When diving into writing about the Helm of Awe, it’s important to point out a few things right from the beginning. There are many symbols closely related to Norse mythology. However, the symbol commonly known today as the Helm of Awe today is not one of them.

On the other hand, here is an Aegishjalmr (Old Norse for Helm of Awe) mentioned in the Poetic Edda and there is an interesting looking symbol from Iceland known as the Helm of Awe. The two are not necessarily the same though. Read on and I’ll explain. When approaching Norse mythology, it is best to keep an open mind, but also not buy into all the popular myths and lore.

Aegishjalmr: From Norse Roots to English Interpretation

The term ‘Aegishjalmr’ finds its roots in Old Norse. When we dissect the term, it breaks down into two distinct components: ‘Aegis’ and ‘Hjalmr’.

- Aegis: This segment of the word translates to ‘shield’. It represents protection and defense, a barrier against potential threats.

- Hjalmr: This part translates directly to ‘helm’ or ‘helmet’ in English. It further emphasizes the protective nature of the symbol, much like a physical helmet would shield against harm.

English Interpretations: Helm of Awe and Helm of Terror

The translation of ‘Aegishjalmr’ into English as ‘Helm of Awe’ or ‘Helm of Terror’ is rooted in the etymological components of the term:

- Helm: Directly derived from ‘Hjalmr’, this term has always been associated with protection in various Germanic languages. In English, a helm is a protective covering, especially one for the head, like a helmet. It signifies a barrier or shield against potential threats.

- Awe and Terror: The ‘Aegis’ component, while translating to ‘shield’, carries connotations of both awe and terror in its protective capacity. In Old Norse contexts, shields were not just passive protective items but were also symbols of a warrior’s might and presence on the battlefield. The choice between ‘awe’ and ‘terror’ in translation hinges on the context in which the Helm is referenced. ‘Awe’ suggests a reverence and respect for the power it represents, while ‘terror’ emphasizes its capacity to intimidate and ward off adversaries.

In a direct etymological translation, ‘Aegishjalmr’ would be rendered as ‘Shield-Helm’. However, the translations ‘Helm of Awe’ and ‘Helm of Terror’ attempt to capture the broader cultural and symbolic nuances associated with the term in Norse literature and beliefs.

Helm of Awe (Aegishjalmr) Background and Origins:

The origins of the Helm of Awe are deeply rooted within the ancient Poetic Edda poems in the so-called Niflung cycle. These poems cover the events surrounding the rise and fall of the Völsungs, and include the stories of the hero Sigurd Dragonslayer and the valkyrie Brynhild to name a few.

However, I need to point out that in the story of Sigurd and Fafnir, and the handful of mentions of the Helm of Awe, it is never explicitly explained what it is. It might be a helmet, or maybe a cloak of some kind, lastly it could be it’s not a physical object at all.

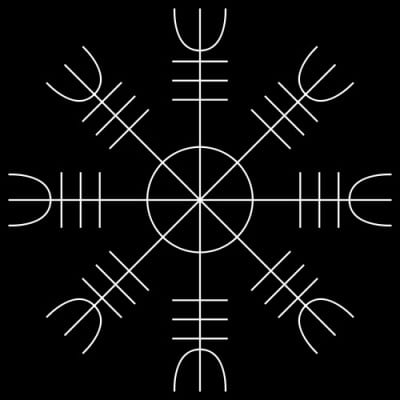

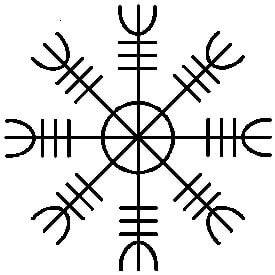

I point this out because today, most people have a clear picture of the Helm of Awe as this symbol below. However, this symbol is “modern” in this context. It can only be traced back to an Icelandic manuscript from the 16th century.

