I have always found it strange that so many consider the raid on the monastery on the island of Lindisfarne in AD 793 to be the start of the Viking Age. It makes it sound like the people we now call vikings came out of nowhere and suddenly attacked a christian monastery in England.

The Norsemen, people from across what is now Denmark, Norway and Sweden, shared a common culture, language and ethnicity. A lot of archeological finds from the 6th and 7th century attest to this shared culture. It seems fair to say that the viking culture as we know it, had been around for well over a hundred years before the “Viking Age”.

The Norsemen Start Exploring and Raiding

For some reason however, the Norsemen became more mobile, and ventured further and further outside Scandinavia. The exact reason why they started on their almost three hundred years of exploration and settlement isn’t entirely known. There are some theories though. One such theory is that lack of land meant more and more men grew up not inheriting a farm. Instead of just working as farmers on someone else’s land, they were eager to make a living in some other way.

The culture in Scandinavia, in what was to be known as the Viking Age, was a decidedly violent one. The concept of honor, and the right of the strongest were strongly held. Yet their society was governed by rules and even laws. However, if someone desired someone else’s land or even wife, he could challenge the other. Upon killing him, which would often be the case if a berserker warrior challenged a farmer, he could, take what he wanted.

The Danish and Norwegian vikings took to raiding British monasteries and towns in the 790’s. Later viking invasions and settlements would shape England into what it still is today. The first violent attack recorded by the Saxon Chronicle was on a reeve named Beaduheard. However, another raid would become much more infamous, and known as the start of the VIking Age. This is the raid on “Holy island”, and the monastery on Lindisfarne in AD 793.

The Lindisfarne Monastery and Bishopric

Established in the first half of the 7th century, the monastery and bishopric on the island of Lindisfarne was the center of christianity in the kingdom of Northumbria. The bishop at Lindisfarne would grow to have vast influence even reaching outside of Northumbria. The 8th century historian Bede wrote that he at one point held influence over all of southern England.

The rise and prominence of the monastery clearly grew from its strong support by the Northumbrian king Oswald. When Oswald was around twelve, in ca. AD 616, his father was killed by Oswald’s uncle Edwin, who then expelled Oswald and his brother. Finding refuge on the island of Iona, on the west coast of modern day Scotland, young Oswald and his brother were converted to christianity.

Years later, in AD 634 Oswald retook Northumberland, becoming king like his father and uncle before him. He then invited the monk Aidan (later St. Aidan) and a group of Irish monks from the island of Iona to establish the monastery on Lindisfarne. With the support of King Oswald, the monastery grew in prominence and became a center for a number of christian missionaries spreading christianity across England and Scotland.

St.Cuthbert Bishop of Lindisfarne

The monastery on Lindisfarne also held the remains of the very popular St. Cuthbert, who for a short time had been the bishop there. In his time Cuthbert had been renowned for his devotion and his abilities as a seer and healer. After his death in AD 687, many miracles were said to happen that were associated with the power of his remains. This made the monastery a place many sought as a pilgrimage, and it thus also received valuable gifts.

Filled with silver and gold ornaments and other relics, the monastery was really only protected by the christian God.

The Pagan Vikings Raid Lindisfarne

It was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as having happened in January of 793. However it is generally accepted as being a mistake by the scribe. The actual date of the raid is believed to be June 8th. 793. This really makes a lot more practical sense as well. No sane, or crazy, vikingr would set out for an ocean crossing in the middle of winter.

Early in the summer however, after having plowed their fields and prepared their ships, time was ripe for raiding. Before they started visiting the British isles, the Norwegian vikings would traditionally have gone on raids towards the east, into Sweden and the Baltics. In the 790’s however, they ventured west, starting what would become more than two hundred and fifty years of Viking raids, invasions and settlements across the British isles.

In June, at the height of summer in Scandinavia and England, the sun rises around 4AM and doesn’t settle until after 10PM. The days are long, the seas are usually calm, and in fair conditions it would only be a two or maybe three days sail from the west coast of Norway to the east coast of England. For the seafaring vikings, it was hardly an arduous journey.

The “First Raid” in Britain

The Lindisfarne raid is often touted as the “first” raid and beginning of the Viking Age in Britian. However, Norsemen from Norway and Denmark had reached, and raided along the coast of England for several years before Lindisfarne. Four years earlier, a group of vikings in three boats had landed on the southern England island of Portland. There they were raiding and pillaging, not leaving until after killing a reeve named Beaduheard and his men.

It was the significance of Lindifarne as a Christian center however which made the raid on it so noteworthy. In fact, the whole European Christian world was shocked afterwards. They were struggling to explain why God had failed to protect the monastery.

The Raid as Described at the Time (or some time after)

In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for what happened in 793, the raid on Lindisfarne is described. Interestingly it has some ominous forewarnings earlier in the year.

AD. 793. “This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January (this is understood to be a mistake, and is corrected to June 8th) in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by ransacking and slaughter.”

Another written source is the The Historia Regum (“History of the Kings”). Believed to have been written by Symeon of Durham in the 12th century also describes the raid. It is believed to have been based on a lost version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It is believed to be quite accurate, as its source was written closer in time to the actual events.

“In the same year [AD 793] the pagans from the northern regions came with a naval force to Britain like stinging hornets and spread on all sides like fearful wolves, robbed, tore and slaughtered not only beasts of burden, sheep and oxen, but even priests and deacons, and companies of monks and nuns. And they came to the church of Lindisfarne, laid everything waste with grievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted steps, dug up the altars and seized all the treasures of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers, took some away with them in fetters, many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults, some they drowned in the sea…”

How Could God Allow the Horror of the Raid to Happen

Struggling to understand why a group of pagans could have come across the ocean to raid one of the holiest sites in all of Christian Britain, there was enough blame to go around.

In a letter to King Ethelred of Northumbria, Alcuin, a prominent member at the court of the powerful King Charlemagne writes.

“Lo, it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold, the church of St. Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples.”

In another letter, Alcuin is writing to the new bishop of Lindisfarne.

“the calamity of your tribulation saddens me greatly every day, though I am absent; when the pagans desecrated the sanctuaries of God, and poured out the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope, trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the street…. What assurance is there for the churches of Britain, if St Cuthbert, with so great a number of saints, defends not its own? Either this is the beginning of greater tribulation, or else the sins of the inhabitants have called it upon them. Truly it has not happened by chance, but is a sign that it was well merited by someone. But now, you who are left, stand manfully, fight bravely, defend the camp of God.”

A Treasure That Was Saved From the Pagans

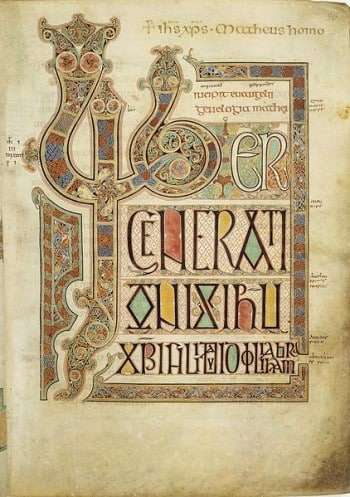

Arguably a greater treasure than silver or gold, is a manuscript known as the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Imagine being a Viking raider, arriving at the shores of Lindisfarne. Your eyes are set on treasure, but there’s this one item, that doesn’t quite catch your fancy. Why? Well, for starters, you can’t read Latin. This beautifully illuminated manuscript, a masterpiece of Hiberno-Saxon art, is essentially a book of religious texts. To the viking raiders, the intricate inscriptions and Christian symbolism mean little. It’s like finding a book in a language you don’t understand – sure, it looks pretty, but what value does it hold for you?

Crafted around 715–720, the gospels were not just any ordinary religious texts. They were a labor of love by Eadfrith, a monk who later became the Bishop of Lindisfarne. The manuscript was a tribute to St. Cuthbert, combining various artistic influences into a unique style.

The Vikings however were more interested in tangible wealth. High onb their list would be gold, silver, jewels – the kind of stuff you can show off back home. The Gospels’ original jeweled cover, made by Billfrith the Anchorite, was indeed lost during the raid, but the manuscript itself? It was left relatively unscathed.

So, the Lindisfarne Gospels, a gem among the monastery’s treasures, surviving the raid with just a damaged cover. Possibly a good insight into their different cultures. How they on one side valued writing, and on the other didn’t really have widespread writing at all. As such, the viking raiders overlooked what is now considered a priceless artifact. It wasn’t about the beauty or the craftsmanship; it was about the utility and immediate value.

Featured Image from Depositphotos