The Varangians were, initially, primarily Swedish Rus (Vikings from Sweden). They had sailed and rowed their ships down the long rivers of Russia and Ukraine to the Black Sea. There they made contact with “Miklagard,” – Constantinople. “Miklagard” means “Great City” in Old Norse. At the time, Constantinople was the greatest city in Europe. It surpassed even the size and riches of Paris.

Who were the Varangians?

Members of the Varangian Guard called themselves “Væringi,” meaning “sworn companion.” The word was Hellenized (made Greek) as “Varangoi.” To Northmen and Byzantines, the word came to mean “foreigner who had taken an oath to a new lord.” In this case, the lord was the Byzantine or Eastern Roman emperor.

Notice that the word refers to “foreigners,” not just Swedish Rus. The Byzantine emperors were in awe of the Northmen’s size, skill, and ferocity, but other Northern Europeans also became “Varangoi.” These included large numbers of Norwegians, Anglo-Saxons and Franks. These men made their way eastward for both adventure and pay in the service of the wealthiest empire in Europe at the time. However, until the 11th century, the majority of Varangians were Scandinavians. At least one of those Scandinavians was an Icelander, Bolli Bollasson. Bolli is recorded in the “Laxdɶla Saga” as having come home from the east dressed as a typical medieval knight.

How did the Varangian Guard begin?

Some Swedish Rus entered service in Constantinople in the early 870s. Byzantine Emperor Basil II formed the Varangian Guard in 988. Basil II is known as “The Bulgar Slayer” for his defeat and treatment of captured Bulgarians.

In 1014, Basil’s army, which included some Varangians, inflicted a heavy defeat on the Bulgarians at the Battle of Kleidion. Legend says that 99 out of 100 of the 15,000 Bulgarians taken prisoner were blinded. Varangians likely did some of that eye-gouging.

In 989, Rus leader Vladimir sent 6,000 Rus warriors to Basil II. The sending of these men to Constantinople had three primary purposes. One was to improve relations between the Rus and Byzantines. Two, as “bride-price” for the hand of Basil’s sister in marriage. Three, to rid Vladimir of his most unruly soldiers – many of which he could not afford to pay at the time.

How big was the Guard?

6,000 is also the number given from the early 1100s. These 6,000 were reportedly Norwegians under King Sigurd Magnusson, who, unfortunately for him, returned to Norway with only one hundred men.

During the 4th Crusade in the summer of 1023, Crusaders wanted to loot Christian Constantinople and lay siege to it. It is reported that 6,000 Varangians manned the walls of the city.

Given that the Varangians served as more than just bodyguards, the number of guardsmen was more than 6,000, but probably not much more. More Varangians meant a higher likelihood of them becoming too powerful within an empire full of intrigue.

What do you pay a Viking?

If the original 6,000 sent by Vladimir to Basil were underpaid, you can bet Basil likely paid them well. Not only was he rich, but he was also smart. 6,000 destitute Vikings in the richest city in Europe is not a good idea. How were the Varangians paid?

We know that the Vikings were paid, but we do not know how much. It seems likely that they were paid a handsome and regular amount. Though the Northmen prided themselves on being loyal to their oaths, neither Basil or his successors were dumb enough to be cheap with the Vikings.

We do know that the Varangians were given a share of the spoils of war. This “payment” could come in the form of gold, silver, jewels, wine and women. We know from contemporary accounts that the Varangians prided themselves on their appearance, and were said to wear jewels in the ears and around their necks.

Benefits

The Guard also received less tangible benefits. They likely did not have to pay taxes. They received the benefit of the doubt when testifying in court. Guardsmen could carry their weapons publicly when off-duty – Byzantine citizens were not permitted to carry weapons.

Since they were often responsible for the safety of the emperor of his family, they had access to the palace and its amenities. Lastly, they enjoyed a special and elevated status within the empire, and especially Constantinople, which likely provided them “other” benefits.

Religion

In 988, Vladimir converted to Orthodox Christianity, and it’s likely that some of the 6,000 he sent to Byzantium were already Christian. It also seems likely that those who weren’t Christian converted, at least outwardly, when they arrived in Constantinople.

Increased trust, access to important areas, and more pay was probably good enough reason for conversion. We can make a safe assumption that some pagan culture remained within the ranks of the Varangians in the form of language and attitude towards the afterlife.

Famous Varangians

The most well-known Varangian wasn’t Swedish, surprisingly. He was the Norwegian warrior, and later, king, Harald Hardrada (“hard-ruler”). Though we don’t know whether Harald actually did it, but history credits him with the now-famous trick that the TV version of the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok carried off in Paris – faking his own death and “arising” his coffin within the city walls of his enemy. In TV Ragnar’s case, it was Paris. In history books, it was Harald, and the town was in the Balkans – where enemies of the Byzantine Empire were growing stronger.

We also have the names of a few other well-known Vikings who were at one time or another, in the pay of the Byzantine Empire. Rurik, the prince that legend has founded the Rus’ dynasty was one. Another was Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye (a son of Ragnar on TV), and who may or may not have existed, and “Ulf the Quarrelsome,” a Jarl who is mentioned in Icelandic sagas and who was renowned for his strength and ferocity in battle.

Based on the descriptions of many of the Varangian Vikings its fair to assume that several of them were so-called berserkers. Hailing from the more elite, or crazy, among the Viking warriors.

Harald later went on to become King of Norway, and had a remote claim to the English throne. In 1066, he invaded Northern England with the last great Viking army. He was defeated at Stamford Bridge by Harold Godwinson, who soon after went to meet his defeat at the hands of William the Conqueror.

Varangian Runes

We have written evidence of Northmen in Constantinople, left by the Varangians themselves, in the form of runic inscriptions. The most unusual and well-known of these aren’t on a rune stone. Instead it’s in the famous “Hagia Sofia” in Istanbul, as modern Constantinople is called.

Inside the former church (now a mosque) is runic graffiti. Scratched into the stone are two Viking versions of “Kilgore was here,” the famous graffiti of Allied soldiers in WWII: one has most of the runes for the name “Halfdan,” and the other one is signed “Arni,” both of which are only Norse names.

Along with the “signatures” of Arni and Halfdan, many runestones, all of them in Sweden, mention Swedish Vikings in “the east,” as the Byzantine and Rus empires were known. Most runestones are memorials of men who “died in the East.”

Varangian Battles

The Varangians also served as a kind of police force in Constantinople, though it was as imperial bodyguards and soldiers that they gained their fame. From the time they were formed before 1000 AD until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, men calling themselves members of the Varangian Guard helped defend the city and the empire from enemies on all sides.

We’ve already mentioned the eye-gouging Battle of Kleidion in 1014. In 1071, men of the Guard and the Byzantine armies faced the invading Seljuk Turks. The Seljuks defeated the Varangians at the Battle of Manzikert, establishing a permanent foothold in Asia Minor for Turkic people. At the Battle of Beroia in 1122, the Varangians helped defeat another Seljuk army. Finally, in 1203-04, the Varangians played a crucial role in defending Constantinople. Though the emperor and the Guard had to flee, the city was retaken in 1271, and a later generation of Varangians took part in the conquest.

The Varangians fought hundreds, perhaps thousands, of more minor battles throughout their history.

What happened to the Varangian Guard?

The Ottoman Turks finally took Constantinople in 1453 after years of siege and decades of trying. Though there were men in the city calling themselves “Varangians” at the time, by the 15th century, “the Guard” consisted primarily of non-Scandinavians and played a largely ceremonial role.

Between 1203 and the Byzantine return to the city in 1271, many of the Viking/Varangian guardsmen likely dispersed and never returned. The Byzantines retained control of large parts of their empire, but islands, mountains, and dangerous enemies often separated those parts. After the Crusaders sacked Constantinople, written descriptions of the Varangians almost wholly cease.

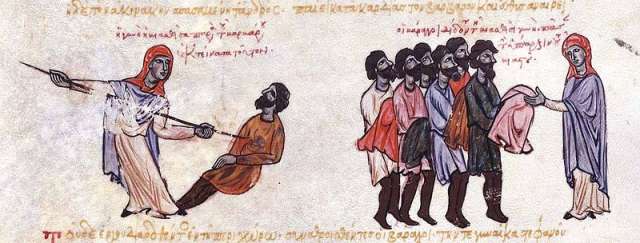

Featured Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons