Having successfully left Constantinople behind, Harald Hardrada and his men traveled across the Black Sea. Then up the river Dnepr, into Eastern Europe to get to Kyiv, at the heart of the Kyivan Rus Empire. Interestingly, a short time later, in 1043, the Kyivan Rus launched a naval attack on Constantinople, but it didn’t succeed.

While in Kyiv, Harald finally married Elisiv, daughter of prince Yaroslav the Wise. He had clearly fallen for her the first time he went through Kyiv. The love sick younger Harald actually wrote several poems mentioning her while in the Varangian Guard. Her sisters were married to a Frankish king and a Hungarian king. With that history, it was not a given that Harald would measure up. However, the riches he had amassed were like nothing anyone had seen before. Moreover, he was heading back to Norway to make a bid for the throne.

Part of his great fortune was, according to Heimskringla, because he three times had been part of the “poluta-svarf”, or palace plunder. According to myth, and some more or less reliable historical sources, the Varangians were allowed to “plunder” the coffers when a Byzantine emperor died. Likely ensuring their loyalty to the new emperor as well.

After around three years in Kievan Rus, in 1045 or early ‘46, Harald and his men moved through the Rus empire, towards Norway. Traveling on rivers, they eventually reached the bay of Finland and then crossed the Baltic sea to reach Sweden.

Harald Makes a Play for the Norwegian Throne

In Sweden, Harald Hardrada sought support from king Anund Jacob in his bid for the Norwegian throne. In this regard, I am sure his immense wealth played a not insignificant part. While still in Sweden Harald also joined forces with the ousted Danish regent-in-waiting Sweyn Estridsson.

Sweyn and the Danish Throne

In 1042 the Danish king, Harthacnut, son of the Danish king Cnut whose forces had beaten king Olaf at Stiklestad died. Based on a previous peace agreement between Harthacnut and king Magnus the Good, whoever survived the other would become king of that land as well.

This agreement didn’t sit well with Harthacnut’s cousin Sweyn Estridsson who he had left as ruler of Denmark in his place as Harthacnut had been in England. Even though Sweyn did have some local support, king Magnus was able to quickly put down any challenge to his claim. So Magnus was successful in becoming king of both Norway and Denmark, at the age of eighteen. Sweyn Estridsson however, at the age of twenty three, took refuge in the east. This was definitely a time when kids grew up fast.

Sweyn, Anund and Harald Join Forces Against Magnus

With the goal of first taking the Danish throne away from Magnus, the combined forces started a series of attacks along the coast of Denmark. The idea was possibly to instill upon the people there that Magnus could do nothing for them and that Sweyn would be better for them.

Wise beyond his years, or possibly supported by great advisors, Magnus the Good sought to reach an agreement with Harald rather than fight him. Not long after their campaign of attacks on Denmark started, Harald and Magnus decided in 1046 on a deal to be co-regents of Norway. A deal which basically left Sweyn out in the cold. Surprisingly, this arrangement only lasted a year or so, as Magnus died suddenly in 1047.

When Magnus the Good died, Harald Harada became the sole king of Norway. However, on his deathbed king Magnus had decided the Danish throne should go to Sweyn Estridsson, rather than to Harald.

To me this puts into great perspective the willingness to compromise and work out strategic alliances at the time. Sweyn’s uncle Cnut had opposed Magnus’ father Olaf, a conflict in which Olaf was killed. Then Sweyn and Harald had forced Magnus into a co-ruling arrangement with Harald. Yet, despite this history of violence between these men, he granted Sweyns’ wish to become king, maybe seeing that he had a stronger connection to the land through his uncle.

Harald Hardrada King of Norway – and Denmark?

In 1047 AD then, Harald Hardrada was the king of Norway, and he had a clear eye on the Danish throne as well. Not exactly pleased with how Magnus had given it away, he started on a years-long campaign against Sweyn and the Danes.

However, an interesting point is that while Harald was the king of Norway, his rule wasn’t absolute. There was strong opposition to him among some of the chieftains in Norway, notably among the clans belonging to the western, and northern part of the country. Harald and Olaf and their families on the other hand were based more in the south-east and middle of Norway.

This opposition were the same local chieftains who had supported king Cnut against Olaf Haraldsson at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030. The same chieftains actually cut Haralds plans short when he proclaimed in 1047 that he wanted to raise an army and attack Denmark. Led by the local noble Einar Thambarskelfir, they curtailed Harald and his ability to gather an army large enough to really threaten Sweyn.