The myth of Sigurd, Fafnir and the Helm of Awe

The story of Sigurd and Fafnir and the Helm of Awe is nestled inside the collection of poems called ‘the Niflung cycle’ of the Poetic Edda. The poems make up the source for the ‘Saga of the Völsungs’, an epic saga written in the 13th century. These stories were likely created some time in the 9th and 10th century, or even before, but were only compiled as a collection in a book in the 13th century.

The story that leads to the Helm of Awe is found in the Reginsmál and Fáfnismál, early in the Niflung cycle. It starts with Loki killing an otter which turned out to be the transformed son of a dwarf caller Hreidmar. He, in turn, demands gold from Loki, Odin and Thor who are all traveling together as compensation for the lost son.

Loki manages to get the gold from a dwarf called Andvari, but he puts a curse on the gold which follows it into the future. Loki then gives the gold to Hreidmar and his two sons Regin and Fafnir.

Fafnir’s Transformation

Fafnir as you understand was not always the fearsome dragon we often picture. Originally, he was a dwarf, and son of the dwarf king Hreidmar. Then the family came into possession of this vast treasure, which included the cursed gold of Andvari. This treasure was cursed to bring doom to its possessor. Overcome by greed and the allure of the treasure, Fafnir murdered his father and took the treasure for himself. His insatiable greed transformed him into a monstrous dragon, a guardian of his ill-gotten wealth.

Sigurd’s Quest

Enter Sigurd, a legendary Norse hero. Guided by the wisdom of his mentor, Regin (who was, unbeknownst to Sigurd, Fafnir’s brother), Sigurd set out to slay the dragon and claim the treasure. Regin’s intentions were not pure; he sought revenge for their father’s death and desired the treasure for himself.

Fafnir and the Helm of Awe

As Sigurd and Fafnir’s paths crossed, a profound exchange took place. Before the fatal blow was dealt, Fafnir revealed to Sigurd the power of the Helm of Awe, attributing much of his invincibility to it. He recited:

“The Helm of Awe

I wore before the sons of men

In defense of my treasure;

Amongst all, I alone was strong,

I thought to myself,

For I found no power a match for my own.”

This revelation was not just a testament to the Helm’s power but also a reflection of Fafnir’s tragic flaw: his overwhelming pride and greed.

Aftermath and Reflection

Following their exchange, Sigurd slays Fafnir and, with Regin’s guidance, tastes the dragon’s blood. This act granted him the ability to understand the language of birds, who revealed Regin’s treacherous intentions. Sigurd, forewarned, killed Regin and claimed the treasure, including the cursed gold.

The saga of the Völsungs continues from there, but trust me when I say that in the end the treasure didn’t serve Sigurd well.

The Helm of Awe in the Poetic Edda

That story, with Sigurd slaying the dragon Fafnir and taking his treasure, the Helm of Awe as a part of it, is all that is mentioned of it in the Old Norse poems Reginsmál and Fáfnismál. Then the Völsunga saga was written later, based on these poems. In it, the Helm of Awe is mentioned several times, always as a physical thing, something Sigurd wore, like a helmet, and not as a symbol.

The story never delves into the real origins of the helm. It is only said to be part of the treasure of Andvari that Loki takes to pay off Hreidmar. Furthermore, there isn’t a very specific explanation to its powers. However, it clearly strikes people who see it with dread and awe, possibly incapacitating them.

While its exact powers are not specific, it is clearly something that granted whoever wore it great power in battle or any confrontation.

Origins of the Helm of Awe as a Symbol

The Helm of Awe I discussed above, which is mentioned in the Poetic Edda, was never described as the symbol people associate with it today. This symbol is first found in a book from the late 16th century. While this is certainly old, it is several hundred years after the end of the Viking Age. Incidentally, it is also closer to our own time than to that of the Vikings, but that doesn’t really prove anything.

Unknown to most people is the proliferate occult cultures that thrived on Iceland long into the 19th century. In some respects, it continues to thrive today, albeit not at quite the same rate as in earlier days.

Drawing on the rich history and symbolism of Norse mythology, magic, runes and galdr included, many more “modern” concepts and symbols seem to be rooted in the heritage of old. This is to say that books and symbols found in Iceland that “looks” like they are Old Norse aren’t necessarily that. One such item is a fascinating short book of magic, spells and stave symbols, likely from the late 16th century.

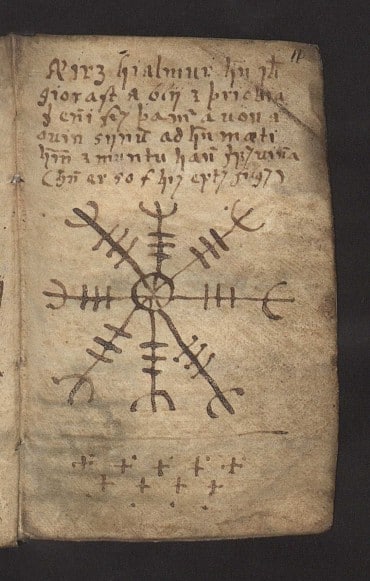

The Galdrabók (Book of Magic)

The Galdrabók, or “Book of Magic,” is a fascinating artifact from Iceland’s rich history of magical practices. This grimoire, dating back to the late 16th or early 17th century, is a compilation of spells and magical staves, reflecting a blend of Christian and pagan beliefs that were prevalent in Iceland during that period.

It contains a collection of 47 spells and various magical staves. These spells range from relatively benign purposes, such as finding lost objects or ensuring a good catch while fishing, to more aggressive intents, like causing harm to enemies or gaining power over others. The spells often invoke both Christian and pagan entities, showcasing the syncretic nature of Icelandic magic at the time.

Icelandic Magical Staves

Icelandic magical staves, or “galdrastafir,” are a significant part of the country’s magical tradition. These staves are symbols, often with intricate and abstract designs, believed to hold magical powers. They were used for various purposes, including protection, love, and prosperity. Some of the most famous staves include the Vegvísir, a symbol said to guide one through rough weather, and none other than the Aegishjalmr (Helm of Awe), a symbol of protection and power.

The instructions above the image reads:

“Terror Helm. It shall be made in lead, and when

a man expects his enemies he shall imprint it

on his forehead. And thou wilt conquer him.”

The Galdrabók and the magical staves it contains are not just historical curiosities. They offer a window into the mindset and beliefs of Icelanders during a time of significant cultural and religious transition. They reflect the struggles, hopes, and fears of a people living in a harsh and often unpredictable environment.

Modern Interest Pushing the “Old Norse” Connection

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the Galdrabók and Icelandic magical staves. This revival is part of a broader interest in pagan and folk traditions. The symbols have found their way into modern jewelry, tattoos, and artwork. Often they are emblems of heritage and connection to the mystical aspects of Icelandic culture.

In this revival however, some nuance has been lost. Obviously not all people will read up on how Iceland developed culturally from the Viking Age and up to today. However, there are many arguments for why its simply wrong to call the Helm of Awe, an Old Norse symbol.

There is no argument though that this symbol has deep roots in ancient Icelandic lore. However, there could be a connection between the symbol and the physical helmet of the Old Norse myths. Right now though, such a connection is an interesting possibility at best.

As such, presenting the Helm of Awe as an Old Norse symbol, with no caveats is just wrong. Could it be based on Old Norse lore and myths? Certainly! Would people from the Viking Age recognize the symbol most people today see as the Helm of Awe? That is doubtful, or possibly quite unlikely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Derived from Old Norse, ‘Aegis’ translates to ‘shield’ and ‘Hjalmr’ to ‘helm’, symbolizing protection.

Contrary to popular belief, the Helm of Awe from the Old Norse texts was a physical object, like a helmet. It was worn by both Fafnir and later Sigurd.

There really isn’t any evidence to support that. While from Iceland, the symbol can only trace its roots back a few hundred years, not to the Viking Age.

Featured Image Credit: No machine-readable author provided. Rumpenisse assumed (based on copyright claims)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons