Symbols played a significant role in the culture and Norse mythology . With no real boundaries between the gods, magic and their own world, symbols could be powerful. As you will see from the ones I am covering here, they were used in many different ways.

Before diving into discussing the symbols in this list I want to make a couple of points. Some of these symbols are fairly well understood or at least documented in old texts and artifacts. Others, less so, and remain both mysterious and harder to prove to be directly from the Vikings.

In saying that, my personal position is that it is important to keep an open mind when considering the origins and sources of these symbols. While some symbols are controversial because we are unsure of their true name, others might be less Viking Age than you probably believe.

Two good examples are the Vegvisir and the Valknut symbols. The former is really not associated with the Viking Age at all. The latter however is decidedly so but is named incorrectly.

The oldest descriptions of the Vegvisir are from a few manuscripts from the 19th century. When you are my age, that is the same century as my great grandparents. While it’s old, they were definitely not Vikingr. As an example, the first steam engine train is older then the Vegvisir symbol, at least as fas as it can be documented. Steam engine trains are not from the Viking Age.

As for the Valknut, there seems to me to be a straightforward case for why the name is wrong, but the symbol is truly Viking Age.

Most well-known Viking symbols

The Vikings had a strong oral culture where literacy rates were likely quite low. Instead of written stories, they had a rich storytelling tradition. They also didn’t necessarily have a clear distinction between what was “real” and what was based on belief in something we would call supernatural.

The gods walked among them and could be invoked for help, evil spirits had to be placated, your fate was predestined and magic was all around. In this culture, symbols held a special place and were used for all manner of things. Scaring your enemy, protecting from evil, or putting an adversary to sleep.

Here we will dive into some of the most well-known and iconic symbols of Norse mythology, including runes, the Helm of Awe, the Horns of Odin, the Vegvisir, the Sun wheel, Mjöllnir, the Svefnthorn, and the Valknut.

I. Runes

Yes, the runes were the Vikings alphabet, but they could also be magical and used for all manner of things. Their use spans from inscriptions on small objects and talismans to carvings on runestones and other large objects and recording laws and historical events. They were also used for divination and as a means of casting spells.

There are several different systems of runes, but the most well-known are the Elder Futhark and Younger Futhark, which consist of 24 and 16 runes respectively. The Elder Futhark was replaced by the Younger Futhark around the late 8th century. This process likely took decades or even a century and went on long into the Viking Age.

As with almost everything Old Norse, opinions are varied when it comes to runes as symbols. While some will say that they were more or less only an alphabet, I feel that is overly simplistic.

The word “rune” itself means “secret” or “mystery,” and the runes were often used for divination and magical purposes.

How Odin discovered the runes

In the poem Hávamál from the Poetic Edda we learn how Odin hung himself on Yggdrasil to discover the runes.

Stanza 138:

I know that I hung on the wind-tossed tree

for nine long nights

wounded by a spear, given to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no one knows

from what roots it rises.

Stanza 139:

No bread was offered me,

nor a horn.

I peered down,

I took up the runes.

Screaming I took them.

Falling back down again.

Odins’ willingness to suffer so greatly for unlocking the mystery of the runes should give anyone pause to reflect. Why were they so important, if not for their perceived magical abilities? Stating that they are simply alphabets seems to me uninspired.

There are a number of examples, also from the Eddas and Sagas of rune spells being inscribed onto artifacts. With the magical inscription that object would have powers of healing or warding off evil for example.

A special form of runes called bind runes, where two, or sometimes three, runes are combined also show how runes were seen as more than mere letters. By combining two runes the meaning and symbolism of the resulting bind rune would seemingly become more powerful.

An example of this that you see every day is the Bluetooth logo. Named after the Viking Age king of Denmark and Norway Harald “Bluetooth” Gormsson. The sign is a combination of the Younger Futhark runic letters H and B. Combined they make the Bluetooth logo known all over the world today.

II. Helm of Awe (Aegishjálmr)

The Helm of Awe is found mentioned in the ancient Poetic Edda poems Fáfnismál and Reginsmál. However, in these Oln Norse poems, the Aegishjalmr is something (possibly a helmet) worn by the drasgon Fafnir, then later by the hero Sigurd.

Today, most people associate the Helm of Awe with a symbol. Furthermore, many also boldly claim that this is a powerful symbol from Norse mythology, said to be representing protection, strength, and courage. However, there sadly is no evidence to substantiate a claim that the Helm of Awe of the Poetic Edda, ever was a symbol, or that it would look like the symbol above.

In the Poetic Edda, for example, in the Lay of Fafnir, the Helm of Awe is described. This translation is adapted by me from a 1936 publication by Henry Adams Bellows in the public domain:

The Lay of Fafnir (Fáfnismál)

Stanza 16

Fafnir spoke:

- “The Helm of Awe I wore | to frighten mankind,

While I lay guarding my gold;

I seemed mightier | than any man,

For someone fiercer I never found.”

The Norse Roots of the Symbol

The symbol that is recognized as the Helm of Awe however, has its roots in the 16th or 17th century. This is centuries after the end of the Viking Age, and Iceland was more or less Christian at this time. While there is a lack of actual evidence tying the symbol together with the concept from Old Norse myths, thast doesn’t actually mean there never were such evidence. I go into this, and the real origins of the Helm of Awe in another blog post.

Description

The eight arms of the symbol could be seen as representations of the eight legs of Odin’s horse, Sleipnir. Each of the arms points are strikingly similar to runes from both the Younger- and Elder Futhark.

Elder Futhark Z rune Algiz (Elk) represents protection, security and guidance of higher powers. Younger Futhark M rune Maðr (Man) represents man, but also ability and mortality.

The lines going across each of the arms could be the Isa (Ice) rune, from both the Elder- and Younger Futhark. While it translates as Ice, it also represents stillness and isolation.

Seen together it is easy to understand how this symbol was seen as a protective symbol, but exactly for who, in what time is more unclear.

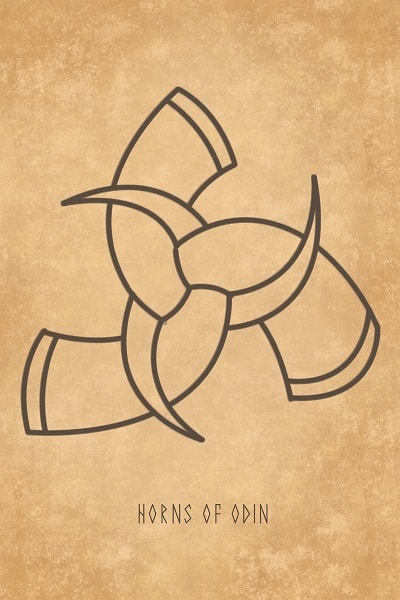

III. Horns of Odin

The Horns of Odin is a prominent symbol in Norse mythology. The Horns of Odin are depicted as a set of three interlocking horns and are often associated with the god Odin. The symbol is known from a variety of sources, including Viking Age artifacts and Old Norse literature.

The origins of the Horns of Odin symbol are somewhat unclear, but it is thought to be connected to the Mead of Poetry. The tale from the Prose Edda, tells of how Odin pursued the so-called Mead of Poetry. The mead was made from the blood of Kvasir and held magical powers.

Kvasir himself was made by all the gods at their peace agreement after the Aesir-Vanir war. He was believed to be the wisest of all beings, able to answer any question, and also the best poet. Some particularly evil dwarves killed poor Kvasir for his blood. Mixing it with honey, they created the magical mead and stored it in three vessels.

Through some light deceit, Odin was able to secure the mead for himself. A few drops he spilled fell onto Midgard, blessing anyone who was touched by them with fabulous poetic abilities.

Description and meaning

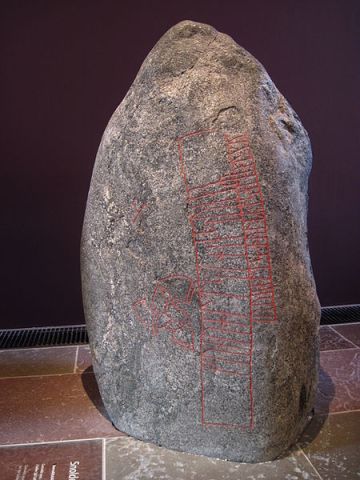

The three interlocking horns appear in several finds. One of which is a 9th-century rune stone from Denmark called the Snoldelev stone.

The horns design is heavy with symbolism. There are three horns, a number that along with the number nine is important in Norse mythology. Some examples are the three roots of the world tree Yggdrasil, the three Norns, Loki has three children that will bring forth Ragnarök and as a last example, in the creation myth there are three first beings; the jötun Ymir, the cow Audhumbla and the god Búri.

As for the horns being ale horns that also lends itself to symbolizing much more than merely being vessels for drinking. Odin the All-Father is said to be the god of alcohol/mead, and he lives on it alone. As discussed above the mead of poetry was a source of infinite wisdom, which Odin pursued at all costs.

While it is easy to read into the symbolism, the origins of the design are probably inspired by other symbols. Symbols of the intertwined circles or half-moons appear in several cultures. One near to the Vikings is the Irish tri-spiral symbol found in Newgrange.

Dated to around 2600-2500 BC the spirals must have made an impression on the first Vikings to ever see them. The origins and inspiration for the Horns of Odin are probably a combination of many influences, but this could surely be one.

IV. Sun wheel or Swastika

The Sun wheel (Old Norse Sólarhvél) also known as the solar cross or as the swastika is a symbol that has been used by a variety of cultures throughout history. Typically seen to represent the sun and the cycle of life. Sadly appropriated by the Nazis around the middle of the 20th century, it is a much older symbol.

From Viking Age finds, the round sun wheel and the more angled swastika seem to be used interchangeably. The symbol has been found on a number of artifacts from large rune stones to small amulets. An example is the Snoldelev stone from Denmark mentioned above.

In the old Icelandic Galdrabók, a book on magic and spells from around 1550-1600, the sun wheel or swastika is mentioned as well. Interestingly it is referred to as “Thorshamar”, ie. Thor’s hammer. This is supported by mentions of Thor’s hammer symbol in a few of the sagas described as a circle with a cross.

It is also commonly seen in Ireland and Scotland, then known as the Celtic cross. Predating Christianity by hundreds, if not a thousand years. Used in the worship of the sun, it was later adopted as a cross of Odin or Odin’s wheel.

Description and meaning

The sun wheel is typically depicted as a circle with four or eight arms radiating outward. In the Celtic cross versions, the arms with distinct points go out past the circle in the middle. The arms of the sun wheel may be straight or curved, and the symbol may be decorated with various designs and patterns.

It is the version with straight arms that forms the symbol most commonly referred to today as the swastika. Interestingly that design is very common in for example Buddhism as well as other religions.

While the meaning is somewhat obscured through a multitude of uses, there are some points most scholars seem to agree upon. With its connection to the god Thor, inscribing it to amulets, hammers or other artifacts should bring protection or luck. Being the protector of the common man, having something bearing Thor’s sign was surely a good luck omen.

In connection to Odin it might be seen as symbolizing the circle of life, turning from birth to death, or the cyclical wheel of time through a year.

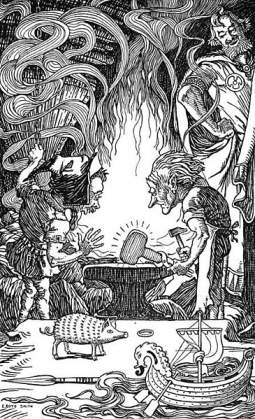

V. Mjollnir (Old Norse Mjǫllnir)

Thor’s hammer Mjollnir is one of the most iconic symbols of Norse mythology, or maybe any mythology. Mjöllnir is a powerful weapon capable of shattering mountains and crushing giants. Created by master craftsmen, the dwarves Brokkr and Eitri, Mjollnir has no equal.

So powerful in fact is Mjollnir that Thor has a set of special gloves he wears to handle the hammer. They are called the Járngreipr (Iron Grippers) and together with his belt, the Megingjörð (Power Belt) they make Thor invincible. That is until Thor meets Jormungandr for their destined battle at Ragnarök and finally loses his life to the serpent.

In the highly entertaining story of how the dwarf brothers Brokkr and Eitri made Mjollnir, we get some insight into the creation. According to legend, the brothers were disturbed by Loki when forging it and as a result, the handle was short.

Like a boomerang, the hammer will return when it has been thrown and it has other magical powers as well. While out on journeys (to fight the jötnar) Thor actually often eats his own goats. The next morning Thor waves his hammer over the pile of bones and hides and the goats spring to life.

Description and meaning

vector by Depositphotos

The Mjöllnir has been found innumerable times as small pendants Vikings would have worn around their neck. I have read somewhere that this became increasingly popular as a response to Christians wearing crosses. Personally, I’m not so sure the Vikings didn’t just wear it for good luck, strength and protection on their own accord though.

Being a people surrounded by talismans, spells and the otherworldly, carrying Thor’s hammer seems like a good idea. Thor was likely a far more popular god than Odin among the common Vikings and invoking his help was widespread.

Be it for courage and strength in battle or protection from any kind of evil, many a Viking wore one. As a protector of man, Thors’ hammer was popularly used for blessing marriage and childbirth alike.

In the world of the pragmatic Vikings, the old gods lived long after the Christianization of Scandinavia. Believing in a Christian god didn’t necessarily mean they gave up completely on their old gods. One interesting example was found in Denmark. There an enterprising smith had a mold to make both a cross and a hammer, covering both religions.

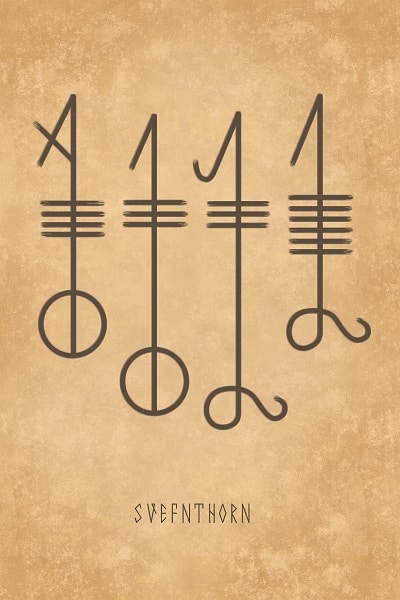

VI. Svefnthorn

The Svefnthorn (Old Norse Svefnþorn), also known as the “Sleep Thorn,” is a symbol found in Old Norse mythology and literature. It is believed to have the power to put people into a deep sleep. The Svefnthorn is used several times in the old sagas, but how it is used and the effect it has is less than consistent.

It’s worth appreciating that what might seem contradictory to a modern reader, might have made perfect sense long ago. When having access to all the sagas and poems at your fingertips it is easy to compare and pass judgment. Back in the Viking Age though, the stories were more fluid, passed down orally through hundreds of years, across great distances.

With regards to the Svefnthorn, that seems to also be the case. As we’ll see in the examples below, the use and its effect could vary. Maybe it was as simple as the effect being however long the one who used it wanted it to be?

There are three accounts of the Svefnthorn in use in the old sagas. Across all three the way it is used and the effects are quite different.

The Völsunga Saga

In the well-known Völsunga saga, the valkyrie Brynhild angers Odin and has to pay a harsh price. When she chooses another to be victorious in a battle than Odin wanted he is enraged.

As punishment, Brynhild is cast out of the valkyries and, using a svefnthorn, Odin puts her into a deep sleep. Brynhild will later be woken from her deep sleep by the hero Sigurd, but that is a story for another day (read post).

In this instance, Odin doesn’t use a symbol but pricks her with the svefnthorn, so it is decidedly a physical thing.

Saga of King Rolf Kraki

Once upon a time, two brothers shared being king of Denmark. They were Hroar and Helgi, the first may be more thoughtful than the latter. Helgi went traveling all across their kingdom to have local chieftains swear their allegiance.

After some time he and his men came to the island of Als. The island was ruled by Olof Sigmundsdottir, Als-Queen. Having been brought up much like the son the old king had never gotten, Olof was unlike most other women of the time.

Often carrying weapons and chainmail, Olof was a warrior queen, and Helgi quickly was smitten. Seeing her as rather easy prey, Helgi “proposed”, or declared they should get married that first night.

As the evening wore on, Helgi and his merry men had more than enough to drink. Late in the evening, expecting to close the deal on his new marriage, Helgi fell asleep in Olof’s bed. Deciding to put Helgi in his place, Olof stuck Helgi with a svefnthorn ensuring he would sleep through anything.

With the aid of some of her men, Olof saw to it that they cut all of Helgi’s hair off. Next, they smeared him with tar and put him in a large leather sack along with a great many rags.

Leaving the sack with Helgi lying on the beach, they roused his men the next morning and sent them to the ship. Finding the sack, and Helgi, he only wakes up after the svefnthorn accidentally falls out.

Göngu-Hrólfs saga

In this tale of deceit, trickery and adventure we meet up with Hrolf and follow him on his adventures. To say that Hrolf leads an interesting life is an understatement.

On one of his adventures, he meets a man called Vilhjalm who asks to be Hrolf’s servant. Soon after this, Vilhjalm, using a svefnthorn, manages to trick Hrolf into swearing to be Vilhjalms servant and telling anyone that Vilhjalm is his master.

This lie leads down a road of more lies and in the end the two come to a violent clash where Vilhjalm cuts off both of Hrolfs legs. True to the abilities of the mighty dwarven craftsmen, Hrolf has his legs restored by an evil dwarf named Mondul.

In the end, Vilhjalm is killed for his treachery and Hrolf gets his girl and becomes ruler of Russia or the part of Russia the Vikings knew.

The Huld Manuscript

In addition to being mentioned in several sagas, the svefnthorn symbol is actually documented in the Icelandic Huld manuscript. The Icelandic manuscript called “Huld,” likely named after the Icelandic word “hulda” meaning secrecy, was created by Geir Vigfússon in 1860.

It is one of many manuscripts from the late 18th to early 20th centuries that contains collections of runic alphabets and/or magic symbols and sigils used in earlier times. “Huld” stands out for its artistic presentation and skilled handwriting. The manuscript has 27 leaves, each with writing and drawings on both sides.

The pages are numbered up to 60, but the sequence is interrupted in the middle by what is likely to have been blank pages that were removed. The first half of the manuscript includes a list of 329 runic alphabets, some of which are recognizable and others very cryptic.

The second half includes a smaller set of 30 “stafir,” an Icelandic word meaning characters or staves, which are symbols, sigils, insignia, and bindrunes (strings of runic symbols) along with Icelandic and cryptically coded text providing titles, descriptions, and instructions for each one. These symbols are currently referred to as “galdrastafir,” with “galdur” meaning magic in Icelandic.

Some scholars and other experts seem quick to disregard the Huld manuscript and others from the 19th century because of their relatively young age. Personally, I feel this is unwarranted and a large disservice to these rich and well-preserved sources.

In light of how Christians set about eradicating anything “pagan” and even killing “witches”, it shouldn’t be surprising that few manuscripts have survived. Thankfully a few people set out to collect this old knowledge sometime after the Reformation period. Over that time of a couple of hundred years tens of thousands of people were killed for “witchcraft” across Europe.

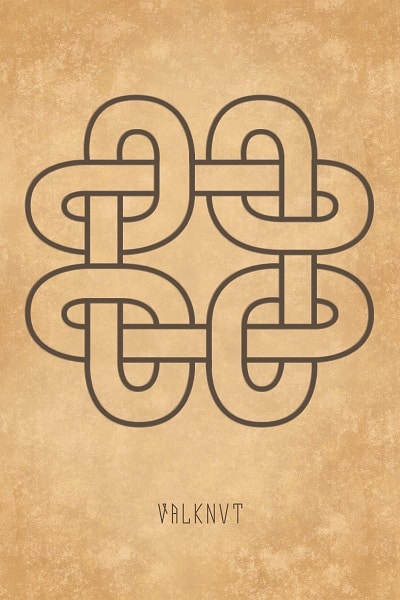

VII. (The real) Valknut

The so-called Valknut is among the most popular Old Norse symbols today, but it is also wrapped in controversy. There is no arguing that the symbol with three interlocking triangles is a genuine and powerful Norse symbol. However, it was certainly not known as the Valknut.

Actual Valknut symbol

In Norway, and across most of Scandinavia today, the Valknut ⌘ is a square with twisted loops at each corner. In English and in the world of knots, it is known as a Bowen knot. If you have an Apple computer, look down on your keyboard.

Actual find of Viking Age belt buckle from Onsøy (Odins Island) in Norway.

Going back to the triple triangle symbol, it is the real thing. It is well documented and has been found on finds all across the Nordics and the UK even. The Valknut name however seems to have been added to it much later, possibly in the last few decades.

Interestingly enough, the Bowen knot / Unnamed symbol is also an Old Norse symbol. One that hasn’t seen as much interest as the wrongly named Valknut.

There are a few theories of what the Triple-Triangle symbol might have been named, or even symbolized. While there are no instances where the symbol and a name appear together, there is strong evidence for an actual name.

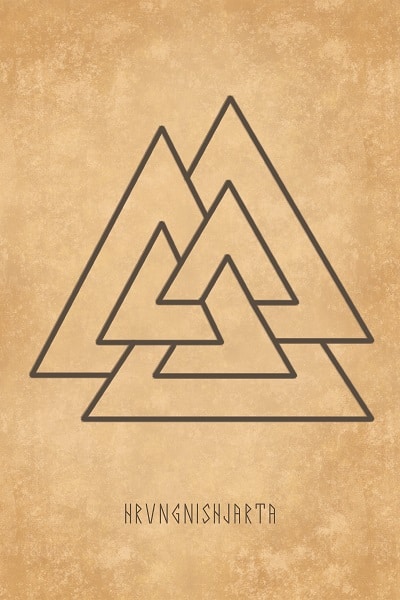

VIII. Hrungnir’s Heart

There are several interesting arguments that have been made about the Triple-Triangle symbol actually being a symbol for Hrungnir’s heart.

Hrungninr was the stone jötun who challenged Thor to a duel to death. This was after Hrungnir had behaved poorly as a guest in Valhalla, but had left his weapons at home. Snorri tells of the duel in Skáldskaparmál from the Prose Edda.

A special point is made about Hrungnir’s heart and how even when he faced Thor it did not falter. It goes on to describe the heart and even points out that it is the name for the carved symbol.

Skáldskaparmál ch. 17

“Hrungnir had a heart that is renowned, made of solid stone and spiky with three points just like the symbol for carving called Hrungnir’s heart has ever since been made.”

Translation by Anthony Faulkes, Professor of Old Icelandic at the University of Birmingham.

So, we have a symbol that is well documented and has been found numerous times, but the name is unknown.

Then we have the description of a symbol that was commonly used, which has three spiky points and is called Hrungnir’s heart.

Personally, I have a hard time understanding why anyone ever started calling the Hrungnir’s heart symbol the Valknut. Even through the fog of a thousand years, connecting the symbol known as the Valknut with the name given for something remarkably similar in the Prose Edda seems obvious.

Hrungnir’s heart meaning

While the meaning of the Hrungnir’s heart symbol is not understood fully, there are some indications as to what it might be associated with.

It is often associated with Odin and is thought to possibly represent the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. It might be used as a talisman to invoke the protection and guidance of Odin and is also associated with the idea of honor and bravery in battle. This last point is easy to connect with how Hrungnir stood his ground, actually standing on his shield which was lying on the ground when facing Thor. The mighty jötun, the strongest of his kin, was maybe dumb, but still brave.

The symbol has been found on several artifacts connected with death as well, possibly being connected with the journey after death.

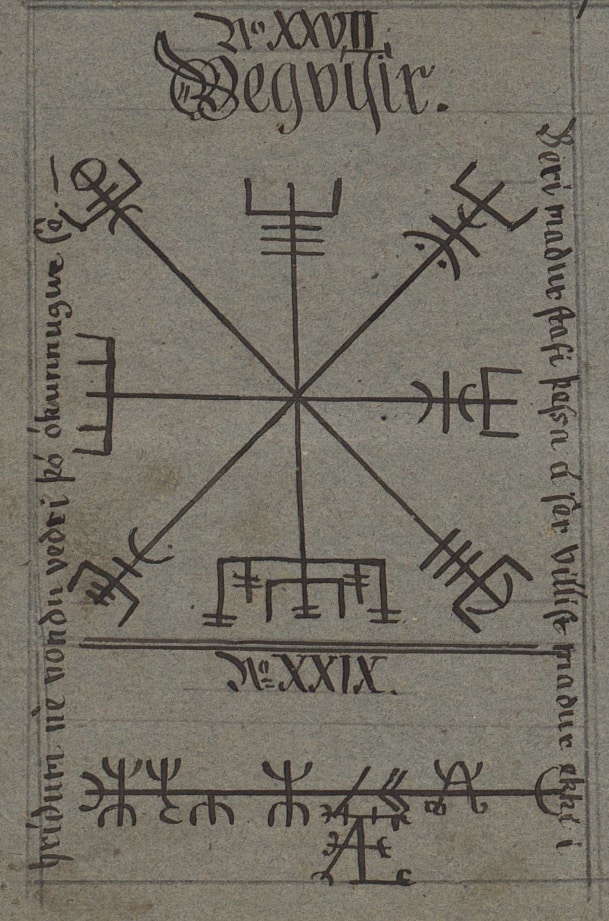

IX. Vegvisir

Possibly the most popular of all Old Norse symbols, the Vegvisir is another symbol clouded in mystery or even controversy.

Description and meaning

Anyone with even just a passing interest in Old Norse symbols or mythology has likely seen the Vegvisir. Sometimes called a “Viking compass” or “Pathfinder” its design has eight arms, each with a distinct point. The points are seemingly based on bind runes and if so, they can likely be traced back to the Elder Futhark.

The oldest known description and drawing of it is found in the Huld manuscript. It is numbered 27 and is found on page 60 of the book. As some pages from the middle are missing it can be seen here on page 26v

Origins Controversy of the Vegvisir

While the design of the Vegvisir is easy to connect with bind runes there are no mentions of it in any of the really old sources. This lack of concrete evidence from the oldest manuscripts (10th, 11th or 12th centuries), is why most scholars agree it is not actually from the Viking Age at all.

The Vegvisir is not mentioned or shown in any manuscript, on a rune stone or on any other artifact until it was described in an Icelandic manuscript from 1860.

The manuscript called “Huld,” likely named after the Icelandic word “hulda” meaning secrecy, was created by Geir Vigfússon in 1860. It is one of many manuscripts from the late 18th to early 20th centuries that contains collections of runic alphabets and/or magic symbols and sigils used in earlier times.

The manuscript has 27 leaves, each with writing and drawings on both sides. The first half of the manuscript includes a list of 329 runic alphabets, some of which are recognizable and others very cryptic.

The second half includes a smaller set of 30 “stafir,” an Icelandic word meaning characters or staves, which are symbols, sigils, insignia, and bindrunes (strings of runic symbols) along with Icelandic and cryptically coded text providing titles, descriptions, and instructions for each one. These symbols are currently referred to as “galdrastafir,” with “galdur” meaning magic in Icelandic.

While the Vegvisir has a really cool design and is evocative of what we today “feel” is Viking Age, it is most likely only a few hundred years old.

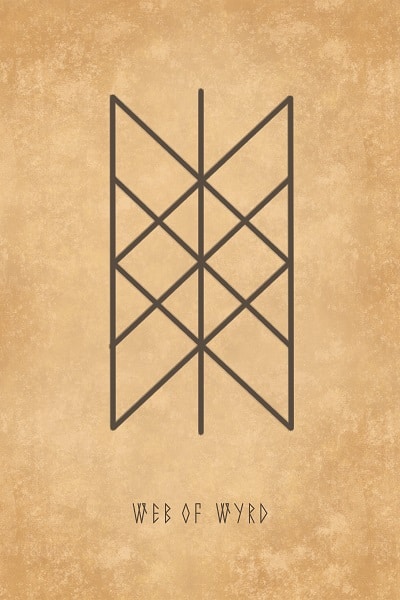

X. Web of Wyrd

The Web of Wyrd is the modern name, and symbol, for an ancient Viking Age concept. For both humans and the gods, their fates are predestined. Be it by the Norns, or in the case of the gods, maybe by the cosmos itself. A visualization of this used several times in the ancient texts is that of a web woven by the Norns.

Based on this ancient concept a symbol and name, “The Web of Wyrd” has become increasingly popular over the years. To be clear, the symbol is a modern design, even though being based on the design of runes. The same goes for the name of the concept itself, The Web of Wyrd is not referenced anywhere in the Eddas’ or sagas.

Origins of the name

As mentioned already, the visual image of mens fates being woven is one used many times in the sagas. What they, the Norns or even one time the Valkyries, are weaving has been called a web. As such the “Web” part of the name is easy.

As for “Wyrd” it is an Old English translation of the Old Norse name of the Norne Urðr, meaning fate. The symbol is also sometimes called “Skuld’s Net”, from the name of one of the other Norns, but it is less used.