Instead, Harald, using his more loyal followers, engaged in a protracted campaign of frequent attacks on Denmark. It’s only about 120 nautical miles from the south of Norway to the north of Denmark. A distance that could be less than a day’s sail. Close enough that the Norwegians could harass both the eastern and western Danish coasts and leave before Sweyn could react.

1048-1064 Campaign of Attacks on Denmark

Not one to give up easily, Harald kept up with attacking Denmark pretty much every year, from 1048 until 1064. There were few large battles, and many more raids and sackings of large and small towns along the Danish coast.

The most notable of such sackings was a raid on the Danish town of Hedeby in 1049 AD. It lies deep in the south of Denmark. At the time it was the largest city in Denmark, and a bustling trading center. Situated inland, but connected to the Baltic sea by a long, and easily navigable inlet it was both well protected, and ideally located for trade.

Maybe even more impressive, and speaking to the importance of the city, it was protected by the Danevirke fortifications. The Danevirke is a set of wood and earthwork walls and fortifications which protected the Danes from the Frankish Empire to the south. It was started upon already in around 650 AD and by the time of Harald and Sweyns feud, it was a system of around twenty miles of fortifications.

Stretching out from that long inlet, west across the bottom of the Danish peninsula, it was so successful it was in use all the way up to the 19th century. There were also separate fortifications surrounding most of the city proper, opening up only towards the sea.

Despite its fortification however, knowing the wealth of the town, and its importance to trade for the Danes, Harald attacked it in 1050. Successful in attacking it from the sea, Harald Hardrada and his men burned the city to the ground after having plundered it.

Harald Gives up on Denmark

In 1064 AD (or 1065 depending on the source), after sixteen-seventeen years of a more or less relentless campaign against Sweyn and the Danes, Harald decided to end hostilities. With all the battles and losses, the campaign had been a huge strain on the economy on both sides.

Coming to a cease of hostilities, both parties agreed to keep the old borders as they had been and not demand compensation from either side. While likely a great decision for the warriors, and farmers who were regularly called out to battle from both sides, it might not have been the best for Harald Hardrada.

Viking Age chiefs and kings came with all kinds of ambitions and different ways of ruling. Harald Hardrada was definitely in the camp who did not shy away from conflict, and was driven by an ambition of conquering people and lands. However, during his reign of Norway, Harald actually accomplished much more than just wage war.

Norway Under Harald Hardrada

With Harald Hardrada the focus of his story is often the Battle of Stamford Bridge, or his time in the Varangian Guard. However, by all accounts he was also a good, or effective might be a better term, ruler of Norway from 1047 AD to his death in 1066 AD.

Taking the throne as he did, and being rather unyielding in his convictions, he faced strong opposition in the early years. That was, until he made the former petty kings yield to his will, or die by his sword. It was in this period he got the epithet Hardrada, meaning hard, maybe even tyrannical ruler.

Under his reign, Harald would brutally stomp out rebellion against his rule. Importantly, taxing wealthy farmers and villages was a great source of income for the crown, and king. Especially in the early years there were some instances where people paid their tax to opposing chieftains, rather than Harald. In response, Harald and his men would raze whole villages, burn down farms and confiscate property. In the end they all, more or less willingly accepted him as king.

Earls of Lade and Einar Thambarskelfir – The Main Opposition

Early in the Viking Age Norway was divided into several smaller kingdoms, ruled by a petty king, or Jarl. At times, the whole nation was ruled by the Danish king, with a local governor representing him. One center of power among these Jarls was around Lade, close to Nidaros and the modern day city of Trondheim. The Earls of Lade had a long and proud history going back several hundred years. At times, the clan was governing Norway on behalf of a Danish king.

It was here that the main opposition to Olaf II and later Harald Hardrada was found. They were representing the Danish king as he ruled Norway from 1000 to around 1015. Then again from 1028 after Olaf II was chased out of Norway. In 1035 the Danish king Cnut the Great died, leaving the Norwegian throne his son Svein Knutsson had held in limbo.

Tired of being ruled by the Danes, the Earls of Lade, with Einar Thambarskelfir leading them devised a rather ingenious plan. Rather than trying to take the thorne himself, in 1035 Einar and some others brough Olaf II’s son Magnus back from Kievan Rus and proclaimed him king. Magnus, later known as king Magnus the Good, was all of eleven at the time. Only a boy, his rule was made possible by the support of the Earls of Lade, and chief among them, Thambarskelfir. In reality this made him the de facto ruler, controlling the boy-king Magnus.

With a firm grasp of the throne, albeit indirectly, Thambarskelfir had advised Magnus against the co-rule of Norway with Harald which came about in 1046. Having most likely hoped for his own son to take the throne at some point. Magnus died shortly after and Harald became sole king instead in 1047.

Rooting Out the Opposition

Thambarskelfir was thirty five years older than Harald and not afraid to speak his mind. Even though Harald was the recognized king, Thambarskelfir would speak up at the thing, about anything he was unhappy with. If that meant going directly against Harald and his interests, that seems only to have motivated him more.

At one point, when Harald was in Trondheim, Thambarskelfir came into town with seven or eight ships and as many as five hundred warriors. Not one to scare easily, king Harald wrote a poem about this found in the Heimskringla. Poem found in Ch. 43, my own translation:

I see the mighty Thambarskelfir stride,

With pomp and pride, his power wide,

Across the shore, up to the land,

Surrounded by his armed band.

This leader thinks he’ll rule the land,

And take the royal throne in hand.

I’ve known an earl with fewer men,

Leading better than this one can.

He, who strikes sparks from the shield,

Einar, might one day make us yield,

Unless our axe’s sharp edge ends,

With a swift kiss, what he intends.

It should surprise no one that Harald followed through on his beliefs. In 1050, at what was purportedly a meeting for a negotiation between Einar Tambarskelfir and the king, Harald Hardrada had both Einar and his son Eindride killed. Einar’s widowed wife tried to launch an attack on king Harald at his home in Nidaros, but he had already left.

Furthering Christianity and Establishing a Norwegian Currency

Harald Hardrada might have been a ruthless ruler. However, he also championed several causes and policies that were largely good for Norway, or at least not as controversial. For one, he established a coin based monetary system. Being a very well traveled man, he had seen how coins were used in other parts of Europe, even Denmark.

On one side, likely the front, there is a Triquetra, a symbol used both by the Norse and Christians. Around it is the inscription HARALD REX NO, for “Harald King Norway”. On the other side, there is a cross, and the inscription VLF ON NIDARNE, meaning Ulf at/on Nidarnes. So that coin was made at the royal mint in Nidaros, and the responsible, coin master, was named Ulf.

In Harald’s time, Christianity was also promoted across Norway. He funded the building of churches and invited priests from Kievan Rus and the Byzantine Empire to spread the gospel. However, and I feel this is an important point, this Christianization of Norway is often misunderstood. It did not mean that they fully abandoned the old pagan beliefs of their Norse ancestors.

The idea of having only one god must have only gained adaptation much later. You find evidence of this in jewelry of the time, using both Norse and Christian symbols together. Even the skalds, composing poems about the Christian king Harald, would also refer to gods or beings from Norse mythology. Certainly, Christianity was a political weapon, as much as a belief system during the late stages of the Viking Age. The transition into Christianity across Scandinavia lasted for a long time after.

Haralds Exploration of his Norwegian Kingdom

Ever the adventurous and curious spirit, Harald traveled all across Norway. Visiting more remote regions in the central parts, well into what is today Sweden. Moreover, he also sailed extensively along the coast. In a passage from the book Gesta Hammaburgensis, written by Adam of Bremen around 1073-1076 , this is retold.

“The most enterprising Prince Haraldr of the Norwegians lately attempted this [sea]. Who, having searched thoroughly the length of the northern ocean in ships, finally had before his eyes the dark failing boundaries of the savage world, and, by retracing his steps, with difficulty barely escaped the deep abyss in safety.”

Reflecting the belief of the time that if you sailed far enough, you would indeed find the end of the world, and risk falling off.

To me this is sort of strange as Harald surely must have known about both Iceland, and even how Erik the Red had discovered Greenland some sixty to seventy years earlier. Leif Erikson, who discovered North America, was also a Christian and had been charged with spreading Christianity on Greenland in around 1000 AD. Being king of Norway for so many years, it is sort of curious he never felt the pull to visit this “new land”.

Instead, like the legendary viking king Ragnar Lothbrok two centuries before, Harald had his eye on something much closer to home, the English throne. Since the late 800s when the Great Heathen Army, led by Ivar the Boneless managed to conquer a large part of Britain, both Norwegian and Danish Vikings often plotted to take Britian.

Multiple Claimants to the English Throne

In January 1066 AD, then king of England, Edward the Confessor died, widowing his wife queen Edith and leaving no children. This set in motion the events leading to the death of Harald Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, which in turn helped facilitate the more successful invasion of England by William the Conqueror, the first Norman king of England.

This was much the same that had happened when Harald himself took the throne of Norway, and later tried to take the throne of Denmark. The death of a sitting king, and multiple competing claims to the throne led to war. In a situation of turmoil and war, others with less legitimate claims, but strong ambitions, might also see an opportunity.

The Godwinson Brothers and Their Sister Queen Edith

Harold and Tostig Godwinson were sons of the powerful earl Godwin of Wessex, and Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, a Danish noblewoman. They had several other brothers and sisters, but their sister Edith is the important one in this story. Edith was the queen, through her marriage to king Edward, the brother-in-law to Harold and Tostig.

Through their mother, they were nephews of Ulf the Earl, who was married to Estrid Svendsdatter. Their aunt Estrid in turn, was the daughter of the powerful Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard, and half-sister to King Cnut the Great. Ulf and Estrid’s son Sweyn Estridsson Ulfsson, first cousin of Harold and Tostig, would later become king Sweyn II of Denmark.

The very same king Sweyn Harald Hardrada had waged war against for nearly twenty years for the throne of Denmark.

Harald’s Claim to the English Throne

While not having a claim to the throne through blood, Harald had inherited a claim from his nephew and co-regent Magnus the Good. Magnus had been put in the Norwegian throne after Cnut the Great, king of Norway, Denmark and England died. Cnut’s son Harthacnut didn’t have the forces necessary to keep his fathers North Sea Empire together and relinquished the Norwegian throne to Magnus, but kept the Danish throne and held on to England using his half-brother as regent in his place.

After a longer conflict, Magnus and Harthacnut agreed to stop hostilities. Then then agreed that either one who survived the other, would inherit his claim and kingdoms. However, when Harthacnut died, Magnus successfully took the Danish throne, but lost England to Harthacnut’s half-brother Edward the Confessor.

Not one to let a slight go unnoticed, or a claim to a throne lay dormant, Harald saw a path to the English throne when Edward died.

The Competing Godwinson Brothers

Before the death of Edward, Harold had been a close advisor of his. Tostig was more out on the periphery, both geographically and apparently in the matter of trust between them. Tostig, while from the south, had been made Earl of Northumbria, north in the country. After a rebellion against Tostig’s harsh rule, Edward, advised by Harold, exiled Tostig from England in the fall of 1065.

Upon his deathbed, king Edward named his brother-in-law Harold his successor, early in the new year of 1066. Tostig however, was formenting his plan of revenge he wished on his brother. Blaming him for what he saw as his part in his exile. Plotting just across the English channel, a guest of his brother-in-law the Count of Flanders, who incidentally was the father-in-law to William the Conqueror.

William had already openly stated that he intended to take England, and the throne by force. Getting a visit by Tostig, William was likely interested in hearing anything Tostig would share. However, in the end he did not support him against Harold.

However, whatever William said to Tostig, it certainly didn’t dissuade Tostig from challenging Harold. In the spring and early summer of 1066, he launched into a series of smaller attacks along the English coast. While Tostig and his supporters had little success, the whole point might have been to just stir things up. As Tostig would later join forces with Harald and attack from the north, what better than if king Harold believed things were erupting in the south and east. By the mid summer of 1066 Tostig had sought refuge with his friend the king of Scotland, having worked himself up north along the coast.

Harald Hardrada and the Invasion of England

The power struggle, and basically brewing war for the throne of England was Haralds opportunity to make his play for the throne. However, this wasn’t his first outing when it came to his ambitions for England.

Already in 1058 he had sent a fleet into English waters, nominally led by his ten year old son Magnus. They were involved in some smaller conflicts in Wales, Ireland and the Isles, covering all the islands from Isle of Man to the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland. This region, right off the coast of England and Scotland was historically a stronghold of the Norse. It was where they started their raids late in the 700s.

Exerting his influence, positioned Harald as a power in the region and the Norwegian presence was certainly felt. After the death of Edward the Confessor, Harald was seemingly quick to start planning an all out attack on England.

As soon as the ice cleared after the winter of 1066, his ships, and those of his loyal chieftains were gathering in the Sognefjord. Obviously in contact with his people in England, and with Tostig, they planned a large-scale invasion.

In September of 1066 AD, around 250 viking longships and nearly ten thousand men sailed across the North Sea. Seemingly planning for what would come after his victory, he also brought his wife queen Elisiv, their daughters and his son Olav by his other wife Thora. Before leaving Norway, he proclaimed his son Magnus to be king in his place, and left Thora with him.

Making Landfall in England

En route to meet with Tostig on the English mainland, the fleet made stops first on Shetland and the Orkneys. There they both picked up more men, and Harald left his wife and children in the Orkneys.

Next they made a stop in the then capital city of Scotland. There they picked up around two thousand more soldiers from the Scottish king. King Malcolm III of Scotland was a friend and ally of Tostig so supported him. Even if it meant giving the English throne to Harald.

On, or around September 8th, Harald met up with Tostig and his considerably smaller fleet at Tynemouth. Lying on the river Tyne, it allowed for the fleet to anchor in the large mouth of the river, while contemplating their next move. Not surprisingly, their plan turned out to be raiding cities and towns along the North East coast.

On September 20th they sailed, or rowed up the wide river Humber, making landfall at the town of Riccall. The small town is only about ten miles south of the great city of York. The Norsemen had renamed it Jorvik when they first took it back in the 800s. Being at the heart of Northumbria, York would be a strategic and symbolic city to capture.

Obviously well aware of the advancing vikings, the local forces from Northumbria and from Mercia (the two Earls were brothers) met Haralds advancing forces the same day. This has become known as the Battle of Fulford, fought just two miles south of the city of York.

Harald and Tostig won the battle, and York surrendered to them soon after, on or before September 24th. Having taken some losses, they likely raided and restocked from whatever they found in York.

Their Situation After the Battle of Fulford

On the morning of September 25th, Harald, Tostig and some of their men were supposed to meet leaders from York. Ostensibly to agree on who would manage the city under Harald. The meeting would take place by the Stamford bridge which crosses the river Derwent, about five miles east of York.

Before diving into how this day went badly wrong for them, I feel it’s worth shortly recapping their situation. Haralds fleet had met with Tostig and started their campaign on September 8th, just two weeks earlier. Having fought and sacked several smaller towns, they fought a major battle on the 20th and took York. After the battle, and looting York, they went back to their camp by their boats in Riccall.

Historical records state that they suffered heavy losses in the beginning of battle. One might assume that more than a thousand men might have been killed. Many more would be wounded and more or less taken out of the fight to come for a while.

They had also raided several towns, and taken the rich city of York. By now, most likely their ships were holding some of the loot. Furthermore, being important in their own right, some men would be left to protect them. This all added up. On that on that fateful day, Harald and Tostig only brought about two thirds of their men to meet the people from York. Not expecting a major battle, they wore no heavy armor, and possibly also did not bring all their weapons.

Unbeknownst to them, king Harold Godwinson and his army were marching as fast as they could up from the south-west. Meeting no resistance in York on the morning of the 25th, they marched right through it. A little over an hour later, they arrived at Stamford.

The Battle of Stamford Bridge

The bridge was the only thing between the advancing army of king Harold, and the outnumbered and ill-prepared forces of Tostig and Harald Hardrada. Legend has it, and several sources mention this, that a large berserker viking warrior armed with a broadax was able to hold back their advance. Holding the bridge long enough for Harald to organize their forces as best they could.

However, they were vastly outnumbered and missed their armor and some of their weaponry. King Harold and his army beat the forces of Harald and Tostig. Harald Hardrada was struck by an arrow to the throat and died early on in the battle of Stamford Bridge. Quite unlike the two earls they beat at the Battle of Fulford, Harald led from the front.

In researching this post I read the different sagas and a whole book on Harald Hardrada. I have a feeling he was a man more content at war, than in a time of peace. His adult life spans more than thirty years from the Battle of Stiklestad, through fighting in the Kievan Rus, and in the Varangian guard. Finally launching into the campaign against Sweyn for the throne of Denmark. Harald Hardrada spent most of his life at war.

Christian or not, I am sure the valkyries brought him to Valhalla when his life ended on the battlefield. There, the greatest viking warrior to have lived gets to feast and battle into eternity.